This week, we have reached out to a giant in the Sri Lankan performing arts scene; Dr. Indika Ferdinando. He is a renowned Sri Lankan theatre and film director, playwright, filmmaker, dramaturge, and academic.

This week, we have reached out to a giant in the Sri Lankan performing arts scene; Dr. Indika Ferdinando. He is a renowned Sri Lankan theatre and film director, playwright, filmmaker, dramaturge, and academic.

He earned his first-class honours degree in Drama and Theatre from the University of Kelaniya and has since taught at the University of Kelaniya and the University of the Visual and Performing Arts in Colombo. He pursued his Ph.D. at Monash University in Australia, investigating how multisensorial elements of Sinhalese ritual performances can be adapted into contemporary theatre practice.

Indika has written and directed multiple acclaimed theatre productions and feature films. His debut feature, Ho Gaana Pokuna (The Singing Pond, 2015), received international recognition and awards at notable festivals including Chicago, Zlín, and Shanghai His follow-up film, Vedi Nowadina Lamai (Bulletproof Children, 2020), was an official entry at China’s Golden Rooster Awards and was described as a dark comedic thriller blending musical elements with social commentary.

Indika has also earned accolades for his theatrical work, becoming the youngest recipient of the Best Director award at Sri Lanka’s National Drama Festival. His body of work spans experimental theatre often merging ritualistic, sensory-rich traditions with modern storytelling and feature films that explore social and emotional themes through compelling, narrative-driven styles.

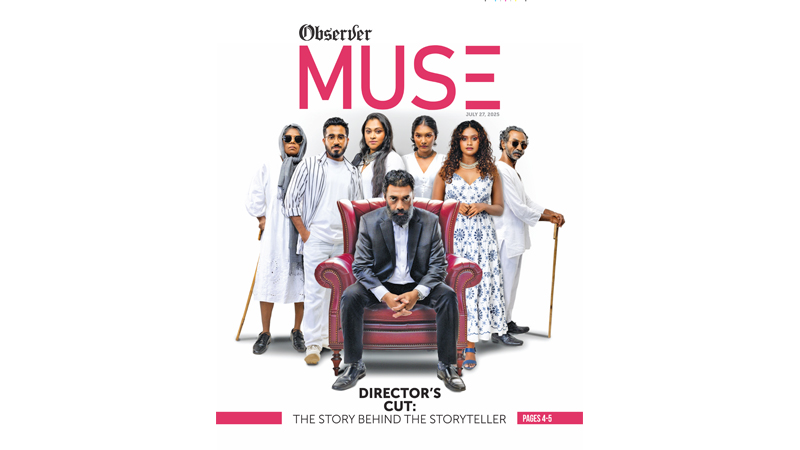

Dr. Indika Ferdinando

Indika has cooked up a new state production ‘Secret Files, which premieres on August 2 and 3 at the Lionel Wendt. This is said to be a musical melodrama that is guaranteed to use genre-blending and socially reflective storytelling.

We dove into a very heartfelt interview with Dr. Ferdinando to get glimpse of his body of art, his process and his inspirations and here’s what we found out;

Q: You’ve navigated between theatre, cinema, and academia with remarkable ease. How do these different disciplines influence each other in your creative process?

A: That’s a very interesting question. Now, anyway, each area that you mentioned is about exploring the human experience. They each offer a unique lens through which to explore that experience, right? When it comes to theatre, it gives you the possibility of sharing a very intimate experience with the audience.

It’s a very intimate connection with your audience and a very raw, live one. I mean, theatre is about sharing the same breath with your audience. And when it comes to cinema, it gives you the possibility of magnifying life in a way that theatre cannot.

It’s like having a binocular and a microscope at the same time. On the other hand, academia allows you to reflect, scrutinize, critique, and analyse, so they are very complementary. In a way, even in research, you are doing a kind of storytelling. In each area or in each discipline, you have to have a narrative. So for me, it’s a very effective way of expressing myself.

