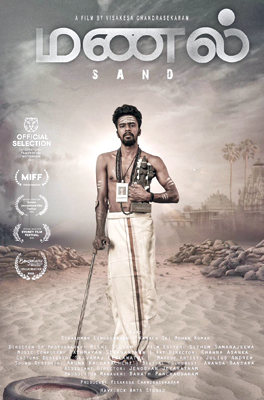

Munnel, the critically acclaimed film by Visakesa Chandrasekaram, is set to captivate audiences as it embarks on a limited release from November 3 in selected theatres. This highly-anticipated cinematic creation has already made waves in the international film festival circuit, garnering widespread recognition and even earning Visakesa Chandrasekaram a Special Jury Award at the prestigious International Rotterdam Film Festival.

In a recent interview with the Sunday Observer, Visakesa Chandrasekaram talked about his creative process, sharing insights into his distinctive approach to filmmaking, casting, and storytelling. As an artiste with a remarkable background as a human rights lawyer, his commitment to portraying the experiences of victims and marginalised communities shines through in his work. With his exceptional ability to balance ambition with practicality, Chandrasekaram’s Munnel promises to be a thought-provoking and emotionally resonant cinematic experience.

Q: While the core stories of Paanshu and Munnel may seem similar, the approach to filmmaking is strikingly different. In Paanshu, you assembled a professional cast and crew, from actors to cinematographer, resulting in a polished production. However, with Munnel, you took quite the opposite route. This bold decision lent an authentic feel to both films, considering the geopolitical aesthetics of their content, and showcased your sophistication in filmmaking. Could you please share more about this creative process and what led you to make this choice?

A: I appreciate your observation, and you’re right, my approach to filmmaking for Paanshu and Munnel was indeed quite distinct. To clarify, I should mention that I don’t consider myself a mature filmmaker, as making films is more of a sporadic pursuit for me due to my primary daytime job.

Munnel’s beginning dates back a long time, with several drafts and revisions. The process was organic, and when I initially conceived it, there was a lack of talent in Jaffna for certain production roles. However, over time, people from the region had the opportunity to go abroad for film-related training. For example, Rishi Selvam attended the Korean Film Institute and took the cinematography course. When I was ready to bring Munnel to life, there were individuals in Jaffna who were interested and had developed their skills in the field.

I also consider myself somewhat of an outsider, both in the Sinhalese and Tamil communities. This outsider status arises from my extended period of living abroad and, to some extent, my sexual orientation. These factors sometimes kept me on the fringes of certain social circles. Yet, as an outsider, I believed it was crucial to engage with the community and encourage them to take ownership of the story.

I also consider myself somewhat of an outsider, both in the Sinhalese and Tamil communities. This outsider status arises from my extended period of living abroad and, to some extent, my sexual orientation. These factors sometimes kept me on the fringes of certain social circles. Yet, as an outsider, I believed it was crucial to engage with the community and encourage them to take ownership of the story.

To make this happen, I invited three key individuals to become associate producers. I explained that I didn’t have the budget to pay them upfront, but if the project turned a profit, I would compensate them. In the meantime, they had to assist with line production tasks. This collaborative effort included Rishi handling cinematography and production management and serving as an assistant director and another critical contributor to all three of my films was Situm, who played a vital role in keeping the post-production process organised and refined.

His influence greatly contributed to the polished final product. I consistently highlighted their roles because they were instrumental to the project’s success. This collaborative, grassroots approach allowed us to make the most of our limited resources.

For me, the filmmaking process is as important as the final product. While the technical quality of the film is significant, I’m willing to compromise it if it means maintaining the authenticity, ownership, and ethics of a community’s story. In Munnel I prioritise the storytelling process and the community’s genuine involvement. This focus on process, combined with our unique approach, resulted in a noticeable difference in technical quality between Paanshu and Munnel. However, I believe it was the right choice for Munnel, as it allowed us to capture the essence of the story and its geopolitical context effectively.

Q: If you continue further with the unique cast and crew of Munnel, it is evident that you worked with a relatively young cast and crew, except for the mother’s character played by an experienced Tamil actress. How has this choice enhanced the quality and freshness of the final production?

A: As I embarked on the journey of making Munnel, I found myself in a distinctive position. When I created Frangipani, I played a “big brother” role to many of the individuals involved; they were younger than me. Now, at 53, the cast and crew of Munnel were young enough to be my own children. I felt a nurturing responsibility, and looking back, it might have been a reflection of not having children of my own.

This sense of responsibility led me to want to protect and mentor them, to assist in their growth. The most significant part of this process was sharing whatever knowledge and experience I had with them. However, it’s important to note that they weren’t inexperienced; they were already quite knowledgeable. After all, you can’t successfully complete a project like this without considerable skill and expertise. I consider myself extremely fortunate to have had the opportunity to work with such talented and capable individuals.

