In one of the most significant judicial pronouncements in the history of Sri Lanka’s legal and environmental governance, the Supreme Court delivered a momentous judgment last week in the aftermath of the ‘MV XPress Pearl’ disaster.

The ruling spans 361 pages and represents an unprecedented assertion of environmental accountability, Constitutional protections, and the “Polluter Pays” principle under Sri Lankan law.

For the first time, the nation’s highest court has ordered USD 1 billion in compensation from corporate actors responsible for marine pollution — a decision that experts say will echo across South Asia and beyond.

For the first time, the nation’s highest court has ordered USD 1 billion in compensation from corporate actors responsible for marine pollution — a decision that experts say will echo across South Asia and beyond.

A five-member Bench, led by Chief Justice Murdu Fernando PC, along with Justices Yasantha Kodagoda, A.L. Shiran Gooneratne, Achala Wengappuli, and K. Priyantha Fernando, delivered the verdict after 30 days of hearings.

The court held that the operators, owners, the captain, and the local agent of the ill-fated vessel ‘MV XPress Pearl’ jointly and severally bore responsibility for concealing critical information, violating international maritime norms, and causing the largest recorded marine plastic spill in history.

The judgment also faulted state authorities —particularly the Marine Environment Protection Authority (MEPA), its chairperson, and a former state minister — for failing in statutory duties, constituting fundamental rights violations under Article 12(1) of the Constitution.

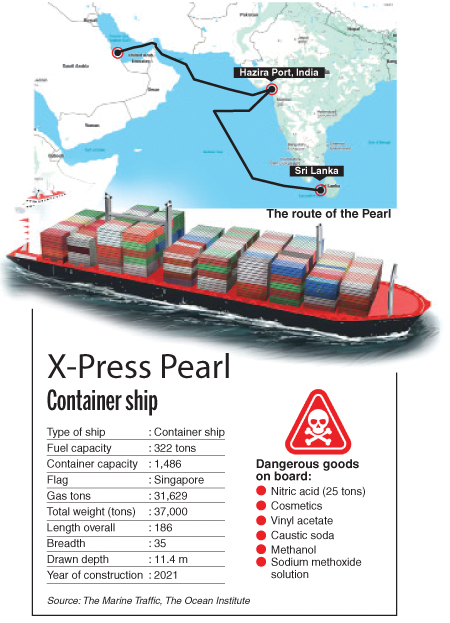

The saga began in May 2021, when the ‘MV XPress Pearl’ — a 186-metre Singapore-registered container ship carrying nearly 1,486 containers, including 25 tonnes of nitric acid and pallets of plastic nurdles —caught fire while anchored off Colombo.

Initial port calls to Qatar and India, requesting permission to offload the leaking container, were denied. The ship then proceeded to Sri Lanka, where a fire broke out on May 20, burning over nearly two weeks until it sank on June 2, 2021.

As the fire raged, toxic cargo and billions of plastic pellets —estimated between 70 to 75 billion nurdles from polyethylene containers — washed ashore along Sri Lanka’s western, southern, and northern coasts.

Beaches became littered with microscopic debris, coral reefs were smothered, marine animals perished in unprecedented numbers, and local fishing communities faced devastation. The livelihoods of thousands were imperiled as fishing bans grouped entire coastal regions for over a year.

News of this man-made disaster galvanised civil society. Fundamental rights petitions were filed by environmental and fishing rights groups — including Archbishop Malcolm Cardinal Ranjith, the Centre for Environmental Justice (CEJ), and representatives from impacted communities — seeking justice, compensation, and restoration for the damage inflicted. The petitions accused corporate and state actors of negligence and constitutional violations.

Historic legal and environmental significance

At its core, this judgment represents a watershed for Sri Lanka’s environmental jurisprudence. It marks the first time the Supreme Court has ordered a statelevel environmental reparations package of this magnitude.

