In the art world in Colombo is abuzz with a compelling confluence of exhibitions, offering a vibrant commentary on Sri Lanka’s socio-political canvas.

In the art world in Colombo is abuzz with a compelling confluence of exhibitions, offering a vibrant commentary on Sri Lanka’s socio-political canvas.

At the heart of this artistic dialogue is Prof. Chandraguptha Thenuwara’s up and coming solo endeavor, ‘Neo Glitch,’ will be gracing the walls of the Saskia Fernando Gallery from July 23. Thenuwara, a luminary in confronting visual complexities, continues his iconic “Glitch” series, inviting us to peer beyond the fractured surface of our contemporary reality and discern the hidden narratives.

In a powerful parallel, his solo show is complemented by ‘HEREAFTER,’ a significant group exhibition at the JDA Perera Gallery. It will be Opening with a preview on July 23rd, ‘HEREAFTER’ gathers a formidable collective of senior artists, S.H. Sarath, Kingsley Gunathilake, Jagath Weerasinghe, Chandraguptha Thenuwara, SarathKumarasiri, Nilanthi Weerasekara, Pradeep Chandrasiri, T.P.G. Amarajeewa, Sujith Rathnayake, Pala Pothupitiya, and Chammika Jayawardena.

This exhibition promises a multi-faceted exploration of socio-political consciousness, spanning three pivotal phases of the Faculty of Visual Arts’ history, the Government College of Art, the Institute of Aesthetic Studies, and the University of the Visual and Performing Arts.

Further enriching the cultural calendar is ‘Visual Persuasions – 2nd Edition,’ showcasing the unique perspectives of nine talented women artists: Shanika Wijesinghe, Sajeewani Hewawitharana, Christine Ruth, Thilini Apsara, PiyumikaHewage, SanduniWijekoon, IreshaJayathilaka, Chathusi Premasiri, and Madhuwanthi Hapangama. Their exhibition previews on July 28 from 5 pm to 7 pm and continues until August 7, 2025.

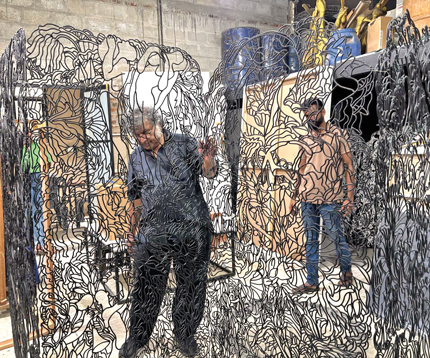

Prof. Chandraguptha Thenuwara at his workshop

Amidst this exciting wave of artistic expression, we had the privilege of sitting down with Professor Thenuwara himself. In this interview, we delve into his latest artistic approach, exploring the evocative “Glitch” effect and the profound symbolism that lies “behind the Curtain” of his thought-provoking creations.

Q: “Neo Glitch” is your latest exhibition. Can you tell us about its theme? What exactly is ‘hiding behind the glitch’ in your art?

A: “Neo Glitch” is a continuation of a concept I began in 2016, reacting to the socio-political changes after the 2015 “Yahapalanaya” government. I saw a “glitch” then – a gap between promises and reality, where new democratic freedoms were misused, hindering progress.

This “glitch” persists today, even with the new government. Despite mandates and promises, fundamental changes aren’t fully materialising. My art, using elements like skies and landscapes, reflects this unclear reality. Even with widespread national support, core issues, especially concerning land and local protests, remain unresolved. This ongoing disparity, this new manifestation of hidden problems, is what I call the “Neo Glitch.”

My work often incorporates elements like skies and landscapes to reflect this. Politicians talk about nationalistic approaches and unique solutions for the nation, and we see landslide victories with widespread public support. Yet, paradoxically, the fundamental issues, especially those related to land and local protests, remain unresolved. These demonstrations aren’t always in Colombo; they’re often happening in other areas, highlighting that disconnect.

Q: Reconciliation is a key theme in your annual exhibition, and through your art, you’re continuing to remind and remember the victims and marginalised of the political situations in the country. Can you elaborate on this connection?

A: Absolutely. My exhibitions are deeply connected to reconciliation and post-war issues. They explore the promises we made to solve problems after the war, and what we’re actually doing for all people across the entire country – whether it’s the North, West, South, or Centre – without boundaries.

But the crucial question remains: Are we truly fulfilling these promises? Often, you can’t see tangible progress. We talk about reconciliation, establishing offices, and so on, but simultaneously, opposition groups are staging protests. While protests themselves aren’t inherently bad, some of these actions create opportunities for anti-peace solutions and hinder efforts like returning land to its rightful owners. Land ownership is a significant, ongoing issue in Sri Lanka’s political and geopolitical landscape.

That’s why you’ll see a lot of landscapes in my paintings, but they’re not presented clearly. It’s a type of glitch – what you see isn’t always what’s truly there, or what’s intended. My aim is to transform these observed issues into a painting language. It’s a “glitch situation” where everything appears as a distorted, shattered image, fragmented into bits. Even when I paint a complete image, I then intentionally “glitch” it, disturbing the viewer’s proper perception. I even employ a pointillist-like approach with colour to achieve this effect, further emphasising the fractured reality.

Q: The newest addition to the series is ‘The Curtain’. Can you speak about its artistic nuances, especially your use of “three-dimensional drawing”?

