The long-standing and controversial Chemmani mass grave case was taken up at the Jaffna Magistrate’s Court on July 15. This Incident, which dates back to the late 1990s, is once again under scrutiny due to recent excavation findings and renewed public attention.

The long-standing and controversial Chemmani mass grave case was taken up at the Jaffna Magistrate’s Court on July 15. This Incident, which dates back to the late 1990s, is once again under scrutiny due to recent excavation findings and renewed public attention.

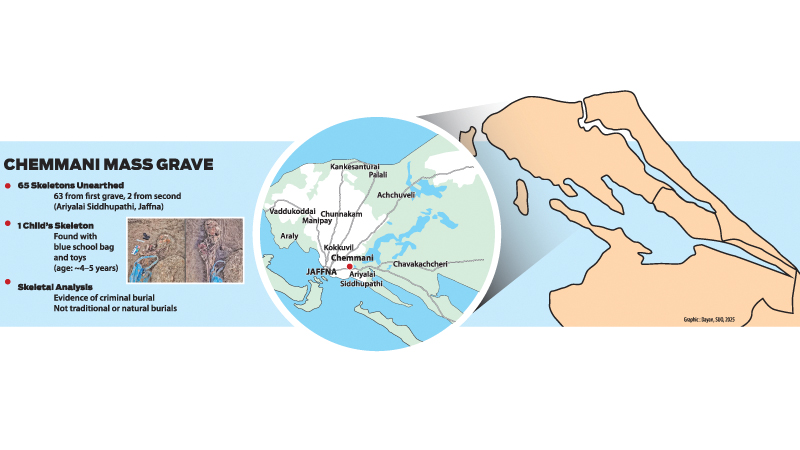

Forensic Archaeologist Prof. Raj Somadeva presented an interim report to the court highlighting three key observations from the ongoing excavation: the site bears clear evidence of criminal activity, indicating that the remains do not belong to natural or traditional burials; the skeletal remains differ significantly from those typically found in conventional burial contexts, raising serious concerns about the circumstances surrounding their deaths; and there is a pressing need for further investigation to uncover the full extent and nature of the findings.

Forensic Medical Officer Dr. Pranavan Pranavan Selliah presented a separate interim report on July 16. One skeleton was found with a blue school bag, accompanied by what appeared to be children’s toys. Dr. Selliah has said that the remains are likely those of a girl aged around four to five years.

The second phase of excavation work at the Chemmani site, which had been temporarily suspended, is scheduled to resume tomorrow. So far, investigators have uncovered 65 skeletons, 63 of which are from the first grave at the Siddhupathi Hindu cemetery in Ariyalai, and two from a second grave discovered during subsequent excavations. The next hearing in the Chemmani mass grave case is scheduled for August 6.

The second phase of excavation work at the Chemmani site, which had been temporarily suspended, is scheduled to resume tomorrow. So far, investigators have uncovered 65 skeletons, 63 of which are from the first grave at the Siddhupathi Hindu cemetery in Ariyalai, and two from a second grave discovered during subsequent excavations. The next hearing in the Chemmani mass grave case is scheduled for August 6.

On July 17, civil society organisations and human rights activists from Southern Sri Lanka gathered in front of the Colombo Fort Railway station to stage a protest, demanding justice for the victims of the Chemmani mass grave as well as other mass graves discovered across the country.

A diverse range of perspectives

To better understand the motivations behind the protest and the broader demands of those involved, the Sunday Observer spoke to several participants. They were asked two key questions: What kind of justice do you expect in relation to the Chemmani mass grave? And what kind of societal or political changes do you believe can be achieved through protests like this? Their responses revealed a diverse range of perspectives—some deeply personal, others overtly political—reflecting the pain, urgency, and continued hope that sustain and drive such Movements.

A youth activist from the Frontline Socialist Party,Lahiru Weerasekara, (FSP) said that while it is believed that many killings took place in the North during the war they have often been justified under the pretext of national security. “But the truth is, justice has never been served for these crimes,” he said.

The current Government, like many before it, made promises, especially when campaigning in the North, that it would address war crimes, land issues, and enforced disappearances. According to him people, however, appear to have little faith that those promises will be kept due to past experiences.

“Justice is not just about excavating a grave and counting bodies. It’s about accountability. The question is can we expect them to deliver justice for the countless people who were killed in the North? That’s why protests like this are necessary,” he said.

A member of the Executive Committee of the Ceylon Teachers’ Union, S. Muganeswari, who also took part in the protest expressed her deep anguish. “What is particularly heartbreaking about the Chemmani mass grave is that among the victims were students, innocent children who had no role in war or political conflict. As a teacher, I cannot remain silent when even my students are not spared. I felt a profound moral responsibility to speak out against this injustice. That is why I joined this protest, not just as a union member, but as an educator and as a fellow human being.” she said.