Officials at the MEPA, the Attorney General’s Department, and Ministries were held personally culpable for violating citizens’ fundamental rights by neglecting statutory responsibilities and delaying legal action.

Chief Justice Murdu Fernando wrote that the deliberate suppression of information by the vessel’s operators deprived Sri Lanka of precious response time — turning what was a preventable incident into a national catastrophe. She said that State inaction also violated Article 12(1) of the Constitution, which protects equality before the law, citing the failure to convene the Marine Environment Council and coordinate pollution response.

Chief Justice Murdu Fernando wrote that the deliberate suppression of information by the vessel’s operators deprived Sri Lanka of precious response time — turning what was a preventable incident into a national catastrophe. She said that State inaction also violated Article 12(1) of the Constitution, which protects equality before the law, citing the failure to convene the Marine Environment Council and coordinate pollution response.

The court also took aim at the Attorney General for choosing civil litigation in Singapore instead of pursuing criminal prosecution under Sri Lanka’s own Admiralty jurisdiction.

This, the court ruled, was irrational and undermined justice for Sri Lankan victims. Consequently, the court ordered the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) to launch prompt criminal investigations into violations of the Marine Pollution Prevention Act and related laws — reportable to the court every three months. The Bribery Commission (CIABOC) was similarly instructed to reopen inquiries into alleged corruption.

The polluter pays principle in action

Affirming the “Polluter Pays Principle,” the court determined that the XPress Pearl Group —comprising ship owners, charterers, and local agents — must compensate Sri Lanka fully for environmental, economic, and health-related harms. The total initial compensation was set at USD 1 billion: with USD 250 million due by September 23, 2025, another USD 500 million within six months, and the remaining USD 250 million within a year. The funds are to be channelled into a newly set up “MV XPress Pearl Compensation and Environment Restoration and Protection Fund.”

The judgment also ordered the creation of two statutory committees. First, the MV XPress Pearl Compensation Commission, chaired by retired Supreme Court Justice E.A.G.R. Amarasekera, is tasked with overseeing fair distribution of compensation to affected individuals and communities. Second, the Marine and Coastal Environment Restoration Committee, chaired by the Secretary to the Ministry of Environment, will oversee restoration of beaches, coral reefs, and marine habitats. Independent environmental experts will be appointed to both bodies, required to report periodically to the Supreme Court.

The court also directed Sea Consortium Lanka (Pvt) Ltd., the local agent, to file sworn affidavits naming all directors and principal executive officers involved in MV XPress Pearl operations as of June 2, 2021 —part of a compliance and transparency mandate.

Broader impact and legal reform mandate

This ruling establishes a new precedent, signalling that both nonState and state actors can be held legally responsible for environmental harm in Sri Lanka. It reinforces the notion that environmental rights are intertwined with Constitutional assurances. It also mandates comprehensive legal reform: the Attorney General must review Sri Lanka’s maritime pollution laws and align them with international maritime protocols to prevent future disasters.

Legal scholars said that this ruling may have ripple effects beyond Sri Lanka. Similar principles have driven environmental litigation in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh — but rarely with such a sweeping payout and direct Constitutional links. By identifying senior public officials as responsible parties, the court sends a clear warning that negligence and delay in environmental governance carries personal liability.

Legal scholars said that this ruling may have ripple effects beyond Sri Lanka. Similar principles have driven environmental litigation in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh — but rarely with such a sweeping payout and direct Constitutional links. By identifying senior public officials as responsible parties, the court sends a clear warning that negligence and delay in environmental governance carries personal liability.

The environmental disaster affected biodiversity profoundly: hundreds of turtles, dozens of dolphins, whales, and countless fish washed ashore dead, while coral reefs and phytoplankton zones collapsed. The local fishing communities — many supporting multi-generational livelihoods — were banned from fishing for over a year, and had no income. Thousands of women continued to collect plastic nurdles by hand long after the spill, risking health hazards.

