Although the Colombo Film Society would become Asia’s oldest such group, Colombo lay a world or two away from the rest of Sri Lanka. The urban middle-classes encountered the best of regional and Western cinema before their counterparts in Bombay and Calcutta did, but they remained detached from the majority who never as much as came across English films.

The rural middle-classes, on the other hand, had a somewhat different conception of the cinema. The idea of a film theatre was alien to them: they were familiar with travelling cinemas and drama troupes instead. It was later, when they migrated to Colombo, that they came across the world beyond the Madras studio and the Nurti drama.

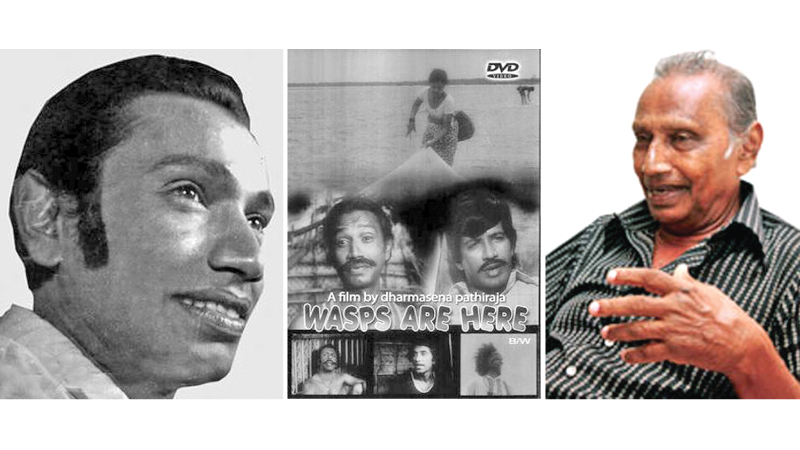

Cyril Wickramage hailed from this milieu. Born in Kohilagedara in Kurunegala on January 26, 1932, Wickramage grew up on a diet of Sokari, Nadagam, and Nurti. Kohilagedara lay less than 75 kilometres from Negombo, and drama troupes from there would visit his village. The villagers grew to love these shows so much that they soon became the centrepiece of Avurudu festivities: “When April came, we would look forward to yet another Nurti drama.” These encounters thus became an integral part of their experience.

His life as a teacher

Like Abeywickrema, Wickramage did not get to see many films in his early years. The closest movie theatre, the Imperial, was in Kurunegala town, and that lay 12 kilometres away from Kohilagedara. Yet he would not infrequently get together with his friends, and sometimes his family, and go there. “Back then we didn’t see many English films. Most of them were in Sinhala or Tamil.”

Wickramage was about 15 when the Minerva Players released Kadawunu Poronduwa. He did not readily admit it to me, but perhaps the symbiotic link between the early Sinhala films and Nurti and Nadagam drama appealed to him. In any case, it wasn’t just Sinhala films that he liked: he remembered doting on Jayalalitha also.

Wickramage’s first love was the Army. Having flirted with the idea of joining the military, however, he let it go in favour of a career in teaching. Having left school, he enrolled at the Peradeniya Training College for a two-year course. Thereafter, he was employed as a teacher at seven schools: they included the Ratmalana Deaf and Blind School and Wesley College in Colombo.

These stints not only helped him get deep into a career he had grown to love, they also enabled him to pursue his love for music, drama and dancing. More than any other institution, it was Wesley that got him thinking about the performing arts. Wesley was seeing its peak years in the 1960s. Wickramage could not escape it.

Participating in a school play, Wickramage made the acquaintance of Ananda Samarakoon. Samarakoon encouraged the young teacher to try his hand at the theatre. While the muse beckoned, however, it was the cinema that would officially initiate him to the world of the performing arts. In 1965, Wickramage got his first role, opposite Vijitha Mallika, in Kingsley Rajapakse’s Handapane. Though a minor role, it got him much praise from those who knew him. The connections he had set up during these years turned to his advantage when, a few months later, he was contacted by Siri Gunasinghe. Gunasinghe would doubtless have seen the man’s talent for playing introspective characters and he cast him in the role of the tragic protagonist in his first and only film, Sath Samudura, in 1966.

