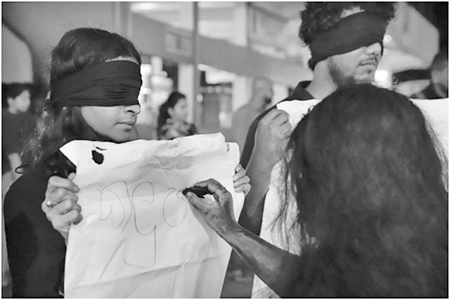

In July 2025, a quiet but resolute crowd gathered at Borella Junction in Colombo to mark the 42nd anniversary of Black July, the week in 1983 when Sri Lanka turned violently against its Tamil community. What began as a response to the killing of 13 soldiers quickly spiralled into a State-sanctioned pogrom. Thousands were murdered, tens of thousands displaced, and an entire generation of dreams, relationships, and futures were buried in smoke and rubble.

In July 2025, a quiet but resolute crowd gathered at Borella Junction in Colombo to mark the 42nd anniversary of Black July, the week in 1983 when Sri Lanka turned violently against its Tamil community. What began as a response to the killing of 13 soldiers quickly spiralled into a State-sanctioned pogrom. Thousands were murdered, tens of thousands displaced, and an entire generation of dreams, relationships, and futures were buried in smoke and rubble.

It was not simply a riot. It was the shattering of a nation’s moral compass, a deep fracture in Sri Lanka’s humanity. Black July is widely seen as the beginning of the island’s three-decade civil war. But it was also a pivotal moment of cultural erasure, when Tamil identity itself was put to the torch.

Among the burned homes and looted shops, a more subtle devastation occurred, one that turned to ash the shared stories, songs, and symbols of a pluralistic nation. Tamil-owned cinemas and film studios, once vibrant spaces of collective imagination, were reduced to rubble. This was not just the destruction of buildings, but of memory, heritage, and belonging to Sri Lanka.

Faultlines beneath the flames

To understand the tragedy of Black July, we must look beyond 1983. Sri Lanka’s post-Independence political identity was shaped by a narrowing nationalism. The 1956 Sinhala Only Act, University admission quotas, and land settlement schemes systematically sidelined the Tamil population. By the late 1970s, Tamil youth were radicalising in response to decades of discrimination, while Sinhala political elites stirred majoritarian fear for political gain.

The riots of July 1983 were not a spontaneous reaction, they were a State-enabled campaign. Mobs were armed with electoral lists, transportation was coordinated, and security forces either stood idle or joined the violence. Weeks before the attacks, President J.R. Jayewardene chillingly told the UK’s Daily Telegraph: “Really, if I starve the Tamil people out, the Sinhala people will be happy.”What followed was not just ethnic violence. It was a calculated erasure of people, institutions, and culture.

Cultural memory in flames

Rio today

Black July 1983 was not merely a week of violence, it was a State-enabled assault on an entire community’s existence. Following the killing of 13 soldiers, mobs, often aided by political operatives and overlooked by security forces, unleashed destruction across Colombo and beyond. Over 5,000 Tamil-owned businesses were destroyed. The economic toll surpassed USD 300 million. More than 150,000 people were displaced, with job losses rippling across both Tamil and Sinhalese workers.

Cultural spaces were not spared. Tamil-owned cinemas and studios were systematically targeted. In Pettah, “hardly a single Tamil or Indian establishment was left standing.” Across the city, film reels melted in the streets, posters burned, and theatres defaced with hate slogans. It was not just violence, it was cultural annihilation.

One of the first major losses was Vijaya Studios, owned by pioneering Tamil producer K. Gunaratnam. His studio, sound department, and entire archive, decades of cinema, were destroyed. As filmmaker V. Sivadasan later recalled “There were films that didn’t exist anywhere else. No VHS. No backups. When that place burned, it wasn’t just a building. It was memory, language, poetry. Gone.”

Cinemas such as Gamini in Maradana, Sapphire in Wellawatte, Kalpana in Kirulapone, Rio in Kompannavidiya, Raj in Negombo, Liberty in Badulla, Casino in Matale, and many others were set ablaze, targeted not for what they showed, but for who ran them. Many were Tamil-owned, yet they had long been beloved by audiences across ethnic and communal lines.

Among the most tragic stories was that of K. Venkat, a Tamil filmmaker celebrated for his work in Sinhala cinema. On his way to help his sister during the riots, he was ambushed in Dehiwala, shot, and burned alive in his car. His films, which honoured Sinhala folklore and Buddhist themes, stood as testaments to a shared cultural vision.“He didn’t see Sinhala or Tamil when making films,” a relative said. “He saw stories. And they killed him for his name.”His death remains a stark symbol of a unity betrayed, and of a nation’s cinematic soul set ablaze.

