Travelling is not everyone’s cup of tea. Reasons can vary. It incurs expenses, for one. Some of us can’t get ourselves to move around at least for 500 metres. Especially the contemporary human is largely marked as couch potatoes thanks to those gadgets that stay faithful to us wherever we go. These technological comforts can make the very idea of moving about less appealing.

The world is rich with wonders and adventures, and exploring it can offer profound rewards and enrich our lives in ways that staying put cannot. Sometimes it’s time that we should have had a Hamlet to remind about those more things in heaven and earth than dreamt of in our sedentary lifestyles.

The world is rich with wonders and adventures, and exploring it can offer profound rewards and enrich our lives in ways that staying put cannot. Sometimes it’s time that we should have had a Hamlet to remind about those more things in heaven and earth than dreamt of in our sedentary lifestyles.

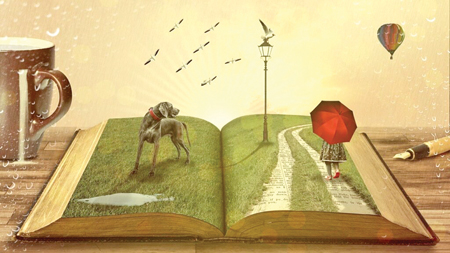

That’s where travel literature fits in.

New experience

Travel literature offers a passport to new experiences, all without leaving our armchair. This genre can include a variety of writing styles: from thrilling adventure to introspective memoirs.

Travel writing is a melting pot of essays, dedicated for collections or magazine features. Authors paint graphic scenes with words, taking readers to new landscapes, crowded cities, and ancient ruins. These descriptions make us explore the world as the very proxy of the writer who gets to experience different cultures and customs first hand. That said, travel reflects human movement across time and space. It allows us to see the world through the eyes of another: a peek into various historical periods and faraway lands.

Detailed descriptions of a destination’s attractions can spark the wanderlust in readers, inspiring them to embark on their own journeys. Beyond scenic descriptions, travel literature explores the nuances of language, the explosion of flavors in local cuisine, the intricacies of political systems, and the everyday routines of different people.

Detailed descriptions of a destination’s attractions can spark the wanderlust in readers, inspiring them to embark on their own journeys. Beyond scenic descriptions, travel literature explores the nuances of language, the explosion of flavors in local cuisine, the intricacies of political systems, and the everyday routines of different people.

Capturing the essence of a place in words is no walk in the park. Any author must have adequate skills to convey the sights, sounds, smells, and even tastes of a destination. They are the signposts that lead the reader to the warmth or wariness of the local people as well as the architectural wonders that define a location.

The genre has a rich and lengthy history behind it. The early travel writers were typically wealthy, educated men who had the means to travel and were encouraged by their education to explore. They viewed the world from a colonial perspective, often downplaying the significance of the cultures and peoples they encountered in their writings. Postcolonial writers recognised the ethical issues with this approach and endeavoured to present a more balanced and sensitive portrayal of other people, cultures, places, and histories. However, for many years thereafter, travel writing primarily served as practical destination guides rather than literary works.

Travel writing holds significance because it brings a human perspective to distant places. Unlike conventional journalism, it doesn’t strive for detached objectivity or rely on sensationalized narratives driven by the twenty-four-hour news cycle’s focus on wars and disasters. Instead, it adopts a personal approach to explore the chores of daily life in unfamiliar territories.

Throughout history, one of humanity’s oldest and most enduring narratives is that of the wanderer who ventures away from home, confronts the mysteries of the unfamiliar, and ultimately returns to share their experiences. From ancient epics like the Epic of Gilgamesh to the fantastical realms depicted in fictional works such as Oz, Narnia, or Westeros, travel has consistently served as a literary device that ignites struggle, growth, and transformation.

Throughout history, one of humanity’s oldest and most enduring narratives is that of the wanderer who ventures away from home, confronts the mysteries of the unfamiliar, and ultimately returns to share their experiences. From ancient epics like the Epic of Gilgamesh to the fantastical realms depicted in fictional works such as Oz, Narnia, or Westeros, travel has consistently served as a literary device that ignites struggle, growth, and transformation.

Many of the conventions we still associate with the genre trace back at least as far as Herodotus’s Histories. Herodotus employed firsthand inquiry and reporting to offer (albeit imperfect) insights into Near Eastern cultures for a Greek audience. For over two millennia, from figures like Zhang Qian and Ibn Battuta to the intrepid explorers of the British Empire, the implicit aim of travel writing was to depict the customs and peculiarities of distant peoples and places. Travel writing had a profound influence not only on exploration, science, and commerce, but also on the development of ideas and literature.

Trade routes

Early forms of travel literature emerged around the 2nd century CE, with works like the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. It provides detailed accounts of trade routes. Pausanias’ “Description of Greece” offers a geographical and cultural guide to the ancient world. Travel journals penned by figures like Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta chronicled their journeys extraordinaire across continents.

In China, travel literature flourished during the Song dynasty, where it was known as travel record literature. The experiences documented by writers such as Fan Chengda and Xu Xiake include geographical and topographical information in meticulous detail. This approach encompasses narratives, prose, essays, and even diaries. These detailed accounts provide insights into destinations like 13th-century Cambodia.