A: “The Curtain” is crucial because it’s the only way I feel I can truly transfer the mood and situation of this “glitch” to the viewer. It’s not a clear picture; it functions more like a screen or a curtain. This element represents separation – it divides, creating a barrier between ‘here’ and ‘there.’

Yet, at the same time, this curtain allows you to glimpse what’s on the other side, but those images often overlap or are disturbed, preventing a clear view. It’s deliberately made to be a screen, symbolising a division. This also gives me an opportunity to continue exploring techniques from my previous work, particularly my “Covert” series, where I used iron rods.

With “The Curtain,” I’m essentially taking a drawing and transferring it into three dimensions. I’m using the iron rods to create lines and forms in space, much like lines on a paper, but they exist physically, contributing to that sense of obscured vision and fractured reality. It’s a method to convey that even when something is visible, it’s not entirely clear or accessible.

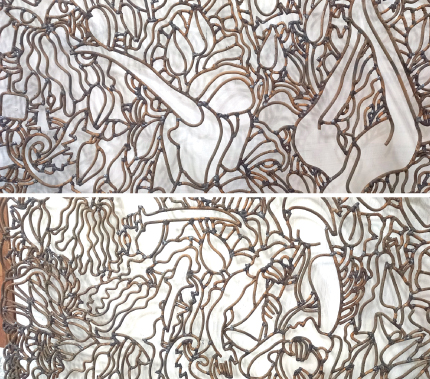

Q: Your work frequently uses “camouflage,” and in ‘The Curtain,’ we see fragmented motifs, almost like a deconstructed national flag, lotus, bells, dancers and drummers. Can you explain the meaning behind these motifs and why you chose them?

A: The concept of “camouflage” has been central to my work since 1997, even before my “Barrelism” series. It reflects how much is still camouflaged in our political discourse, and my art aims to reveal these hidden truths. “Neo Glitch” itself is another form of camouflage.

In ‘The Curtain,’ the camouflage allows you to see certain beautiful human forms and patterns initially. But hidden within this aesthetic is an ugly truth. It speaks to past nationalism and extreme religious ideologies. For example, the lotus motif holds a double meaning. While it has religious significance, it has been heavily misused by politicians for propaganda, becoming an easy symbol to connect with people’s deeply held religious beliefs.

In ‘The Curtain,’ the camouflage allows you to see certain beautiful human forms and patterns initially. But hidden within this aesthetic is an ugly truth. It speaks to past nationalism and extreme religious ideologies. For example, the lotus motif holds a double meaning. While it has religious significance, it has been heavily misused by politicians for propaganda, becoming an easy symbol to connect with people’s deeply held religious beliefs.

Beyond these, you’ll also see other elements like knives, swords, and pistols. These symbolise gang culture, nationalistic aggression, and the ongoing struggle for land. All these elements – the historical, the beautiful, and the ugly – combine into a large, leafy, floating pattern. From afar, it might seem pleasurable, like looking at the world. But as you get closer, you start to discern the bad evidence, the hidden truths. The installation itself in the gallery, by creating these visual obstacles, mimics this experience of perceiving a reality that is both present and obscured.

Q: As an artist primarily focused on political themes, how do you manage the potential stress of responding to challenging contemporary issues?

A: My art translates observations into a visual language, aiming to create beauty even from difficult truths. I maintain a consistent, old-fashioned process. I paint every stroke myself, reflecting my dedication. After each exhibition, I spend three to six months in contemplation, observing, sketching, and refining core themes. This ensures continuity and connection in my work.

My art, like “honey,” reflects society, maintaining a consistent artistic language from “Barrelism” to “Glitch.” This consistency, rooted in my technical skills and classical art influences, gives me confidence. I transform political ideas and even disasters into visual beauty, because, as an artist, it’s my duty to express the ongoing situations around me, much like the profound impact of the 1983 events that still shape my perspective.

Q: You are one of the few Sri Lankan artists with exposure to Russian classical art and you are also an academic. How do you view the Sri Lankan art academic sphere, and what advice do you have for young and emerging artists?

A: The key for any artist is continuous learning; stopping means becoming a “dead artist.” Learn your craft thoroughly, including classical fundamentals, as they underpin visual language. Critical thinking and broad knowledge beyond your field are essential. My art balances creating beauty with conveying political truth. My process involves long contemplation periods after exhibitions to absorb surroundings and refine themes, ensuring consistency. My freedom from market pressure (as a teacher) allows extensive experimentation, but I advise young artists not to let market demands compromise their artistic integrity. Develop your unique voice, and let the market follow your art.

Q: Your academy, WAFA, has been producing independent artists for almost three decades, offering an alternative to traditional university settings. How do you plan to take WAFA forward?

A: My goal for WAFA is to be an open, practising space for all aspiring artists, especially adults lacking formal university access. I plan to host artist-in-residence programs for knowledge exchange and expand WAFA into a broader creative hub – a “CAMP” (Contemporary Artists Meeting Point) for visual artists, musicians, dancers, and theatre practitioners. Emphasising continuous study and critical thinking, I teach students to ask good questions and refine their art through studio “trial and error” before public display.

My own artistic freedom, supported by my teaching income, allows me to experiment without market pressure, a freedom I encourage young artists to seek to maintain their artistic integrity amidst a growing market.