Q: Having said that if you had to pick one discipline for life which one would it be?

A: That’s a very hard question to answer again. Now I have married all three of them and I can’t live without any one of them, so I will not pick one because I cannot.

Q: In your theatrical works, there’s a strong presence of Sri Lankan ritual and sensory elements. Could you talk about how ritual performance traditions influence your stagecraft?

A: The thing is, I did my PhD at Monash University, Australia, and the subject area I explored in my research was the possibilities of reinventing the multisensorial experience of Sinhalese rituals in contemporary theatre practice. My first encounter with a Sinhalese ritual was when I was a university student. By that time, I was already a very enthusiastic theatre-goer, but the experience produced by the ritual I witnessed or rather, experienced was something entirely different. Actually, “witnessing” is an inappropriate word to describe the ritual; it’s something you experience.

In traditional, middle-class theatre, the investment is primarily in the eyes and ears, it’s an audiovisual experience. You hear things, you see things. But in a ritual, you hear things, you see things, you smell the fragrances, and you are touched by the ritual in various ways. You are even offered food. It’s a multisensorial experience and a holistic way of engaging the senses of not the audience because even terms like “spectator” or “audience” are inappropriate in the context of ritual but rather the participant or attendee.

This fascination led me to try taking elements from ritual and bringing them into contemporary practice. The ritual experience isn’t merely an aesthetic one, it’s a transformative experience. Rituals are meant to transform people. Even a birthday party is a ritual. A puberty ceremony, maybe Kothahallu, for instance, a wedding, a funeral, these are all transformative experiences. That is the uniqueness of ritual. There are also performative rituals such as Daha Ata Sanniya and others, which deeply interest me. But really, even day-to-day events are rituals. My point is: rituals are transformative, and I believe that art practice should be transformative too. So I believe incorporating them in my statecraft makes it a transformative experience too.

Q: Your debut feature film Ho Gaana Pokuna resonated deeply with audiences, especially for its treatment of childhood and imagination. What inspired that story, and how did you shape it for the screen?

A: The first thing is that my main focus as an artist is about the experience that is generated by the art that I’m making, whether it’s a theatre experience or a cinematic experience. Even my doctoral study was about experience. I want to present a very compelling experience for the audience, something that is irresistible, compelling, effective, immersive. So, the material that I use for my films and theatre, the material I choose is always considered in terms of how effective it will be in generating that kind of experience.

When it comes to Hoganapopuna, it’s based on personal experience; two personal experiences, actually. One was when I was travelling in the northern part of the country. I visited a government-run cultural centre. This was before 2009, during the war, and the whole area was affected. Even the building of the cultural centre showed evidence of war damage to the walls, the roof, it was visible. But at the heart of that centre was a brand-new piano. I was shocked and also thrilled by the sight. I was told it had been donated under a World Bank project. I felt that the piano was the last thing they needed. But at the same time, I thought, if someone had known how to play that piano, things might have been different. The lives of the people might have been different.

When it comes to Hoganapopuna, it’s based on personal experience; two personal experiences, actually. One was when I was travelling in the northern part of the country. I visited a government-run cultural centre. This was before 2009, during the war, and the whole area was affected. Even the building of the cultural centre showed evidence of war damage to the walls, the roof, it was visible. But at the heart of that centre was a brand-new piano. I was shocked and also thrilled by the sight. I was told it had been donated under a World Bank project. I felt that the piano was the last thing they needed. But at the same time, I thought, if someone had known how to play that piano, things might have been different. The lives of the people might have been different.

And then once, I was involved in an almsgiving at a child care home in Wattala, very close to the beach. After the children had lunch and dessert, I asked them what they wanted, if there was anything they wished for, because it was heartbreaking to see children in such a situation. They told me, “Please take us to the beach to see the ocean.” The tragic part was that the ocean was just 500 metres away. But they couldn’t go there was no one to take them. That was it.

