In an exclusive interview with the Sunday Observer, we explore the illustrious career and significant contributions of Dr. Shahidul Alam, a distinguished Bangladeshi photojournalist, teacher, and social activist.

Our conversation unfolded following my meeting with Dr. Shahidul Alam at the recently concluded Prince Claus Symposium 2023 in Colombo. His compelling speech, centered around the theme ‘Truth to Power,’ stood out as a highlight of the symposium, drawing considerable attention from participants. Intrigued by his insights, I had the opportunity to sit down with him amidst the hustle and bustle of the event, digging deeper into the nuances of his remarkable career.

Our conversation unfolded following my meeting with Dr. Shahidul Alam at the recently concluded Prince Claus Symposium 2023 in Colombo. His compelling speech, centered around the theme ‘Truth to Power,’ stood out as a highlight of the symposium, drawing considerable attention from participants. Intrigued by his insights, I had the opportunity to sit down with him amidst the hustle and bustle of the event, digging deeper into the nuances of his remarkable career.

In his speech, Dr. Alam addressed the importance of speaking truth to power and the role of artists and activists in challenging injustice. He reflects on his experiences in Bangladesh and highlights the power dynamics that exist within societies, where those in authority control the narrative. Alam discusses his efforts to challenge the garment industry and shares his perspective on the global political landscape, particularly focusing on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

He emphasises the need for creative and non-confrontational ways to engage people in activism, such as through art and merchandise that carry meaningful messages. Alam calls for collective action and suggests concrete ideas, including organising exhibits of cancelled shows and questioning institutions aligned with oppressive policies. The speech encourages individuals to exercise their rights, stand against tyranny, and emphasises the impact of citizens coming together to demand change.

He emphasises the need for creative and non-confrontational ways to engage people in activism, such as through art and merchandise that carry meaningful messages. Alam calls for collective action and suggests concrete ideas, including organising exhibits of cancelled shows and questioning institutions aligned with oppressive policies. The speech encourages individuals to exercise their rights, stand against tyranny, and emphasises the impact of citizens coming together to demand change.

Q: In your speech, you emphasised the significance of speaking the truth to those in positions of power. What do you see as the role of individuals in creating a just society?

A: I’ll begin by highlighting the dynamics of power and its intended correlation with responsibility and accountability. Ideally, those in power should be held accountable for their actions. However, in reality, the power structure often shields the powerful from being held accountable. This creates a situation where the more powerful someone becomes, the more insulated they are from facing consequences.

Breaking this pattern is crucial, and the reason it persists is because individuals tend to perceive themselves as powerless, yielding space to the powerful to act without accountability. In doing so, we inadvertently relinquish our own agency. It’s important to recognise that as individuals, we possess strength, and collectively, we have even greater strength. Unfortunately, we haven’t fully exercised this collective power.

Dictators and autocrats can act with impunity because they face little opposition. Many individuals remain silent in the face of repression and abuse of power, allowing these spaces to be occupied by those who seek to consolidate power. Therefore, at every juncture, each one of us should become a friction point, impeding the unchecked ascent of power and advocating for accountability.

Q: Photography is your medium of expression, and your work is more related to activism. How do you define the role of art in activism? In your process of activism, do you position art in a secondary place, or how does it work?

A: Firstly, I don’t define myself as an artist; I see myself more as a storyteller. The reason for this is that the powerful often legitimise their position by controlling the narrative.

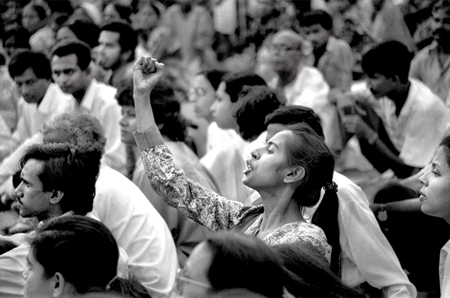

Shahidul Alam photography

Despite using force and strength, they establish themselves as rightful figures by shaping the narrative, justifying their position and rewriting history to suit their narrative. To counter this, I engage in storytelling. I utilise art, photography, and words—whatever is effective at a given time. The objective is to disrupt and shift the narrative, preventing the powerful from self-legitimisation.

As a human rights activist, I find art to be a potent tool because it can penetrate on an emotional level in ways that other means cannot. It can evoke strong emotions, linger in one’s thoughts, and influence perceptions deeply. Art, to me, is meaningful in the context of its ability to bring about social change. I’m not interested in art for its own sake; while I respect those who create aesthetically pleasing or intriguing works for various reasons, my focus is on using art as a vehicle for the social change I aim to instigate.

