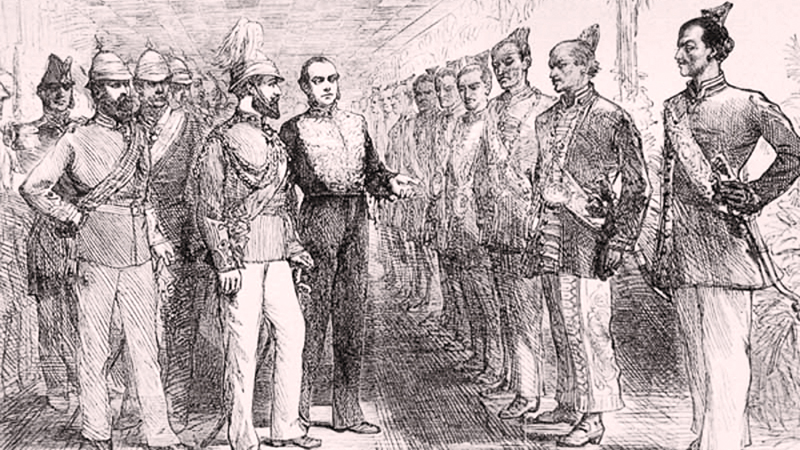

Sri Lanka’s independence unfolded in stages. In 1948, the country formally gained independence from British rule. This marked the first stage of independence. Eight years later, in 1956, the Bandaranaike government initiated a significant shift by establishing Sinhalese as the primary language of administration, replacing English.

This move towards linguistic independence solidified Sri Lanka’s autonomy. In 1972, the country transitioned to a republic, abolishing the position of a governor-general previously representing the British Crown. This step completed the formalisation of Sri Lanka’s independence as a separate and sovereign nation.

Sri Lanka’s independence brought about several changes, including a cultural shift. The country’s central literary heritage lies in Sinhala and Tamil, yet the English branch experienced significant growth after independence.

According to Lakshmi de Silva’s research, Sri Lankan English literature developed a distinct identity following independence, although earlier works, like the first English-language novel published in 1917, laid the groundwork. While these pre-independence writings may not be highly acclaimed by critics, they offer valuable context for understanding the themes and development of post-independence literature.

Profiling Sri Lankan English literature

Prof. DCRA Goonetilleke presents a comprehensive field analysis in his book Sri Lankan Writing in English. He starts by placing Sri Lankan literature within the larger international context, recognising how the literary canon has expanded to encompass new themes like postcolonialism, cultural studies, and feminism. This global perspective helps position Sri Lankan literature in a broader framework and allows readers to appreciate its unique contributions. The core of the study explores the evolution of Sri Lankan English literature, focusing on the post-independence period. Social and political forces, such as the 1956 linguistic revolution, significantly shaped this evolution.

A key challenge for writers was reconciling their cultural sensibilities and traditions with their inherited Western literary heritage. Professor Goonetilleke highlights the diverse responses writers adopted towards English, with some, like Lakdasa Wikkramasinha, advocating for its complete abandonment, while others, like Yasmine Gooneratne, embraced its potential for expression. That debate on the use of the English language in literature has subsided now, signifying a shift in focus.

Goonetilleke delves deeper by examining the impact of specific historical events, such as the 1971 Insurgency and the ongoing ethnic conflict. He cites Bryan de Kretser’s If You Have Tears as an example of how the 1971 uprising forced writers to confront the loss of innocence. Similarly, Jean Arasanayagam’s A Country at War uses poetry to express the anxieties and uncertainties of the ethnic crisis. Both events, Goonetilleke argues, pushed writers beyond their class limitations, leading to more diverse and authentic creative expressions.

The study then delves into specific genres, including drama, poetry, fiction, and short stories. Dedicated chapters explore themes like migration, identity, and the legacy of colonialism. He acknowledges the achievements of Sri Lankan English literature despite its relatively small talent pool. Goonetilleke highlights its active participation in internationalising English as a creative medium.

Postcolonial nuances

The prefix ‘post’ often indicates something new following an earlier movement. Applying it to Sri Lanka’s literary scene requires nuance. Independence in 1948 marked a political shift; hence, the enduring influence of colonialism demands a more profound lens. The academics turn to postcolonial literature rather than post-independence writing to grasp Sri Lanka’s literary landscape.

Why choose ‘postcolonial’ instead of ‘post-Independence’? Sri Lanka’s colonial rule wasn’t simply a historical chapter. It influenced language, identity, and social structures. This influence grew even after independence. Postcolonial literature digs into these effects, exploring themes of cultural hybridity, resistance, and the search for a unique voice.