The shapes of tragic experiences are different. That’s what I asked myself. Why? Why are they so underprivileged? Those two experiences inspired me to tell a story about a group of underprivileged kids, away from Colombo’s fascinations, who have a desire to see the ocean.

But it’s not about the ocean, it’s not about seeing the ocean. The theme of the film is something deeper. The ocean is a metaphor. We all have desires like that, at different levels. We’re all underprivileged in some way. We have to be our own heroes, because superheroes are limited to movies and comics. And it is also our duty as humans to be heroes for the underprivileged, if possible.

Q: Having worked extensively in both mediums, how would you compare the storytelling freedoms and limitations of film versus theatre in a Sri Lankan context?

A: Theatre in Sri Lanka is more and enjoys more freedom than film. Yes, I mean, obviously, it is because the audiences are smaller, so, theatre is a kind of it’s not an institutionalised art; it is run by people or groups of people, artists who have this affection for theatre. So the state bothers less about theatre practitioners. But when it comes to film, we know that it is a public art, and it has the capacity to attract a significant number of spectators.

Therefore, by scrutinising the history, we can see that the state is more worried about film, not theatre, because it has a broader reach. And also, the nature of the two art modes because theatre is live and momentary. The existence of theatre is temporary. It exists only when it is being performed. But cinema, it is permanent. When it is shot and edited and when you finish the film, until the end of the world, it will be there.

So, therefore, I mean, cinema confronts censorship more than theatre. I think anywhere in the world, that is nature.

Q: As a working artist, what are some other works of art, including theatre and cinema or creators of cinema or theatre that you are inspired by?

A: Oh, there are so many I am deeply inspired by. The storytelling of Spielberg fascinates me, his ability to craft effective and irresistible cinematic narratives is truly remarkable. I’m also very drawn to the negative complexity of David Leitch, and the decorative simplicity of Majid Majidi, the creator of Children of Heaven.

Some of my favourite creators include Bertolt Brecht, Dario Fo, Ivo Van Hove, and Rob Marshall.

I really admire Brecht’s philosophical stance, his approach to human relationships and character, and how he draws from legend and folklore. He travelled the world to tell stories; for example, he went to China for The Good Woman of Szechwan. He explores different human emotions and how people react to situations in the most magnificent manner.

When it comes to Dario Fo, I’m particularly inspired by his comedic style and his ability to find humour in contemporary political and social behaviours, his work in political satire is brilliant.

And Rob Marshall; I just love how he choreographs, creates, and musicalises human social situations. For instance, Cell Block Tango from Chicago tells a powerful story of four women in just one song. I want to be able to do that.

Q: When you are creating something either stage production or cinematic, please, what is your process?

A: My process is that every piece of art I have created is a result of research. This is how the three disciplines I’m married to just complement each other, like I said earlier.

So my debut play Janadipathi Thaththa was an experiment in tragicomedy. Usually, a tragicomedy would be tragic from the beginning and would have a happy ending. However, this experiment was comedic from the beginning and had a tragic ending and experience overall.

And my play Colombo Colombo was about suggesting/explaining the articulation of linear plot construction. Also, it was an experience in minimalistic theatre, basically using less and less external material and maximising the skills of the actors.

And my most recent play, Secret Files, is a musical melodrama, or something that sensationalises situations and relationships, creating circumstances without regard to the reality or rationalisation of that situation, characters in poetry in motion, of people in a mood, romantic manner.

Q: This brings us to our last question, about secret files, let’s talk about your most recent production? What can we expect?

A: Secret Files, like I said, is a musical melodrama. The reason for using this technique is because in recent years, theatre had less drama than actual life. So, theatre did not capture the social trauma of life, and I’m trying to bring that melodrama into the theatre play.

Speaking about what to expect; well, you can expect a lot of drama and music, very talented actors, and a good time.

The plot of the drama is about a very famous businessman who was shot dead, and he’s given a second chance to mend his ways and leave us as a good person. I would like this play’s purpose to be about being good or just in an unjust world.

The play will also be performed in September and October after the premiere.