If anyone visiting the Galle City this January needed a reality check on the extent of the island’s recovery after its crippling 2022 crisis, the thambili [king coconut] offered it. The popular thirst quencher that would have cost a few dozens of rupees a couple of years ago, is now priced at around Rs. 200 (approx. INR 50).

“Is anything reasonably priced in this country now?” the middle-aged seller asks me, shutting down any bargaining attempt. While scores of citizens like him grapple with the after-effects of dramatic inflation, the country is desperate to welcome more tourists this year to boost its foreign exchange reserves.

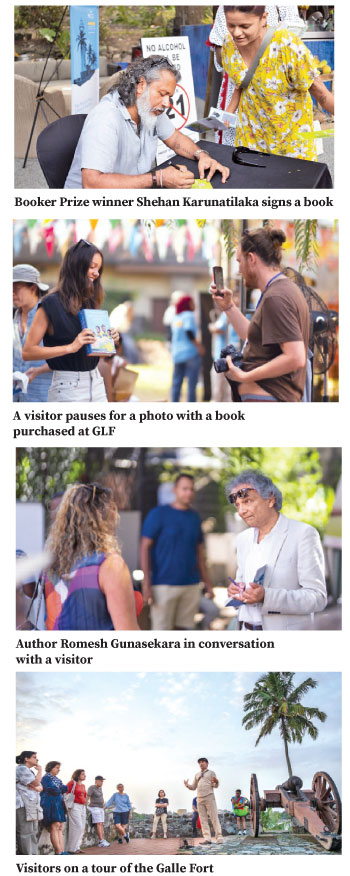

The Galle Literary Festival (GLF), held from January 25 to 28 in the charming city located on Sri Lanka’s southwestern coast, drew many visitors who had missed both the country’s calming beaches and its vibrant literary scene. Sri Lanka’s popular destination literary festival signalled an openness to spotlighting sensitive issues of the day.

Booker Prize

The timing got even better with Sri Lankan writer Shehan Karunatilaka winning the coveted Booker Prize in 2022. The award brought much-needed cheer to a country reeling under a crushing financial meltdown, while turning the international spotlight on Sri Lankan writing again.

“Galle Fort is alive, the sun is out, and we have been having very stimulating conversations,” says Karunatilaka, who attended the festival that has resumed after a break, owing to the Covid-19 pandemic and Sri Lanka’s economic crisis.

“What a turbulent history we have had in the last few years… the constitutional crisis [2018], Easter Sunday attacks [2019], the Covid pandemic, then the economic collapse and everything that followed. I think this is a positive sign that Sri Lanka is slowly rebuilding, but there is a lot of rebuilding to be done,” he says.

The centuries-old — and delightfully functional — Fort City and its ramparts had scores of tourists, both foreign and local, during the weekend of the Galle Literary Festival. While some visitors were busy session-hopping, others were simply walking around, as one does around Galle Fort, taking frequent gelato breaks and even more frequent selfies. Among the visitors was President Ranil Wickremesinghe.

Built by the Portuguese in the 16th century, and fortified by the Dutch in the 17th century — they preceded British colonialism on the island — the Galle Fort has remained a favourite tourist hotspot. In this cozy city Down South, Sri Lanka’s colonial history, a diehard Sinhala-Buddhist nationalist political base, and foreign visitors co-exist peacefully, in the confines of their bubbles. In its eclectic itinerary, this edition of the festival sought to showcase the island’s history, not only in the literary space, but also in food and the arts, featuring prominent speakers from the region and elsewhere.

Notably, it included screenings of films on themes such as mass graves in Sri Lanka, and the people’s movement that dislodged President Gotabaya Rajapaksa in 2022, signalling the event’s openness to featuring politically sensitive topics, in its ambit of prose, verse, food, heritage and art trails.

In a powerful collaboration, local theatre groups Mind Adventures and Stages presented Letters from Gaza in a poetry reading session, reminding the audience of the most compelling humanitarian question of our times.

In a powerful collaboration, local theatre groups Mind Adventures and Stages presented Letters from Gaza in a poetry reading session, reminding the audience of the most compelling humanitarian question of our times.

Putting together a literary festival, that too after a break, is not easy. Many from the past organising teams — the GLF began in 2007 — have moved on and some of the key partners and sponsors are no more involved, says festival director Giselle Harding.

Excited

“But we are not starting from scratch on all fronts. We know we have a fabulous reputation and people are very excited to have us back.” It is the “best of both worlds”, in her view, as the festival, while retaining a captive audience, is also drawing new voices.

For many participants, it was heartening to see their favourite ‘GLF’ bounce back. That weekend, the best-known heritage and boutique hotels inside the Fort were fully booked, and the restaurants teemed with people.

“I see this edition as a new beginning after the break stalled the festival’s momentum. Each literary festival is unique and as far as GLF is concerned, the location adds so much character — there are so many venues within and around the Fort that come alive with various events,” says Ameena Hussein, writer and co-founder of the Colombo-based Perera Hussein Publishing House.

Having been to literature festivals in Pakistan, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia, Hussein says the ability of these events to foster a sense of community is what makes it special for her. “I also notice differences in how readers in Lahore, for instance, have a stronger connection with literature in their vernacular as well,” she says, while observing that in Sri Lanka, the readership for literature in English and other languages does not necessarily overlap.

That is perhaps why some authors are making a case for further diversifying voices at the festival. British Sri Lankan author Romesh Gunesekera and Karunatilaka underscored the need for more translations of works in Sinhala and Tamil, in the final panel discussion of the festival, moderated by Hussain.

“We do not read enough of each other,” Karunatilaka says. Weighing in on the pressures faced by writers in the region, he says: “South Asian writers do not take freedom of expression for granted.” There is a degree of self-censorship in some contexts, but authors navigate that, often hiding behind characters and plots in fiction, they say.

All the same, some caution becomes necessary. “I’d rather keep writing than have a knife come at me,” Karunatilaka said.

Pictures by Meera Srinivasan/GLF/PMD

(The Hindu) [email protected]

President Wickremesinghe with visitors and stall holders at GLF