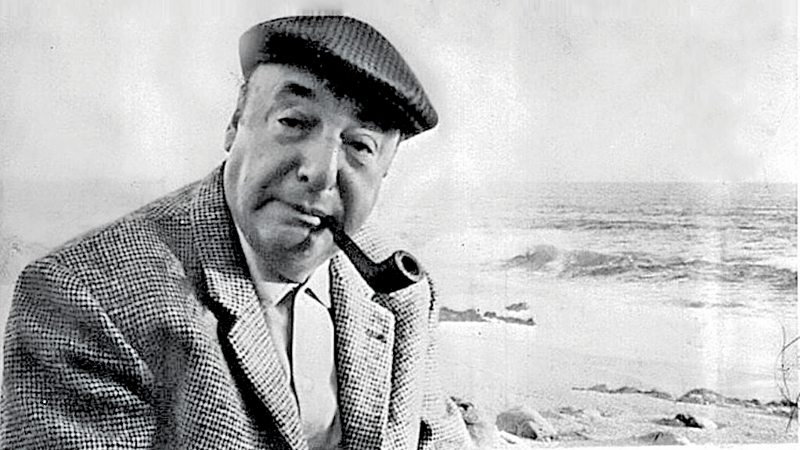

In the diverse landscape of literary history, few poets evoke the same level of passion and controversy as Pablo Neruda. Recently, I had the unique opportunity to engage in an interesting conversation with Eda Cleary, a Chilean-Irish sociologist and devoted scholar of Neruda’s life and works.

In the diverse landscape of literary history, few poets evoke the same level of passion and controversy as Pablo Neruda. Recently, I had the unique opportunity to engage in an interesting conversation with Eda Cleary, a Chilean-Irish sociologist and devoted scholar of Neruda’s life and works.

Eda’s deep insights are contained in her two essays, “Ceylon in the Heart of Pablo Neruda” and “Josie Bliss: Pablo Neruda’s Burmese Lover After 88 Years,” both published in esteemed journals like Letralia and Le Monde Diplomatique in Spanish and English. Her journey to Sri Lanka was not merely an academic pursuit; it was a heartfelt mission to connect with the acclaimed filmmaker Asoka Handagama, whose film “Alborada”, a beautiful cinematic expression of Neruda’s life during his time in the former Ceylon.

Invited to join this enriching conversation by Handagama himself, I found Eda’s vibrant intellect and passionate exploration of Neruda’s artistic journey truly inspiring. In a couple of hours, a long conversation with Eda flowed through the depths of Neruda’s poetic legacy, touching on themes of love, admiration, and the complexities that framed his life. This article seeks to convey the essence of our enlightening exchange while illuminating Eda Cleary’s significant research discoveries about one of the world’s most celebrated poets.

Exotic Asia

Eda Cleary

It is a well-known fact that Asia has been regarded as one of the most exotic and mystical regions by the rest of the world. Through reading Neruda’s memoir and some of his poetry, this notion becomes evident. In my conversation with Eda, she explained the fascinating exploration of Pablo Neruda’s complex relationship with Asia, particularly as reflected in his fascination with Josie Bliss, an indigenous woman from Mandalay. According to Eda, Latin Americans “dreamed about being in Asia,” where women like Bliss were seen as symbols of freedom and sexuality, able to dance and express themselves without fear of punishment. This stood in stark contrast to the realities faced by many in Chile, a country marked by underdevelopment and harsh winters, where Neruda’s works resonated deeply with a population yearning for escape and inspiration. Eda notes that Neruda transformed the literary landscape, enabling a newfound appreciation for Latin American women, particularly those of indigenous descent, who had been largely ignored in favour of “white women with blue eyes.”

As a sociologist, Eda emphasises Neruda’s innovative approach to capturing the complexities of identity and culture, suggesting that his nostalgia for Asia and his relationship with figures like Josie Bliss reflect an inner conflict. “He was totally divided about his feelings on Asia,” Eda asserts, pointing to the profound impact of his experiences in Sri Lanka during his late twenties. While Neruda’s poetry celebrated a raw and vibrant creativity during his time in Asia, his later political commitments, particularly his alignment with communism, constrained this freedom. Eda contrasts Neruda’s experiences with those of contemporaries like Octavio Paz, who approached Indian culture with reverence, highlighting Neruda’s more tumultuous personal life. “Neruda was somebody who loved evil,” she observes, suggesting that his public persona often masked deeper contradictions within his character. Ultimately, Eda posits that Neruda’s “Residence on Earth” remains his most significant work, capturing the exuberance of his early experiences while reflecting the complexities of his later life marked by political dissension and emotional turmoil.

