Two young professionals at a coffee shop talk about how they are using ChatGPT to lighten their workload while a sponsored post on an AI app pops up in your Instagram feed while you sip your latte on a Monday morning. And then you have the ‘four-day work week’ with Belgium and Portugal following suit after a several UK companies widely adopted it in January this year.

Although a four-day work week may sound ludicrous in Sri Lanka, our two-year bout with Covid-19 which forced us to ‘work from home’ and recent experimentation with generative Artificial Intelligence software like ChatGPT and Stable Diffusion by the Millennial and Gen-Z workforce begs the question: How will our future jobs look when we can get work done with a single tap of a button?

There are many ways this current can go. A best case scenario is the great efficiency that will make overall tasks so much more easier – giving us more free time to pursue hobbies and spend time with our loved ones. Or it can make jobs even more mundane by piling task after task because things have gotten easier. Jobs have been made useless with each technological revolution, but we have been resourceful and creative in terms of creating jobs and things for people to do.

Amorphous blob

According to anthropologist James Suzman, most of us work in this great ‘amorphous blob’ called the services sector. “Within that services sector space, there’s an awful lot of work which is work we’ve simply created because we feel that humans cannot live without organised work, and also because we organise our societies on that basis. Certainly now in these societies based on fossil fuels and ever more productive machines, there actually isn’t a lot of very good work for everybody to do, yet we insist on full employment, and it is a product of the fact that we are doing work just for work’s sake”.

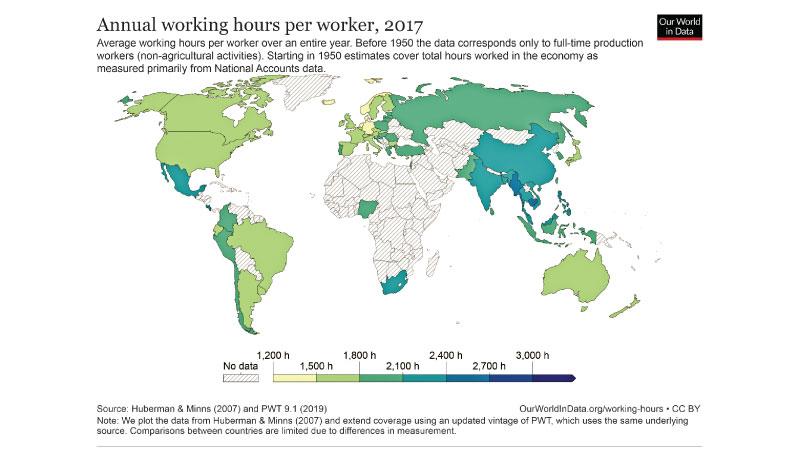

In an essay published in 1930, ‘Economic possibilities for our grandchildren’, economist John Maynard Keynes predicted that people will be working only 15 hours per week. While this prediction is coming true to countries that experienced early-industrialisation, according to one 2020 data-based survey published in Our World in Data, which found that working hours for the average worker have decreased dramatically over the last 150 years, there are differences between countries.

In an essay published in 1930, ‘Economic possibilities for our grandchildren’, economist John Maynard Keynes predicted that people will be working only 15 hours per week. While this prediction is coming true to countries that experienced early-industrialisation, according to one 2020 data-based survey published in Our World in Data, which found that working hours for the average worker have decreased dramatically over the last 150 years, there are differences between countries.

For some countries, such as Germany, working hours have continued their steep historical decline; while for other countries, such as the US, the decline has levelled off in recent decades. In South Korea, for example, hours rose dramatically between 1950 and 1980 before falling again since the mid 1980s. And in other countries, we see no recent declines — in China, for example, hours actually rose in the 1990s and early 2000s before levelling off in recent years.

But do these trends mean that developing nations in general and service sector jobs in specific are looking at a cushy, all-expense paid future with less work hours and more free time while developing nations pick up the slack? There are many implications to be explored with respect to the global outsourcing market that has been growing since the 1980s.

American anthropologist and anarchist David Graeber theorises the concept of useless occupations, which are jobs that individuals believe are pointless, unnecessary, or even harmful. These jobs often involve pretence and lack of genuine value. Graeber categorises these jobs into five types: flunkies (tasks done to make others feel important), goons (aggressive roles that exist due to others’ employment in similar roles), duct-tapers (jobs created to fix problems that shouldn’t exist), box-tickers (jobs aimed at creating an appearance of action without actual impact), and taskmasters (those who assign and supervise unnecessary tasks).

Graeber gives two examples; one museum guard tasked with watching over an empty room and an office worker who had to copy paste emails.

