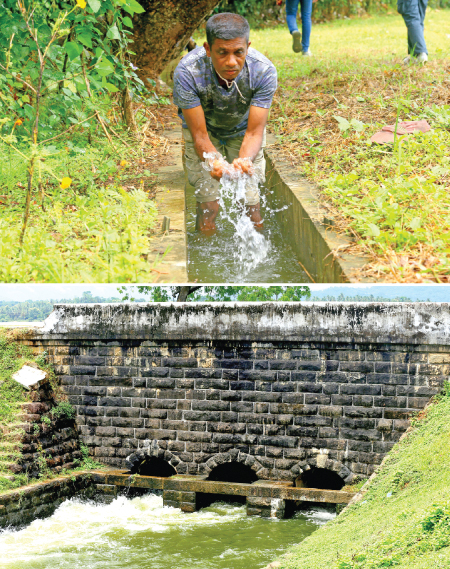

In the aftermath of Sri Lanka’s most severe economic downturn in recent memory, a beacon of revival is emerging through a bold and expansive initiative, the Integrated Watershed and Water Resources Management Project (IWWRMP). Funded by the World Bank and executed under the guidance of the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Lands and Irrigation, and in consultation with the Mahaweli Authority and local State institutions, this project is rejuvenating rural communities by reviving critical irrigation infrastructure across the nation.

The economic crisis of 2022 brought devastating consequences, particularly to the nation’s farming communities. Plummeting incomes, fuel shortages, abandoned lands, and food insecurity swept across rural areas. In response, the IWWRMP allocated US $10 million directly to community based organisations (CBOs), enabling them to rehabilitate small and medium-scale irrigation systems which were crucial to food production and livelihoods.

Beyond this emergency support, the larger vision of the project encompasses over Rs. 5.2 billion in irrigation infrastructure investments through 778 rehabilitation works across 25 districts. As of early 2025, 760 of these have been completed, directly benefitting over 150,000 farming families and revitalising more than 50,000 hectares of agricultural land.

From crisis to cultivation

One of the most immediate impacts of the project has been seen in regions such as Muhanthankulam in the Mannar District. Here, the FC 31 canal was rehabilitated at a cost of Rs. 3.4 million, restoring water access to 50 acres of previously abandoned farmland.

The effort, led by the local farmer organisation, allowed member families to resume cultivation, doubling their household incomes.

“During the crisis, I couldn’t even afford the lease payments on my farming equipment,” said Kanapathipillai Balakrisnan, a rice farmer and father of three. “After the canal rehabilitation, my income rose from Rs. 30,000 to over Rs. 100,000 per month. We’re no longer surviving. We are living.”

Similar stories emerged from across the country. In Vavuniya, the rehabilitation of the Muhanthankulam Main Canal and several tank bunds in Badulla, Anuradhapura, and Matale ensured stable irrigation and reduced water loss, preventing further abandonment of agricultural land.

Similar stories emerged from across the country. In Vavuniya, the rehabilitation of the Muhanthankulam Main Canal and several tank bunds in Badulla, Anuradhapura, and Matale ensured stable irrigation and reduced water loss, preventing further abandonment of agricultural land.

With projects ranging from minor canal desilting to major dam repairs, the IWWRMP has adopted a multi-agency execution model. The Irrigation Department, Mahaweli Authority of Sri Lanka (MASL), and Northern and Eastern Provincial Councils each undertook region-specific responsibilities.

A highlight was the use of advanced engineering techniques such as soil-cement-bentonite walls, wave erosion controls, and solar-powered sprinkler systems.Promising innovations that ensure both resilience and sustainability. For instance, structural improvements to the Walawa and Kalawewa main canals, and restoration of critical tanks such as Dewahuwa and Mahalindawewa, enhanced irrigation coverage without compromising environmental safety.

Investing in knowledge and youth

Beyond physical infrastructure, the project emphasised human capacity building. Over 800 young engineers and technical officers received on-the-job training through site supervision, quality control, and stakeholder engagement. Learning visits were organised at sites such as the Kalawewa and Bathalagoda schemes, providing first-hand exposure to modern water management.

Stakeholder forums at the Institute of Engineers, Sri Lanka, and regional administrative centres attracted over 500 participants. These sessions fostered cross-agency learning and created momentum for institutional improvements in dam safety, water monitoring, and climate adaptation.

Every district, from Kilinochchi to Matara, witnessed transformation. In Polonnaruwa alone, 88 schemes were restored with an allocation exceeding Rs. 320 million. Moneragala followed closely with 77 works valued at over Rs. 283 million. Even smaller districts such as Kegalle and Kalutara were not left out, receiving targeted interventions to secure the livelihoods of marginalised farmer communities.

The project touched all nine provinces, reaffirming the government’s commitment to inclusive, decentralised development.

What set the IWWRMP apart was its grassroots approach. Community contracting enabled local farmer organisations to take ownership of their schemes. They identified issues, submitted proposals, monitored progress, and even handled basic financial management.

This participatory model not only accelerated delivery but also enhanced transparency and accountability. In districts such as Trincomalee and Ampara, where historical neglect had left communities disenfranchised, such inclusive engagement has rebuilt trust in public systems.

Challenges and the road ahead

While physical progress has been commendable, financial disbursement in some schemes remains behind schedule. Climate variability, especially erratic rainfall and flooding, also poses a constant threat. However, with plans underway to digitise irrigation asset databases and strengthen dam monitoring systems, long-term sustainability is within reach.

The second phase of the IWWRMP, currently in design, aims to address larger infrastructure gaps while introducing institutional reforms in water governance.

It seems that the IWWRMP has done more than just restore canals and tanks; it has managed to restore dignity, hope, and opportunity for thousands of rural Sri Lankans. As the nation continues to navigate economic recovery, such projects offer a blueprint for inclusive and resilient development. They show that with the right investment, even the most vulnerable communities can become agents of transformation. BSP