Controversy

In Chile, extensive research has been conducted on Pablo Neruda, a poet celebrated in his homeland, a contrast to many world-renowned artists who lack recognition in their own countries. Known for his controversial persona, Neruda’s life is marred by an incident involving the sexual assault of a “Coolie” girl during his stay in Sri Lanka, which has drawn significant criticism. Eda said, “The Chileans are delighted with Neruda. But the feminists, especially the Chilean feminists, were outraged when they learned about the assault on the ‘Coolie’ girl. They began fighting against the glorification of Neruda.” This backlash caused a significant crisis for the Neruda Foundation, which relies on tourism from the poet’s various museums, including Isla Negra, La Sebastiana, and La Chascona. Eda said, “Thousands of people come to Chile specifically to visit these sites,” highlighting Neruda’s continued appeal despite the controversies.

However, she anticipates difficulty in writing her third essay, which will delve into Neruda’s “evil deeds,” particularly regarding his first wife, María Antonia. Eda pointed out, “This woman was fascinating yet ultimately destroyed by the Chilean artistic community,” and noted that Neruda deliberately undermined her image. She believes that while Neruda’s poetic legacy cannot be diminished, it is vital to confront the complexities of his character. “You can never idolise someone; we must acknowledge our weaknesses and the controversial aspects of our lives,” Eda asserted. She expressed her concerns about how Neruda’s legacy is presented, stating, “We cannot tell future generations that he was the greatest artist Chile ever had.” Despite receiving criticism for her stance, Eda maintains, “Understanding someone fully allows us to accept them better without judgment.” She said that Neruda faced moral scrutiny during his lifetime, having been involved in questionable activities supported by archival evidence and letters. Eda emphasised that while Neruda was a master of public relations and innovation during his time, it was not Europe but Asia that contributed significantly to his fame, stating, “His political writings were born from the very essence of daily life.”

Neruda’s legacy

Eda Cleary with Asoka Handagama

Discovering life is an ongoing journey, especially when you’re young,” Eda said, reflecting on Pablo Neruda’s poetic exploration of the world. She cited a line from one of his poems, noting, “I didn’t know that the world existed before I came to Asia.” Eda emphasized that to truly understand such sentiments, one must have been in Asia, as “ordinary Chileans may struggle to grasp the depth of that experience.” She elaborated on Neruda’s poignant expression of vulnerability with the phrase, “No tenía zapatos,” meaning “I didn’t have shoes.” To Eda, this conveyed a sense of nakedness, a return to the essence of being, reminiscent of how one enters the world. “He expressed a profound authenticity in his work,” she commented, highlighting her admiration for his unique approach to life and literature.

Eda voiced concern over the dominance of Western perspectives in literary discussions, stating, “We should focus on what we know; our own experiences should shape our narratives.” She recognized Neruda’s exceptional talent but lamented the constraints of his Chilean identity and the perspectives he brought back from his time in colonial Burma. “He had a significant vision of the world, touching on themes like colonialism and authoritarianism,” she said. Although she acknowledged Neruda’s universal appeal, Eda noted that his ideological stance may have limited his influence over time. “As the world evolves, figures like George Orwell are becoming increasingly relevant,” she said, suggesting that Neruda’s works, while poetically significant, may wane in meaning due to their heavy ideological focus. She specifically referenced “El Canto General,” stating, “It’s a fascinating epic that tells the story of Latin America, but it’s too ideological,” and added, “It’s not the same as ‘Residencia en la Tierra.’ Eda expressed her need to explore these complexities in her writing: “Why should I write another essay about him? Because it’s important to uncover what really happened.”

Anthropological viewpoint

When discussing the anthropological aspect of how Europeans view Asia, Eda had some insightful observations. She referenced Edward Said, a Palestinian academic, stating, “I don’t know if you are familiar with his fantastic book, Orientalism. I learned a lot from him because Arab countries are often perceived as Oriental people.” Eda elaborated on this idea, explaining that to Westerners, “the concept of the Oriental implies they are not rational; they are seen as purely passionate and sentimental, clinging to traditions, superstitions, and open sexuality.” She emphasized that, according to Said, “the East is viewed as more closely aligned with nature rather than culture,” which Westerners often reduce to a mere collection of customs and religions.