Working with a mix of actors and non-actors in “Munnel” was indeed a unique experience. I wouldn’t exactly call them non-actors, as some had previous experience. For instance, the mother’s character had a background in acting, particularly from the black and white film era. She was quite camera-savvy due to her prior work, albeit in smaller roles.

Sivakumar Lingeswaran who played the main character, had also dabbled in short films and worked behind the camera as an assistant director. Despite being in his early 30s, he had substantial experience. “Munnel” was his first feature film, but I wouldn’t classify him as a non-actor either.

Munnel

Then there were those who truly had no experience in front of a camera. Vani’s character had some theatre acting background, being a performance art student at the university, but film acting was new to her. Another person who had never faced a camera played the character with a mental illness, a beggar.

So, the challenge was how to blend these two groups seamlessly. It was indeed a daunting task. But I was fortunate to prepare them extensively through rehearsals and get them to use a common set of acting tools.

I encouraged all the actors, regardless of their background, to adopt the same tools. Even if they had diverse acting skills, I guided them to use a specific set of tools unique to my work. It became a way of life for them during the production period.

This approach unified their performances. It focused on how they could translate their thoughts, motivations, and character history into words, movements, and expressions. Each actor was occupied with the character’s internal world, leaving no room for thoughts like, “Do I look good from this angle?”

To ensure they remained in character, I employed techniques such as internal monologues and gave them materials to be preoccupied with their roles. While there were instances where this approach didn’t work perfectly and required adjustments in the editing process, most of the time, the actors delivered performances while genuinely inhabiting the character’s state of mind. This approach, I believe, contributed to the authenticity of the performances in “Munnel.”

Q: For a discerning viewer of your cinematic career, it is evident that you focus on stories about victims and marginalised communities. This aligns with your background as a human rights lawyer and makes perfect sense. In progressive societies, it is the norm to shed light on the experiences of victims. Thanks to these progressive interventions, cinema, literature, and policies have been developed that show empathy and address the issues faced by marginalised individuals. Currently, being a victim can wield significant influence, and coming from a marginalised background can be a source of power. As an artist, how do you perceive and navigate this dynamic?

A: Indeed, my work in both law and cinema is strongly influenced by my experiences with victims and marginalised communities. In the field of law, the scope is often limited, dealing with one case at a time and rarely engaging in public interest litigation. Nonetheless, since my return to Sri Lanka five years ago, I’ve been involved in cases like the East Attack case. The frustration stems from the constraints of this domain.

During the height of the war, I interacted with torture victims, a memory that remains vivid and influential. This experience left a lasting impact, which is reflected in the themes of torture in both my films. My own sexual orientation plays a role in this, although I don’t consider myself a victim in this context, given my privilege. However, the frustration of not being able to fully express my feelings is palpable. This is a struggle that many may not fully understand.

The frustration is compounded by the fact that much of the discourse surrounding these issues is Western-centric, and we need to develop indigenous narratives. This frustration found an outlet in my artistic endeavors, including cinema. Throughout my career in various mediums, I’ve found that my legal background informs my approach, fostering a distinct analytical perspective.

Munnel

My training as a lawyer has wired my brain to analyse situations from a legal standpoint. This analytical lens is something that carries forward in all my work. Sometimes it may be too upfront or unconventional, as seen in my book “King and the Assassin,” where I included a constitution. This unusual approach stems from my background as a lawyer and artiste.

When it comes to my films, not every character is shaped by my legal perspective, but it occasionally influences the narrative. For instance, Vani in “Munnel” shares her past experience, and I appreciate the depth this character brings to the story. My experience as a lawyer allowed me to imagine how certain situations, like being taken to the CID, might feel and appear to the characters. This insight is informed by my work with people who have gone through similar experiences.

In my films, portraying the aftermath of trauma is essential. While some may question the depiction of characters as stunned and unable to speak, it’s a reflection of the common response to trauma. People often experience this kind of trauma and have difficulty expressing themselves or reliving traumatic events. The portrayal of trauma aligns with the reality of many survivors.

Moreover, in my films, there’s often a balance between portraying victims and individuals who maintain a sense of power or self-preservation. For example, the mother in “Munnel” projects strength, and even if it’s partly a facade, she believes in her own power. Similarly, the mother in Paanshu may seem like an innocent woman, but she conceals a hidden weapon, demonstrating her agency.

Ultimately, my goal as an artist is to offer hope to victims and marginalised communities. As a human rights activist, this is paramount. It’s essential to convey that there is still the potential for change, justice, and a brighter future. While this approach may lead to unconventional narrative shifts, it aligns with my commitment to human rights and social justice.