Gunasinghe’s film was a watershed in many ways. As the title implies, Sath Samudura was set in a fishing community. It was not the first Sinhala film to be set in such a milieu: just the previous year Gamini Fonseka and Joe Abeywickrema had enthralled audiences with their performances in Getawarayo, which wound up as the Best Film at that year’s Sarasavi Awards. Yet Sath Samudura was the first Sinhala film to explore realistically, with no artifice or contrivance, the torments and agonies of the country’s fishing community. While far from being a docudrama, the story rang true in ways that other films based in such settings did not. Wickramage’s performance, as with the other performances – Denawaka Hamine’s and Swarna Mallawarachchi’s – helped make the film more authentic.

These were, by all accounts, exhilarating years for the Sinhala cinema. The revolution that Lester Peries unleashed through Rekava (1956) was still being felt everywhere, and by everyone. Following him in his wake were an entirely different generation of cineastes, who owed their careers to him, but sought to go beyond his vision. Siri Gunasinghe’s film was a landmark in the Sinhala cinema, yet it did not fundamentally question or challenge Lester’s conception of the medium: it too belonged to the humanist-realist mode.

Next stage

At this point, Wickramage befriended three people who would figure in the next stage in the Sri Lankan cinema: Linus Dissanayake, producer of Sath Samudura; Vasantha Obeyesekere, Gunasinghe’s Assistant Director; and Dharmasena Pathiraja.

Dissanayake helped finance and produce Obeyesekere’s debut film, Wes Gaththo, in 1970. Cast as the protagonist, Wickramage revelled in the role of an uprooted, wayward urban dweller.

Five years later he gave one of his best performances in Obeyesekere’s Walmath Wuwo. Cast opposite the likes of Tony Ranasinghe, the film explores the plight of university graduates, who seek fairer climes and migrate to the city with much expectation, but instead find a life of perpetual drudgery. It depicts the hopes, dreams, wishes, torments, and agonies of a promising, but thwarted Sinhala petty bourgeoisie.

Between Wes Gaththo and Walmath Wuwo Wickramage took part in a great many films. Among those he befriended in this regard were Dharmasena Pathiraja and Daya Tennakoon. Through his films, Pathiraja had brought together a group of actors that, while not formally a repertoire, nevertheless became a regular feature of his films. These included Tennakoon as well as Amarasiri Kalansuriya and Vijaya Kumaratunga. The films made now were full of rebellion, and the directors who made their mark here wanted to break free from the limits of the past. No director symbolised that more fittingly than Pathiraja.

Wickramage’s best performance in a Pathiraja film would have to be in Bambaru Avith (1977). The film is an allegory about the intrusion of robber baron capitalism into the lives of a fishing community. Wickramage is affianced to Helen, a beautiful fisherman’s daughter played by Malini Fonseka. The protagonist of the story, Victor (Vijaya Kumaratunga) soon becomes infatuated with her. The film does not explain why exactly Wickramage’s character hates Victor passionately, but the conflict between Victor and the community exacerbates because of Helen’s relationship with these two men.

When television came to Sri Lanka in the late 1970s, Wickramage found a different niche. He played diverse characters from different milieux. Sometimes, they are sympathetic. In Ella Langa Walawwa, for instance, it is Wickramage who holds the narrative together as the servant, and in Kadulla, he epitomises the conflict between the old order and new in 19th century colonial society. Both these were directed by Pathiraja. They would be followed by other serials, the most memorable of which would have to be Ananda Abeynayake’s Kande Gedara. Here, in contrast to his earlier roles, he plays a conman.

Recent performances

Over the next few years and decades, Wickramage would mellow gracefully. Though he does not act as much as he used to, his recent performances unearth a more empathetic, world-weary, sagacious side to him. His career resembles that of other supporting actors, such as Daya Tennakoon, who never became leading men, but who became indispensable parts of the films they starred in. Today, at 91, Wickramage has become an elder statesman of the Sinhala film. Whether or not the honours due to him have been paid is debatable. That he is deserving of these honours, of course, there is no doubt.

– The writer is an international relations analyst, independent researcher, and freelance columnist who can be reached at [email protected]