The roundabout adjacent to the Old Town Hall, bordering Sea Street, Colombo 11 is a very busy place. It is a confluence of vendors, customers and somewhat agitated motorists. With the exception of Sundays, this is a happening extension of the bazaar that extends from Main Street. On one side it is bordered by opulent stores dealing in jewellery, and in contrast the right side of the road is home to dealers of virgin coconut oil who trade in barrels.

Amidst this activity, there are two men, sharing a wooden stool. They are positioned in the middle of an elevated platform, resting on the pavement that separates the road.

Amidst this activity, there are two men, sharing a wooden stool. They are positioned in the middle of an elevated platform, resting on the pavement that separates the road.

They obtain part of their shade from a sturdy tree, which is also shared by a few curious crows that caw incessantly. The rest of their shade comes from a large multi coloured plastic umbrella which has withstood the heat of Colombo and lost much of its hue. These men are the last of a rare breed of skilled workers, who sustain their lives by sharpening knives and other blades.

Primitive contraptions

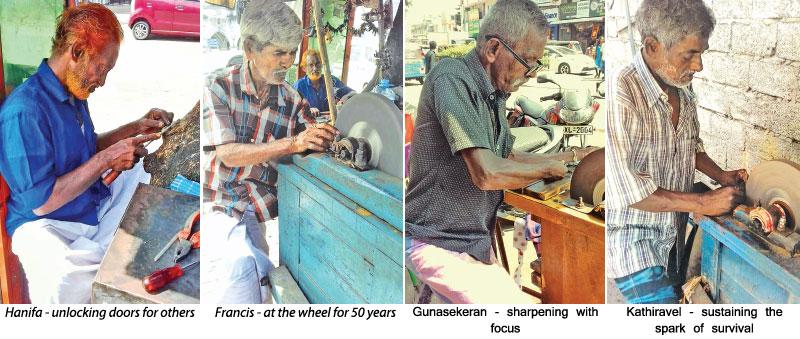

The older of the two men eyes me with curiosity. After a casual greeting Francis shares his story, “Ah, I thought you wanted to sharpen a knife. So you’re going to write about me?” When I nodded, he smiled and said, “I came to this pavement when I was a boy of 14 years, to work with my father. Can you believe I have been here for the past 50 years, same place same trade. I am from the Grandpass area.

This has been my life and livelihood,” he points at his sharpening machine, painted blue. These somewhat primitive contraptions are centered on a wooden box, with a protruding single cycle wheel (minus the rubber casing), which extends a rubber cord, which in turn gives life to the large flint wheel. The force to work the wheel is generated by a foot operated pedal. The blades are sharpened on the spinning flint wheel, the speed regulated according to blade size.

Francis, 64, is a bachelor. He said, “I have seen the city of Colombo changing. Those days, people used to sharpen a lot of knives. Servants brought foreign knives from big mansions around the city. The Ceylon era was our golden period. Now they use stainless steel knives’.

The man seated beside Francis looks like a character from Aladdin, his hair and robust beard tinted brown, glimmers in shades of copper in the intense heat of the sun. Hanifa, clad in a white sarong has his own memories of working on these vibrant streets. “I am also here for the past 45 years. I am married. This is part of our lives. Working side by side with Francis, my profession is to cut and carve keys. At times I also sharpen knives and repair knife handles. There are days we make 1,500 rupees, and some days 500 rupees, but during rainy days we earn nothing.” As I observed their tools Hanifa and Francis share a king coconut to quench their thirst. It was a beautiful bond of cultural co-existence in the heart of the city, a Christian and a Muslim working in peace. The men begin their day at 8 am and wind up around 6pm. They often share their lunch and tea.

A few feet away, across the pavement is another old man in a grey shirt. A silver cross hangs on a chain around his neck. His black framed spectacles might afford him the look of a learned librarian, but Gunasekeran is another relic of yesteryear. He is sharpening a pair of scissors. My tap on his brazen shoulder seemed to alarm him. His hands display varicose veins, and continuing to strain at the flint wheel he said, “Today we charge Rs 100 to sharpen a knife, and Rs 150 to sharpen a pair of scissors. Yet, the ladies who come try to bargain, and sometimes we yield to their bargaining. We have spent our lives on these streets,” he says in a voice that betrays regret.

The noonday sun continues to shine, as carters navigate their way transporting sacks of tamarind and onions. Some pigeons hover over the swaying sacks.

Left behind

Walking along Sea Street, I turned to Kathiresan Street where I was told the last of these knife sharpeners could be found. Kathiresan Street is a virtual reflection of Jaffna, with many Northern vendors. Songs of Hindu devotion are blaring out from a tea boutique. On the right hand corner is a solitary umbrella, under which a man, in an unkempt white beard, is at work. He is Kathiravel, and is happy that someone had come to hear his story, for they all feel forgotten and left behind. Kathiravel has been here along with his father, for decades. He recounts, “My father came to this area in 1960. There were no vehicles or traffic then. The people brought their cooking knives to be sharpened. Women used to sew at home- so the girls would bring their pair of scissors for sharpening. My father is no more and I’m here for almost 40 years, now. I have two sons and a daughter. My elder son is a tailor. Our lives are a daily challenge. In the good old days we enjoyed succulent fish and meat and watched Tamil movies, but today that is a luxury. Also, now people use digital devices to cut and chop, and soon we may have no business. I depend on sharpening scissors from textile shops in this area.The cost of a new sharpening contraption is almost 30,000 rupees, and the heavy flint stone costs 8,000 rupees, which we have to replace”.

These four men have seen the victories and vicissitudes of Colombo. They have served a generation, and share calloused hands and finger nails stained with flint. As the sun sets, they sip tea and share a few moments in companionship.

I had seen one more of these old men along Slave Island, Colombo 2, but could not locate him. Perhaps, he has faded into the sunset. For these hardworking men, there are no pensions or retirement benefits. The flint wheel continues to spin, but their peaceful destiny remains out of reach.