Q: Munnel received significant recognition in the international film festival circuit, and the theme is quite familiar to audiences, especially coming from Sri Lanka. How would you characterise this recognition?

A: Yes, the theme is familiar and, for the audience, it’s easy to recognise what’s being conveyed. To be honest, I didn’t anticipate it would receive this level of recognition. The theme of a mother and son, a rebel returning home in a broken state, searching for love, is indeed a common one. We’ve seen variations of it many times. However, it hadn’t been told in Tamil for the Tamil and Sinhalese audiences, and that was my intent.

Looking back, I contemplated why this film received such acclaim when, initially, I didn’t see it as fundamentally different from my previous work, like Paanshu. After some reflection and revisiting the visual references and materials, I realised that there was a profound historical context behind these elements, something I had taken for granted but that the audience had not.

It appears that this historical context and the cultural significance of the film’s themes resonated strongly with the international audience. In contrast, Paanshu didn’t receive the same level of recognition; it was submitted to various festivals, but it wasn’t taken as seriously.

Q: Don’t you think the ritualistic approach you took in the film Munnel set it apart from Paanshu and made it more appealing to the international festival circuit?

A: You know, it’s a very new idea, and it wasn’t something I initially considered. I had no knowledge of the specific events happening in Jaffna, where religious activities gained prominence after the war. Jaffna has always been a very ritualistic society, but during the war, these aspects were somewhat suppressed, not by the LTTE, but by external factors.

After the war, these rituals made a significant comeback. I believe these elements were subtly present in the film, and I took them for granted. However, it seems that foreign audiences appreciated the cultural and historical context. They recognised the political underpinnings within the narrative.

As a storyteller, I primarily crafted the story through my imagination. While I had some awareness of these underpinnings, I chose not to explicitly convey them. Foreign audiences seemed to pick up on these elements and made references to them. I believe this added to the film’s success, as Munnel delves into these aspects more deeply than Paanshu.

Paanshu, on the other hand, is a film where you become emotionally involved with one character, sympathising with them throughout their journey. Munnel, in contrast, has an element of alienation, which may have appealed to western audiences who prefer a more detached viewing experience. Munnel helps viewers to observe from an outsider’s perspective, maintaining a certain objectivity. It might not evoke the same emotional involvement as Paanshu. This detachment was not something I purposely aimed for; it happened organically.

Q: Given the absence of a well-established film industry or filmmaking infrastructure in Sri Lanka, based on your experience, what do you believe would be the most effective model for producing films in the country?

A: Well, after working on three films, I’ve come to realise that the filmmaking process in Sri Lanka is quite unique and often calls for a different approach. It’s a bit of a balancing act.

First, you have to think big when it comes to the story. It’s not about the size of the cast and crew; it’s about the story’s impact. You want to tell a story that hasn’t been told before, something significant and different.

But here’s the twist – when it comes to execution, you have to act small. My first film, Frangipani was made on a shoestring budget, and honestly, many in the industry couldn’t believe how we managed it. I won’t reveal exact figures; there’s a lot of goodwill involved that you can’t put a price on.

I experimented with a different model for Paanshu, trying to anticipate income to cover costs. Unfortunately, it didn’t pan out as expected, partly due to the timing – the Covid-19 pandemic hit. However, our latest film, Munnel, was another interesting challenge. In this niche, you can’t expect big earnings, but we were fortunate to win a cash prize and earn some money through international sales, along with a few thousand dollars from festivals and private screenings.

From a production perspective, the key is to act small. You don’t need all the bells and whistles, and the director doesn’t need a fancy chair. Sometimes, you may have to put your dream project on hold and focus on something more manageable that fits the local industry’s capabilities.

Part of this process involves being open to script editing. You might have to cut a visually stunning scene for the sake of the story’s integrity. It’s a compromise. Some might argue that the shot is the story in cinema, and while that’s true, you can’t have it all.

Collaboration is vital. I often work with less experienced but passionate individuals who are willing to contribute for lesser costs or even for free. It’s a give-and-take relationship. For example, in my latest film, none of the three key team members charged for their work, and we all valued the experience.

Effective planning is essential. Rehearsals and preparation help reduce the need for retakes during filming, saving time and resources. While some may advocate for multiple takes to get the perfect shot, I believe in nailing it in the first or second take whenever possible.

Efficiency is another focus. Everyone should be treated with respect, and we must maintain a healthy, harassment-free environment. This not only ensures a smooth production but also respects the dignity of everyone involved.

In a nutshell, my approach to filmmaking in Sri Lanka involves thinking big in terms of storytelling but acting small when it comes to execution. It’s about finding the right balance between ambition and practicality and making the most of the available resources.