Rio cinema: From glittering premieres to charred memory

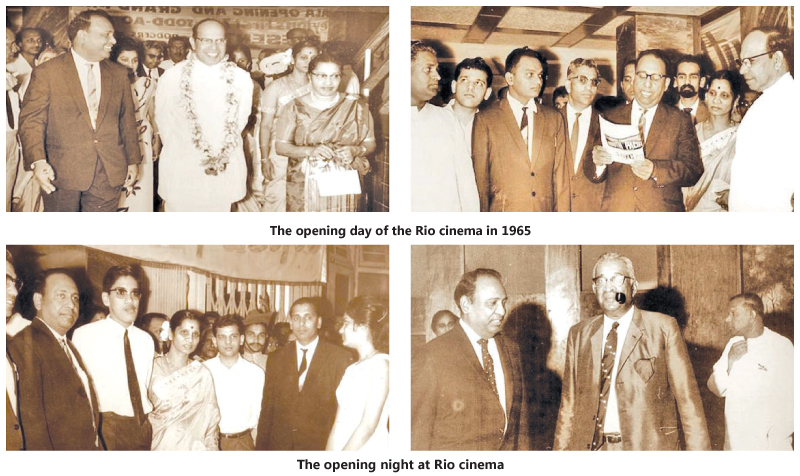

Opened in February 1965, the Rio cinema stood as a beacon of modernity and sophistication in post-Independence Sri Lanka. Boasting 600 plush foam-rubber seats, polished satinwood armrests, and the country’s first 70mm Todd-AO projection system, it brought a new era of cinematic spectacle to Colombo.

Rio screened Hollywood blockbusters such as The Sound of Music, South Pacific, Exodus, Can-Can, Lord Jim, West Side Story, and Cleopatra, offering audiences a world-class movie-going experience. Its opening night was a landmark occasion, attended by future Presidents, including then Governor-General William Gopallawa and a young Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga. Their presence is preserved in a now-faded photograph, still hanging beside Mr. Navaratnam’s old office, alongside a yellowed newspaper clipping announcing the premiere of South Pacific as the opening show of Rio.

Rio was the vision of Appapillai Navaratnam, a pioneering Tamil entrepreneur who had opened the Navah cinema in 1951, the same year his son, Ratnarajah Navaratnam known as Thamby, was born. The Navaratnam family would go on to establish a cinema empire: Trio in Dehiwala, Gem in Ragama, another Rio in Jaffna, and later the Rio Hotel, built just in time to host dignitaries for the Non-Aligned Summit in 1976 which was held in Colombo. Before the National Film Corporation centralised distribution, the Navaratnams also served as key importers and distributors of quality English films across Sri Lanka.

Nestled in the heart of Kompannavidiya, also known as Slave Island or Company Street, Rio was more than just a cinema. Located in one of Colombo’s most vibrant and multi-ethnic neighbourhoods, home to Sinhalese, Tamils, Muslims, Burghers, and Malays, it served as a shared cultural space and a bustling hub for local traders and small businesses.

In the 1970s, the Rio thrived as a cherished communal ritual: usherettes offered snacks in the aisles, families packed the halls, and people from all walks of life came together to revel in the magic of film. But as Thamby reminded us during our conversation, that dream was violently shattered in July 1983.

Smoke on Kumaran Ratnam Road

On the evening of July 25, 1983, as Black July descended into its darkest hours, a mob stormed the Rio cinema and the adjacent hotel on Kumaran Ratnam Road. They looted everything they could, furniture, equipment and valuables, before setting the building ablaze. The flames licked through the screen, melted film reels, and gutted decades of cinematic memory.

While the police and soldiers stood by, or, according to some witnesses, even aided the attackers, the proud façade of the Rio blackened in the fire. The theatre that once welcomed diverse audiences with red carpets and orchestral fanfare was reduced to a smoldering skeleton.

A long-time employee Premadasa, the cinema’s oldest staff member, hid nearby, watching helplessly as his workplace and life savings disappeared in the blaze. Ratnarajah Navaratnam, son of founder Appapillai, witnessed the destruction from across the city, unable to intervene. His father’s life’s work was crumbling, reel by reel, beam by beam. “My father was broken,” said Thambi, recalling the devastation.“Not by the money, but by the betrayal. He had served this city with pride. And this was his reward.”