Interestingly, one of the earliest documented instances of travel for pleasure and subsequent writing about it comes from 14th century Europe. In 1336, Petrarch, an Italian scholar of fame, undertook the visibly odd task of climbing Mont Ventoux. Unlike his companions perched at the base, Petrarch was acutely motivated to reach the summit. His curiosity and appreciation for the experience contrasted sharply with the indifference of his fellow travellers.

Of course, Petrarch documented his ascentlater as a narrative. He drew allegorical comparisons between the physical challenge of climbing the mountain and his own personal moral development. This narrative perhaps demonstrates the nascent stage of travel for pleasure as well as travel writing. Petrarch’s narrative also has a potential for travel experiences to spark introspection and philosophical contemplation.

Of course, Petrarch documented his ascentlater as a narrative. He drew allegorical comparisons between the physical challenge of climbing the mountain and his own personal moral development. This narrative perhaps demonstrates the nascent stage of travel for pleasure as well as travel writing. Petrarch’s narrative also has a potential for travel experiences to spark introspection and philosophical contemplation.

Michault Taillevent is a poet employed by the Duke of Burgundy who journeyed through the Jura Mountains in 1430. He documented his personal thoughts which include startled reaction to the steep rock faces, and the alarming roaring of mountain streams. Antoine de la Sale (circa 1388 – circa 1462), the author of Petit Jehan de Saintre, ascended to the crater of a volcano in the Lipari Islands in 1407, leaving behind his impressions. He cited “gatherings of reckless youth” as his stated motivations for the journey.

Indian inquiry

By the 16th century, accounts of voyages to India and Persia became frequent enough to be compiled into collections such as the Novus Orbis (“New World”) by Simon Grynaeus, and collections by Ramusio and Richard Hakluyt. Travellers to Persia in the 16th century included the brothers Robert Shirley and Anthony Shirley, while those journeying to India included Duarte Barbosa, Ralph Fitch, Ludovico di Varthema, Cesare Federici, and Jan Huyghen van Linschoten. Humanist travelers in Europe also authored accounts, often detailing monuments and inscriptions, such as Seyfried Rybisch’s Itinerarium (1570s), Michel de Montaigne’s Journal de voyage (1581), Germain Audebert’s Voyage d’Italie (1585), and Aernout van Buchel’s Iter Italicum (1587–1588).

In the 18th century, writings about travel were widely referred to as “books of travels,” predominantly comprising maritime journals. In 18th-century Britain, travel literature enjoyed immense popularity, with nearly every renowned writer dabbling in this genre; for instance, Gulliver’s Travels (1726) serves as a social critique modeled after such accounts, while Captain James Cook’s diaries (1784) rivalled contemporary best-sellers. Alexander von Humboldt’s Personal narrative of travels to the equinoctial regions of America, spanning the years 1799–1804, initially published in French, underwent translations into various languages and left a profound impact on subsequent naturalists, including Charles Darwin.

Accounts of the Grand Tour emerged as notable examples of travel literature: aristocrats, clergy, and affluent individuals with ample leisure time ventured across Europe to acquaint themselves with its art and architectural heritage. Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894) stands as a trailblazer in tourism literature with works like An Inland Voyage (1878) and Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes (1879), recounting his expeditions in the Cévennes region of France. These works are among the earliest popular publications to depict hiking and camping as recreational pursuits, even detailing his commissioning of one of the earliest sleeping bags.

In the 19th century, notable figures in travel literature included the Russian Ivan Goncharov, who penned his experiences of a global voyage aboard the Frigate “Pallada” (1858), and Lafcadio Hearn, renowned for his insightful and sensitive portrayal of Japanese culture.

In the 19th century, notable figures in travel literature included the Russian Ivan Goncharov, who penned his experiences of a global voyage aboard the Frigate “Pallada” (1858), and Lafcadio Hearn, renowned for his insightful and sensitive portrayal of Japanese culture.

The interwar period of the 20th century is often hailed as a golden age of travel literature, marked by the journeys and writings of esteemed authors such as Graham Greene, Robert Byron, Rebecca West, Freya Stark, Peter Fleming, and Evelyn Waugh.

Towards the latter part of the 20th century, there was a notable surge in the popularity of travel writing, particularly within the English-speaking world. Writers like Bruce Chatwin, Paul Theroux, Jonathan Raban, Colin Thubron, and others contributed significantly to this trend. While previously, travel writing primarily attracted attention from historians and biographers, it gradually evolved into an academic discipline in its own right, with critical studies of travel literature gaining prominence.

Modern travel literature

Today, travel literature has evolved into a sophisticated art form, extending beyond mere descriptions of road trips and destinations.

Facebook and YouTube are a classic case in point where modern travel literature fits in. Albeit oftentimes mindless scrolling, these social media offer us a plethora of travel literature in advanced forms: visual and motion. Authors of that literature no longer need to vex over words. The photographs and videos do the job by speaking for which 1000 words would have been written.

And then there are ‘creatives’ (those small boxes appear somewhere in a corner of our screen) enticing us with alternative destinations to the ones we’ve been searching for. Technology’s constant evolution has a name for it: algorithm update. These algorithms analyse our browsing history and preferences to suggest alternative travel destinations.

Not every writer can become a travel writer. But any reader can become a travel reader. The reason is obvious: travel literature transcends mere descriptions of destinations. It is the window that bridges the writer and the reader.