Q: Nowadays, social media plays a pivotal role in activism and shaping narratives, democratising the power of storytelling and challenging the gatekeepers of traditional media. However, there’s an equal challenge of spreading false information and narratives. How do you understand this paradox?

Shahidul Alam photography

A: Certainly, there is a significant challenge in navigating this paradox. My organisation, DRIK, pioneered the digital revolution in Bangladesh by introducing email in the early 90s, envisioning the use of technology for public good. As you rightly pointed out, technology can be employed in either direction. While social media offers a platform for activism, it also presents ample opportunities for the spread of misinformation. Notably, the government itself emerges as a major source of misinformation, deploying a considerable workforce to deliberately disseminate false narratives. A government-backed think tank, functioning as a propaganda wing, produces influential content that is then amplified through social media.

The challenge intensifies with the presence of troll agents. When individuals express criticism against government narratives, bots and troll agents attempt to suppress dissent. Tactics like false copyright claims are employed, making it difficult for individuals to counter these actions promptly. By the time one can address these issues, considerable damage may have already occurred. Compounding the problem is the state of mainstream media, which no longer fulfills its traditional role as the fourth estate. Self-censorship and substantial corporate ownership have compromised the media’s ability to act independently. Consequently, social media becomes a crucial avenue for the general public to express dissent and share alternative perspectives.

Q: Pathshala is your visionary educational institute where you have implemented alternative education practices. Can you elaborate on the philosophy behind it?

Shahidul Alam photography

A: The term “Pathshala” originates from the old Sanskrit word for school. The concept is akin to an open-air school without walls, drawing inspiration from the traditional image of wise individuals sharing knowledge under a tree. Our pedagogical methodology mirrors this approach. In our classes, individuals with varying skill levels participate together, fostering a collaborative learning environment. Emphasising questioning over strict technique or methodology, the focus is on instilling critical thinking and understanding the “why” behind actions.

This unique learning mechanism has proven remarkably successful. Pathshala currently stands as the only photography school in South Asia offering a degree program. We provide a four-year degree accredited by Dhaka University, the largest public university in the country. Additionally, we offer an 18-month postgraduate diploma in film and television. Our diverse student body includes individuals from North America, Europe, India, and beyond, choosing Bangladesh as the destination for learning in one of the world’s finest photography schools.

Q: In your speech, you mentioned that you set up a women photographer collective to address gender and class issues.

A: While the impact may not have been as extensive as I had hoped, it has made a difference. The exhibition we organised at the Shilpakala Academy, the Academy of Fine and Performing Arts, where women photographers showcased their work for the first time, had a notable influence on many women now active in art and media. The exhibition travelled to the UK, received publication coverage, and generated celebratory discussions. However, the outcomes didn’t fully align with my expectations. One reason, I believe, is that all the women in the collective were from the middle class, and their values and perspectives were predominantly middle class. Consequently, the critical questions and challenges we had hoped to emerge did not materialise.

Recognising this, I began teaching photography to working-class children, some of whom are now my colleagues and established professionals. Although attempts were made to replicate this in a village, the city-centric nature of the initiative posed challenges, leading to a less successful outcome compared to the city-based program. Looking forward, I see the next generation as the torchbearers for such initiatives. I believe everyone has a role to play, and at Pathshala, the educational institute I founded, the transition is evident. Initially, I was the only local teacher with a predominantly international faculty. Now, out of 26 teachers, 24 are former students, including the Photographers Protik, Asad and Taslima whose work I showcased.

It is now their role to carry forward the vision, and I anticipate they will take it in diverse directions, which is perfectly acceptable. The evolution of the idea doesn’t necessarily need to adhere to my original concept.

Q: Why have you chosen to do what you have been doing?

A: I am a product of 1971. In a broad sense, my generation experienced the genocide, and our aspirations for a free nation were rooted in the idea of an egalitarian society. The majority of those who fought for our liberation were ordinary people, many of whom were farmers in the fields—unlike someone like me.

While there were individuals like me, the essence of the liberation struggle was embodied by the ordinary Bangladeshis. I vividly recall a photograph of a woman in a sari carrying a gun while dragging two children across a field, symbolising the sacrifices made for our liberated nation. We owe it to those people. The true essence of liberation, in my perspective, lies in the liberation of the average, ordinary person.