The Navaratnam family fled to Australia, their loss far deeper than financial. Appapillai Navaratnam, once a towering figure in Sri Lanka’s cinematic history, never recovered from the blow. What was destroyed was not just a business, but a cultural landmark, a symbol of pluralism and pride. For years, the Rio stood abandoned, its burnt walls a haunting reminder of how easily shared spaces can be destroyed when hatred is weaponised and silence sanctioned. A jewel of Sri Lanka’s multicultural past, turned to ash by bigotry and left unaccounted for by the state meant to protect it.

Ruins remain, life stirs

A quiet gathering at Borella junction last week remembered the lives lost during the 1983 Black July terror

The Rio cinema still stands on Kumaran Ratnam Road, its once-elegant façade weathered by time, paint peeling, plaster crumbling, yet the faded 70 mm Todd-AO sign clinging on like a ghost of its golden age. Amid Colombo’s breakneck urban transformation, the Rio remains, a relic caught between ruin and remembrance.

Though gutted by fire, it has taken on a second life. Artists and photographers are drawn to its haunting grandeur. Its decaying walls have become backdrops for model shoots, indie exhibitions, and wedding photo sessions, celebrated for their raw, cinematic decay.

Yet beneath the occasional glamour lies a sobering reality. The cinema still operates, barely, as a midday purveyor of adult films, screening faded American blue movies to near-empty halls. Its vintage photochemical projector, astonishingly still in use, is the last of its kind in Sri Lanka, kept alive by two ageing projectionists who have served Rio for decades.

The one time, long-time employee still lives on-site, in a modest corridor room tucked behind the auditorium, a quiet guardian of what remains. Occasionally, art events draw small crowds back, momentarily reigniting Rio’s spirit. But for the most part, the building exists in a suspended state, neither fully alive nor completely abandoned, a time capsule, echoing the sounds of a shared past now slipping into oblivion. Today, the Rio is for sale. And with it, hangs a deeper question: Will this once-beloved space be erased in the name of redevelopment, or will it be memorialised as a site of cultural and historical significance? The answer will determine whether Rio’s story ends in silence, or continues, in remembrance.

Beyond memory

Black July was more than an eruption of violence, it was a calculated campaign of cultural erasure. Tamil homes, shops, studios, cinemas, and printing presses were not collateral damage; they were deliberate targets. These spaces, like the Rio cinema, stood as symbols of pluralism, cosmopolitanism, and the Tamil contribution to Sri Lanka’s shared civic life.

Their destruction wasn’t just about property, it was about identity. The message was chillingly clear: You do not belong here. But memory resists fire. The Rio still stands. Scarred, but upright. A few frames of films remain, tucked away in forgotten archives. And today, a new generation of artists and filmmakers, particularly from multiple communities, are beginning to respond, using cinema as resistance, and art as a testimony.

To truly honour the victims of Black July, we must demand more than remembrance. Truth and reconciliation are essential, but so too is cultural restitution. We must restore what was lost, remember what was erased, and reject the silence that injustice depends on.

As we mark the 42nd commemoration of Black July, we must understand it not merely as a tragedy of the past ,but as a mirror to the present. Black July was not a spontaneous riot. It was the culmination of decades of State-backed majoritarianism: discriminatory language laws, land grabs, demographic engineering, and systemic impunity. It escalated into a pogrom that targeted Tamil economic and cultural life. And to this day, not a single perpetrator has been brought to justice.

As Ratnarajah Navaratnam reminded us, “They didn’t even appoint a proper Commission.” Truth Commissions came and went, but justice never followed. No prosecutions. No reparations. No meaningful transformation. These injustices were engineered by politicians who manipulated narrow ethnic narratives for their own gain. And yet, there is a glimmer of hope. I take heart in the fact that many in the younger generation are beginning to think beyond those divisive frames, especially in the aftermath of the Aragalaya, which helped shift public consciousness. My hope is that Sri Lanka can carry forward that spirit of unity and collective resistance into the future.

And so, the ruins remain. But even in ruin, places like the Rio are not just crumbling structures, they are living wounds in the nation’s conscience. And also quiet acts of defiance. They carry the memory of what was and the possibility of what could still be.

Let the Rio cinema with its peeling paint and flickering reels, stand as our metaphor. Damaged, yes. But still projecting. Still breathing. Let it remind us that while politicians ignite the flames, it is the artists who carry the water, to rebuild, reimagine, and restore.

Sri Lanka’s future must be framed in pluralism.

Memory must become a force for justice, not nostalgia.

Let us say, with clarity and courage: Never again.

Say no to racism. Say yes to truth and justice

1965 opening day of the RIO photographs provided by Ratnarajah (Thamby) Navaratnam, 83 Black July photograph taken by Chandragupta Amarasinghe, the other photographs were taken by Sakuna M Gamage