Gaining independence was significant to Sri Lanka as a nation. However, it wasn’t the sole trigger for literary change. Postcolonial literature acknowledges the complex interplay of historical, cultural, and social factors that continue to shape Sri Lankan narratives. Sri Lankan writing joins a rich international dialogue exploring the legacies of colonialism across diverse geographical and cultural contexts.

Another critical concept within postcolonial theory is otherness, which refers to the experience of being marginalised or excluded from dominant cultural norms. However, this concept poses its own challenges. Otherness inherently encompasses both a sense of belonging and difference. Individuals categorised as other by a colonising power simultaneously resist its defining authority while inevitably absorbing some of its values and meanings.

The past for colonised people is only partially recoverable. Reclaiming it entirely is impossible. Instead, engaging with the past requires a delicate approach, acknowledging its fragmentation and revisiting it in partial and multifaceted ways. The notion of going home again is irrelevant in this context.

Ceylon’s independence catalysed exploring these nuances in literature. Writers often struggled with questions of national identity, cultural heritage, and the lingering effects of colonialism. Their works challenged simplistic understandings of otherness and instead embraced the complexities and diversities within the postcolonial experience.

Bridging worlds

The exploration of postcolonial themes in Sri Lankan literature extends beyond the borders of Sri Lanka. This is where diasporic literature comes to the surface and blends with postcolonial literature as an alternative consequence of colonialism’s historical impact. Suppose postcolonial writers struggled with the legacies within their homelands. In that case, diasporic writers can be identified as a species that explored the displacement and cultural negotiations experienced by communities scattered across the globe. Michael Ondaatje is a case in point. His writings take us across the complexities of belonging and identity shaped by colonial history within Sri Lanka and their subsequent diasporic experiences.

This phenomenon is well captured in an introductory essay titled The Life of Forgetting in Twentieth- and Twenty-First-Century British Literature by Adèle Cassigneul and Sylvie Maurel. They quote Salman Rushdie’s essay Imaginary Homelands that describes the Indian-British novelist’s visit to Bombay after two decades and the jarring realisation that his family’s old home appears different in person than in the old photograph hanging in his study. Facing the house with its vibrant colours, he acknowledges a painful truth:

“The colours of my history had seeped out of my mind’s eye” (Rushdie 9).

This shift from the grayscale of memory to the vividness of reality evokes a sense of loss in Rushdie. He recognises that the past cannot be fully recaptured. As a writer reflecting on the past, he can only “create fictions, not actual cities or villages, but invisible ones, imaginary homelands, Indias of the mind” (Rushdie 10). He further states that any attempt to recapture the past involves “broken mirrors, some of whose fragments have been irretrievably lost” (Rushdie 11).

The ‘home’ concept is a contested terrain in both postcolonial and diasporic narratives. Writers like Kamala Wijeratne and Carl Muller engaged with internal conflicts within Sri Lanka. Their writings translate to challenging traditional understandings of belonging and exploring concepts of home beyond physical boundaries. This contrasts diasporic voices such as Michael Ondaatje steering across the psychological and emotional complexities of creating new homes, albeit battling nostalgia and loss.

Both postcolonial and diasporic writers experiment with language. They incorporate multilingualism and diverse cultural references into their narratives. For instance, authors such as Nihal de Silva and Anne Ranasinghe employed language to subvert colonial power structures and reclaim their own voices. Ondaatje reflected on the linguistic landscapes of his transnational experiences.

Both postcolonial and diasporic writers can be seen as a cult that aims to disrupt dominant narratives imposed by colonial forces. Sri Lankan literature challenges simplistic representations of the island nation. Diasporic voices counter stereotypical portrayals of marginalised communities.

Transformative phases

The events of 1956 and 1972 significantly impacted Sri Lankan literature, intertwining with the themes of postcoloniality and diaspora discussed earlier. The Sinhala Only Act in 1956 mandated Sinhala as the sole official language, triggering tensions with Tamil minorities. This linguistic shift influenced themes of marginalisation and contested belonging in literary works. Writers like Anne Ranasinghe and Carl Muller explored the anxieties and power dynamics surrounding language within Sri Lanka, reflecting the struggle for a unified national identity amidst linguistic diversity. Some writers utilised Sinhala and English to challenge the imposed monolingualism and advocate for inclusivity.

Sri Lanka becoming a republic in 1972 paved the way for national identity and postcolonial self-determination debates. Writers entertained questions of decolonisation, cultural revival, and the impact of historical legacies more than they used to. They examined the complexities of forging a Sri Lankan identity distinct from colonial influences and internal ethnic divisions.

The interplay between the language shift, the transition to a republic, and the ongoing postcolonial and diasporic realities created a fertile ground for diverse literary responses. Selvadurai, for example, directly addresses the conflicts arising from the language policy and its impact on marginalised communities. Others, like Ashok Ferrey, explored the broader anxieties surrounding national identity and cultural preservation in the aftermath of becoming a republic.