“I worked as a museum guard for a global security company in a museum where one exhibition room was left unused. My job was to guard that empty room, ensuring no museum guests touched anything, though there was nothing in the room and ensure nobody set any fires. To keep my mind sharp and attention undivided, I was forbidden any form of mental stimulation, such as books and phones. As nobody was ever there, I sat still and twiddled my thumbs for seven and a half hours, waiting for the fire alarm to sound. If it did, I was to calmly stand up and walk out. That was it,” the security guard said.

The office worker described their role involving monitoring an inbox for tech help requests, copying the emails from a certain format, and pasting them into a different format.

This task was initially automated, but became manual due to managerial disagreements and subsequent standardisation.

Anti-work

The Great Resignation, also called the Big Quit and the Great Reshuffle, is an ongoing economic phenomenon that started in early 2021 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. It involves a significant number of employees resigning from their jobs, driven by reasons such as stagnant wages, higher cost of living, limited career growth, negative work environments, lack of benefits, inflexible remote work policies, and enduring job dissatisfaction. The trend is most noticeable in industries such as hospitality, healthcare and education.

Sri Lanka’s massive brain drain is an aspect of this trend that is being played out in developing countries, where a frustrated youth from the Global South are increasingly pursuing greener pastures or are seeking education abroad in hopes that they can land a job after graduating. This coupled with the Covid experience of working from home and the advent of AI tools has introduced a culture of ease.

The widespread adoption of remote or hybrid work has led persons to appreciate the value of spending time with their families, reevaluate the lengthy commutes they used to make, and question the necessity of being physically present at a distant office desk. However, it’s important to note that the concepts of anti-work sentiment and “The Great Resignation” are somewhat rooted in privilege such as being from the first-world, ones income and profession. As global unemployment rates decrease, the availability of well-paying jobs might decrease as well, potentially making frequent job changes more challenging. Additionally, not everyone will have the financial cushion or the option to rely on their parents’ home while navigating periods of unemployment.

The arrival of the ‘digital nomad’ and AI chat bots in the scene opens the door for the ‘anti-work’ era to begin, albeit this can only apply to those with certain conditions. However, the term “anti-work” can be misleading. The philosophy behind it doesn’t oppose the idea of working or putting in effort, but rather criticises the exploitation of the labour force. It challenges the notion that we should exhaust ourselves, risking burnout and health issues, to sustain an ever-expanding and voracious system.

Monotonous work

It’s not necessarily against capitalism itself, but rather questions the types of jobs (and bosses) that dehumanise individuals into mere resources. The essence of the anti-work concept envisions a world where survival doesn’t depend on selling our labour. We’ve all come to accept the narrative that we’re obligated to trade hours of monotonous work for the essentials such as rent, food and utilities. In essence, anti-work could be better interpreted as advocating for fulfilling work.

In this rapidly evolving landscape of work, where technology and societal shifts are shaping our job paradigms, a complex interplay of forces is redefining our relationship with labour. The convergence of trends such as the rise of AI-driven tools, the experimentation with shorter work weeks, and the growing sentiment of anti-work reflect a multifaceted transformation in how we approach employment.

The concept of anti-work challenges us to question the relentless pursuit of productivity and economic growth at the cost of our well-being. It’s not about shunning effort, but rather advocating for meaningful, purpose-driven work that respects human dignity. As we witness the Great Resignation, and the ‘Great Brain-Drain’ here in Sri Lanka it’s clear that many are seeking roles that align with their values, offer work-life balance and provide a sense of fulfilment beyond just financial gain.

However, the journey toward a more balanced and fulfilling work environment is not a universal path. It’s a privilege often associated with developed nations and specific circumstances. The shift to remote work, the advent of AI-driven tools and the rise of the digital nomad lifestyle offer opportunities for some while highlighting inequalities for others who lack access to such privileges.

As we contemplate a future where technology and changing attitudes towards work intertwine, the key lies in finding a harmonious balance. This balance involves reimagining the nature of work, challenging the notion that our worth is solely defined by our labour, and addressing the disparities that prevent equal access to opportunities. It necessitates a shift towards valuing the quality of our experiences, nurturing our well-being, and embracing the idea that a successful life encompasses more than the grind of a traditional job.

The ongoing transformations in the world of work are reshaping the narratives we’ve inherited. While the “anti-work” sentiment highlights the importance of meaningful and fulfilling endeavours, it also reminds us to be mindful of the privilege associated with pursuing such aspirations. The path ahead involves reconciling technological advancements, economic realities and our collective desire for a more balanced and enriching work-life existence. As we navigate this complex journey, the pursuit of meaningful work and a re-imagined understanding of productivity can guide us towards a future where work truly serves the betterment of humanity.