Eda criticised the Western perception of identity, noting, “They believe their identity is shaped by Christian, Buddhist, Hindu, or indigenous traditions, and they consider these Eastern traditions to be of lower value because they see themselves as more observant.” She said that this colonial view has permeated the entire academic world, categorising people in terms of Orientalism.

Drawing from her own experiences, she shared, “During my sociology studies in Germany, it struck me as unusual. Many go there to study engineering or history, yet a German can travel to Latin America for just five days and come back as an expert.”

Eda said, “After World War II, Germany propagated the idea that it had no social classes and that everyone understood each other. However, when foreigners arrived to fill labour shortages, the reality was starkly different; they found themselves at the bottom of the social hierarchy.” She argued that, like the Germans, Chileans are also affected by the ideologies created by Western scholars, explaining that “we are also orientalist if we think about Latin America solely in terms of guerrillas, wild forests, and people dancing salsa and mambo. This perspective is completely misguided.”

To Eda, understanding this issue is crucial. “We need to recognise that this view is not limited to Westerners; we often perceive ourselves in similar, reductive ways. Overcoming this mindset is a significant task.” She pointed out the irony in how identity is often oversimplified. “For example, you are dark-skinned, I am white-skinned, yet we belong to societies considered to be at the lower end of the global hierarchy.” She lamented the lack of nuance in these perceptions, highlighting that many Europeans now show a genuine interest in Latin America, attracted to its lifestyle.

Eda expressed her identification with Said, stating, “I relate to him; I often feel out of place, and unfortunately, he has passed away. Neruda, too, exhibited a somewhat orientalist viewpoint regarding Asian people.”

Eda has been dedicated to her research for five years, with a particular focus on Burma, which she found highly interesting. After her time in Burma, she travelled to Salem and then continued her journey to Jakarta, Java. Throughout her research, she has published two essays in notable outlets such as Le Monde Diplomatique, El Mostrador, and Escritores.org. Additionally, Eda has been in contact with Adam Feinstein, an English-speaking biographer of Pablo Neruda, and has corresponded with David Shetlovsky, who generously sent her his works to support her research.

Emancipation of women during dictatorships

It was truly an insightful couple of hours of conversation, which is quite hard to summarise. To conclude the article, I would like to mention Eda’s interesting thesis, which she completed for her PhD. “I earned my PhD with the highest mark from my generation,” she explained, “because I wrote about the emancipation of women during dictatorships.” Her thesis posited that women, accustomed to authoritarian structures within their families, are often “intricate.” She elaborated, “They can hide their feelings to survive and organise behind the scenes.” Eda acknowledged the controversy surrounding her findings: “Many people were offended by the idea that women are intricate, which is deemed unacceptable. Yet, intrigue is a very human phenomenon, especially when opportunities are limited under patriarchal domination.”

Describing the resilience of women in Chile, she stated, “It was the women who organised the resistance against the dictatorship, but they did so not as individual leaders but as the unnamed relatives of men.” Eda lamented that the names of these courageous women, who fought for justice for disappeared political prisoners, have largely been forgotten. “After we regained democracy, these women became lost in the political landscape because they had not been prepared to engage with democratic instruments. They did not know how to confront political adversaries face-to-face or propose strategies.”

Eda expressed pride in her work, noting, “My research was published in Germany and has been widely cited there. I later translated it into Spanish for specialised gender studies, making it unique in this context.” Her thesis reflects a groundbreaking approach to understanding women’s roles in historical and political movements, emphasising their vital contributions during tumultuous times.

I truly had an amazing few hours with Eda Cleary, whose million-dollar smile always shines brightly. She spoke effortlessly about her findings on Neruda, which is her passion project. To conclude this article, I would like to quote the last paragraph of her essay, “Ceylon in the Heart of Pablo Neruda.”

“Ceylon was a crucial place for Neruda’s development as both a poet and a man of the world. His stay in the East was determined by his remarkable free-thinking determination and willingness to participate in the official and artistic activities of the social circles that surrounded him. It can be said that Neruda’s “solitude” in Ceylon was probably “literary” and that the East had a significant influence on his work.

His stay in Ceylon was a true window to the world, from which an important network of opportunities for international dissemination of his poetry would be forged in the future. There he was enriched by a rich cultural world that combined various branches of art, emphasizing the combination of cultures inherited from the colonies and those of the native peoples. Ceylon, “the most beautiful large island in the world,” forever inhabited Neruda’s heart , and today his poetry beats strongly in the world of Ceylon’s letters.”