The judgment’s affirmation of the right to a clean environment as a Constitutional safeguard is particularly powerful. It underscores that environmental degradation is not merely a policy issue — it is a rights violation requiring remedy through the courts. This aligns Sri Lanka with global trends in environmental human rights jurisprudence.

Unanswered questions and next steps

While the judgment has raised hopes for justice, significant challenges remain. Will the USD 1 billion compensation actually be collected in full? Experts note that shipping companies often use complex corporate structures and international litigation to delay or reduce liabilities. However, because Sri Lanka-based agents are parties to the ruling and subject to local enforcement, the court noted that failure to comply could result in contempt proceedings and arrests.

Criminal investigations must now move swiftly. The CID has been ordered to conclude its investigations within three months, reporting to the court quarterly. CIABOC is tasked with identifying corruption — especially involving the timing of compensation claims and alleged suppression of evidence. The next full court review is scheduled for September 25, 2025.

The Petitioners Centre for Environmental Justice (CEJ) have welcomed the judgment, calling for full transparency in how compensation funds are managed — and for survivor communities to be directly supported. The CEJ’s legal advisor said that the ruling is a landmark for environmental justice in Sri Lanka, but cautions that implementation is critical.

Environmental experts have also commended the Centre for Environmental Justice (CEJ) for its tireless and persistent efforts in pursuing accountability and justice in the aftermath of the X-Press Pearl disaster. As one of the main petitioners in the legal battle over the environmental and economic fallout of the incident, CEJ has been at the forefront of advocacy, legal intervention, and public awareness.

Environmental experts have also commended the Centre for Environmental Justice (CEJ) for its tireless and persistent efforts in pursuing accountability and justice in the aftermath of the X-Press Pearl disaster. As one of the main petitioners in the legal battle over the environmental and economic fallout of the incident, CEJ has been at the forefront of advocacy, legal intervention, and public awareness.

Their consistent pressure on authorities to uphold environmental law, ensure transparent investigations, and pursue compensation has played a vital role in keeping the issue in the public and judicial spotlight. Experts have said that without the CEJ’s leadership and commitment, the full extent of the damage and the systemic failures surrounding the incident may never have come to light.

International context and historic comparisons

Internationally, environmental compensation awards of this scale are rare. The 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the U.S. ultimately resulted in USD 20 billion in fines and compensation; the Prestige oil spill in Spain (2002) resulted in USD 3.6 billion in liability. In Mauritius, claims following its catastrophic 2020 spill reached USD 10 billion before being dropped on legal technicalities. Compared to these, Sri Lanka’s ruling represents a significant assertion of environmental liability by a developing country.

This judgment places Sri Lanka at the forefront of environmental accountability in South Asia, illustrating how domestic courts can play a decisive role in holding global actors responsible for ecological harm.

A new era for environmental governance

Ultimately, the faultline revealed by the XPress Pearl disaster was not only physical — the ruptured ship and polluted seas — but institutional. The court’s judgment exposes how poor governance, delayed responses, and legal avoidance can worsen natural disasters. This ruling demands accountability at every level, from ship owners to Government Ministers.

For environmental law in Sri Lanka, the judgment represents both a culmination and a beginning. It cements environmental protection as a Constitutional imperative and asserts that degraded seas, poisoned livelihoods, and destroyed ecosystems must be reparable in law.

The creation of compensation and restoration institutions provides a model for future disasters and sets standards for transparency. The court’s willingness to name and penalise state actors — as well as private ones — marks a new era for governance and integrity.

Whether the fullest measure of justice is delivered now depends on implementation: payment of compensation, restoration of the environment, prosecution of violators, and legislative reform. Yet even as these processes unfold, Sri Lanka’s Supreme Court has already sent a clear, historic message: environmental neglect has consequences, and the courts will enforce accountability.

For Sri Lanka’s marine environment, coastal communities, and future generations, last week’s ruling may be the clearest sign yet that environmental justice is no longer aspirational — but achievable.