“I can speak the language and based on my previous experiences, I believe I can handle the work once I re-migrate, and I don’t need further training,” says Ms Herath Manike of Maho, Kurunegala.

She had previously migrated to Kuwait and Jordan as a domestic housekeeping assistant and is now contemplating re-migration.

Returnee migrant workers often possess a wealth of knowledge and skills acquired during their time overseas, leading them to feel adequately equipped for the global job market. However, in today’s rapidly evolving international job market, adaptability and acquiring new skill sets are essential for sustained career growth. Relying solely on existing skills can lead to complacency and hinder long-term prospects.

Continuous up-skilling can open doors to more stable and higher-earning employment opportunities. The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM) also underscores the necessity to invest in skills development and promote mutual recognition of skills, qualifications, and competencies.

A recent study by the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS) for Skilled and Resilient Migrant Workers (SRMW) project focusing on 511 returnee migrants in Sri Lanka revealed that among the surveyed participants, 56% of respondents had taken steps towards re-migration, and 193 are considering re-migration in 2023.

Among them (of 193), 68% have not pursued further formal training. Moreover, 84% of these respondents believed their current skills were sufficient for overseas employment. As Sri Lanka unveils its Labour Migration Policy 2023-2027, it is timely to shed light on the importance of skill development for re-migration.

Potential for upskilling

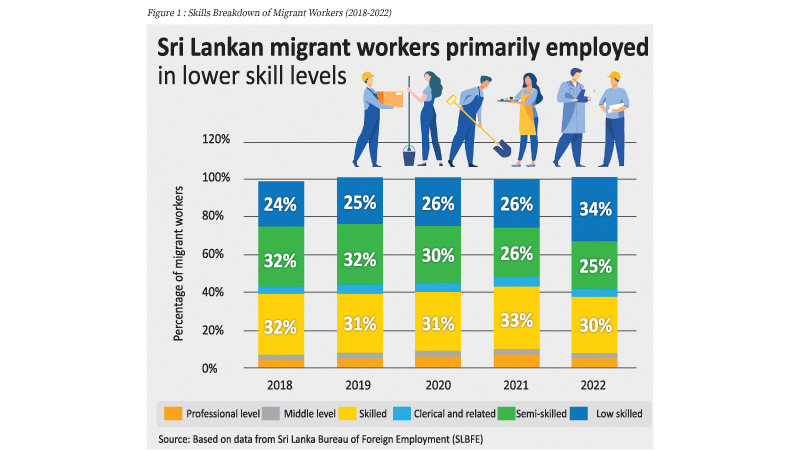

In Sri Lanka, migration is looked upon as a promising pathway to improved job opportunities, as evident from the recent long queues at passport offices. A significant proportion of Sri Lankan migrant workers were in semi-skilled and low-skilled categories (see Figure 1). Most labour migrants are concentrated in Middle Eastern countries, which are common destinations for both skilled and unskilled workers. This aligns with the study findings, which indicated that many of these migrants were engaged in elementary occupations (domestic workers and other low and semi-skilled categories) during their recent overseas employment.

Although most re-migrants from Sri Lanka have been employed in lower-skilled jobs, they have great potential to improve their prospects by acquiring new skills through upskilling.

However, the practice of upskilling is not widespread among this group. For example, Sri Lanka predominantly relies on foreign domestic workers among its migrant workers. However, there is a growing demand for specialised services like nursing and elderly care. These specialised jobs often offer better pay than foreign domestic workers.

Enhancing the skills of returning domestic workers can open up job opportunities in sectors beyond domestic work, particularly in healthcare.

Reluctance

Ms Manike, who pursued a small coir business after her recent migration, is now facing economic difficulties that have led her to consider re-migration. However, she hesitates to participate in skill development programs, driven by her immediate need to generate income through migration and her confidence in her past experience. Therefore, her primary focus is on addressing urgent financial needs, leaving limited space for dedicating time and effort to upskilling.

Similar to Manike’s perspective, most returnee migrant workers planning to re-migrate believe their previous training or experience from overseas would suffice, overlooking the need for continuous skill upgrading.

In scenarios where re-migration is not voluntary but a necessity due to compelling circumstances, individuals may be forced to re-migrate without the opportunity or motivation to upgrade skills to pursue better employment opportunities overseas.

If returnee migrant workers consider upskilling, many often opt for informal training or overlook skill development due to perceived opportunity costs and age-related barriers associated with formal skill training programs available in the country.

They fear that dedicating time and resources to formal training might not yield immediate returns on investment, leading them to choose informal learning options instead. Age-related concerns can make some migrant workers reluctant to enrol in formal training, as they feel they are past the ideal age for learning new skills.

Another significant barrier to skill sdevelopment for returning migrants is the lack of targeted and tailored training programs. For instance, during a Focus Group Discussion (FGD) conducted in Anuradhapura, reluctance to undergo formal training on the grounds that there is no suitable training available in Sri Lanka for the specific machines used while working abroad, was cited as an example.

As these workers aspire to find better opportunities upon their return, access to advanced and customised training becomes a pivotal factor in their career growth.

Skills gap and awareness

While Sri Lanka has taken many steps to provide support services for upskilling and skill recognition for migrant workers, such as the recent collaboration between the SLBFE and the Vocational Training Authority (VTA) to offer specialised training tailored to foreign employment needs, concerns remain regarding the effective dissemination of vital information to the intended beneficiaries.

As found in the IPS’ study, while a majority of respondents have completed their education up to Grade 10, surprisingly, only 20% were aware of National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) levels. Although returnee migrant workers tend to favour informal training, a notable 76% (out of 511 individuals) had not acquired Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) credentials.

These credentials serve to formally acknowledge the skills acquired through informal means. This highlights a significant gap and lack of awareness regarding formal skill development and recognition among the respondents.

The way forward

While the self-perceived competence of returnee migrant workers is a positive attribute, relying solely on existing skills without further training and formal recognition of available qualifications may hinder the personal and professional growth opportunities of returnee migrant workers.

Therefore, it is crucial to foster a culture of lifelong learning and skill development to support returnee migrant workers in their re-migration journey and enable them to thrive in a dynamic job market.

This involves creating awareness about the importance of ongoing education and training and providing accessible and relevant learning opportunities. Some recommended strategies include:

Improve dissemination of information and guidance about skill development programs and raise awareness about the importance of upskilling.

Facilitate awareness and accessibility to available skills development programs through easily accessible user-friendly platforms like websites or mobile applications.

Foster collaboration between the public and private sectors and educational institutes to develop targeted training programs specifically tailored for migrant workers planning to re-migrate. These programs should align closely with industry needs and incorporate hands-on experience.

Establish networking and mentorship programs that connect migrant workers with professionals in their fields, providing guidance, collaboration opportunities, and skills enhancement support. Promote existing RPL and accreditation of informal skills, encouraging migrant workers to pursue upskilling opportunities. – Institute of Policy Studies (IPS)

The writer is a Research Assistant working on migration and urbanisation policy research at IPS.