A member of the Executive Committee of the Ceylon Teachers’ Union, S. Muganeswari, who also took part in the protest expressed her deep anguish. “What is particularly heartbreaking about the Chemmani mass grave is that among the victims were students, innocent children who had no role in war or political conflict. As a teacher, I cannot remain silent when even my students are not spared. I felt a profound moral responsibility to speak out against this injustice. That is why I joined this protest, not just as a union member, but as an educator and as a fellow human being.” she said.

The President of the Ceylon Teachers’ Union, Joseph Stalin, questioned if there was in fact a political will to deliver justice.

“There are more than 22 mass graves identified across Sri Lanka. Every one of them demands justice. In the case of the Chemmani site currently before the courts, it’s been revealed that 65 people, including children, were found buried, highlighting the scale and horror of these crimes,” he said.

However according to him, it was concerning that it appeared the authorities were hesitant to grant the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights access to visit the site.

“That’s why public pressure is critical. Protests like the one we held in Colombo are essential tools to hold the Government accountable and pushing for truth and justice.” he said.

A member of the Social Scientists’ Association of Sri Lanka and co-editor of Polity magazine, Balasingham Skanthakumar who was also present at the protest highlighted its importance despite the low turnout.

“Some may ask why we protest even when only a few of us turn up. The answer is simple. Protesting in public spaces is not only about who sees us, it’s also about what it means for us. When we’re frustrated, angry, and upset by the injustices we witness, shouting at a television, or a phone screen, or throwing down a newspaper just isn’t enough. Coming together in protest gives us a sense of collective strength and solidarity. It reminds us that we’re not alone,” he said.

“By being out in public, we also send a message to those who pass us by, whether they’re on buses, bicycles, or just walking by. Maybe they’ve heard about these injustices, maybe they’ve seen something in the news, but never stopped to think about it. Seeing people protest, no matter how small the group, might make them pause, even for a moment. That pause can be the beginning of awareness,” he said.

Recalling the Aragalaya Movement, he said one must not forget that while it started with just one person, it eventually became a mass Movement of thousands.

“The size at the start doesn’t determine the impact. Movements grow, and so does awareness. We’re here not only for the victims of the past, but for the safety of future generations. It may not have been your loved one who disappeared in the past, but tomorrow, it could be. This is why we stand here, even if we are few.” he said.

Suffering of Sinhalese civilians

Responding to criticisms that Southern Movements often fail to acknowledge the suffering of Sinhalese civilians during the war, Skanthakumar said there should be no competition or opposition among victims. “We are here for all those who have suffered not only due to the war, but also due to enforced disappearances during the Southern youth insurrection, and for people who had no ties to either conflict but were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. The Trinco 17 case is a good example that they were completely innocent,” he said.

He said that every one of these victims deserves justice. “Of course, justice sometimes comes through criminal accountability, finding the perpetrator and punishing them. But more often, justice means changing the systems that allowed such crimes to happen in the first place,” he said.

“People in border villages, for example, were often used as political pawns placed in dangerous areas and then forgotten. Today, they suffer not because of the war, but because they’ve been abandoned. They have no water, no jobs, no livelihoods,” Skanthakumar said.

“People in border villages, for example, were often used as political pawns placed in dangerous areas and then forgotten. Today, they suffer not because of the war, but because they’ve been abandoned. They have no water, no jobs, no livelihoods,” Skanthakumar said.

“We must care for the living, not just mourn the dead. Let’s ask ourselves, can we make their lives better now? Can we help them live with dignity, just as we fight for justice for those whose lives were taken?”

“There is no excuse for atrocities like killing people in their sleep, whether it was a father, mother, or child. And yes, if those responsible can be identified, they must face justice regardless of who they are or which side they belonged to. One injustice does not cancel out another. Just because one case has not seen justice, it does not mean we should give up on all others,” he said.

Justice is not limited

According to him this is not a zero-sum game. Justice is not limited. “When we fix the politics that caused this violence, when we build systems people can trust so that no one needs to pick up arms again, then we protect everyone. Because the same system that tortured people in Mannar also tortured people in Mahiyangana. The system that disappeared someone in Batticaloa also disappeared someone in Beliatta. And they continue to get away with it for the same reasons. So, justice for one is justice for all.” he said.

The renewed attention to the Chemmani mass grave, alongside the voices raised in Colombo and beyond, underscores an enduring demand for truth and accountability in Sri Lanka’s post-war reality. Whether from the North or South, from civil societies or ordinary citizens, the message remains clear: justice must not be selective, delayed, or denied.

As the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights said in his statement to the Human Rights Council in 2022, “Truth, justice, and reparations are not optional, they are obligations. And they are essential for building a society that can move forward without leaving wounds unhealed.”

The testimonies from those who protested at the Colombo Fort Railway station reflect this broader truth. While the excavations in Chemmani continue to reveal the physical evidence of past violence, the larger challenge lies in addressing the institutional silence and impunity that have allowed such tragedies to remain unresolved for decades. In this context, public protest, no matter how small, serves not only as an act of remembrance but also as a call to prevent history from repeating itself.