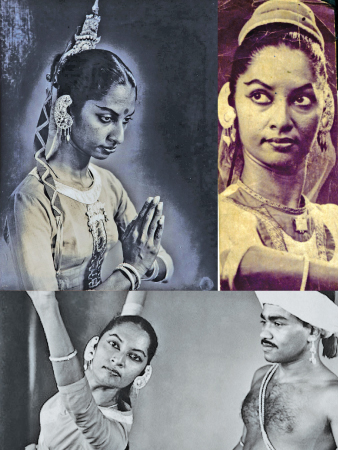

Sri Lankan traditional dance exponent Vajira Chitrasena passed away at the age of 92 on September 23. She was one of the country’s prominent figures in traditional dance, playing the roles of a Kandyan dancer, choreographer and teacher. Together with her husband, the legendary Chitrasena, Vajira spearheaded the traditional dance scene in Sri Lanka. Here we pay tribute to this fine performer who is known as Sri Lanka’s first prima ballerina or the grand dame of dance.

Vajira entered the local dance scene at an age when this dance form was traditionally performed only by males. Svelte and lithe in figure and sinuous and lyrical in her movements she was soon able to master the art and take it to a whole new level by setting the tone for women to become ritual dancers. It is no wonder Vajira is regarded as the best female dancer to emerge in Sri Lanka – second only to Chandralekha.

Born in 1932, Vajira owes a great deal to her mother Lilian, who had a gift for grace. Dancing ran in the family because, besides excelling in other sectors, Vajira’s sisters were all dancers. Since she noted her daughter’s exceptional gift early, Lilian sent Vajira to Sri Palee in Horana, which was modelled after the renowned Santiniketan of Rabindranath Tagore in India. It was through this exceptional talent for dancing that she encountered the legendary dancer and dance guru, Chitrasena, who had come to deliver a performance at the Kalutara hall. It was inevitable that they would connect because both of them shared a passion for dancing. She was also someone whom he could bank on to carry on his work of taking traditional Sri Lankan dance forms to the world.

Born in 1932, Vajira owes a great deal to her mother Lilian, who had a gift for grace. Dancing ran in the family because, besides excelling in other sectors, Vajira’s sisters were all dancers. Since she noted her daughter’s exceptional gift early, Lilian sent Vajira to Sri Palee in Horana, which was modelled after the renowned Santiniketan of Rabindranath Tagore in India. It was through this exceptional talent for dancing that she encountered the legendary dancer and dance guru, Chitrasena, who had come to deliver a performance at the Kalutara hall. It was inevitable that they would connect because both of them shared a passion for dancing. She was also someone whom he could bank on to carry on his work of taking traditional Sri Lankan dance forms to the world.

“We completed every task together. ‘Karadiya’ was his principal ballet after years of experimentation. We travelled all over the world, including Russia, with ‘Karadiya’. Chitrasena accomplished a great deal, and my assistance made it possible. I carry on Chitrasena’s work. He brought ritual dance to the performance area. He encountered gurus and picked up ceremonial dances in the villages. His father staged plays at Tower Hall and was also involved in theatre. Being creative ran in the family. Chitrasena absorbed all those things as a child. Once he got back from his dance training in India, he introduced modern theatre props like lighting and costumes for the stage,” Vajira once recalled how she had grown as a dancer and choreographer due to the influence of Chitrasena, whom she married when she was 18.

Her first children’s ballet,’Kumudini’

Once she rose to prominence within Chitrasena’s dance company, she began to express herself creatively. In 1952, at the age of 19, she performed in her first children’s ballet, ‘Kumudini’, set to a song by Ananda Samarakoon. Thereafter, a new creation appeared roughly every two years. Her primary contribution to dance was learning how to choreograph dances and perform children’s ballets, which was relatively uncommon in Sri Lanka then. In addition, she went on to become the nation’s first female professional dancer. Others had danced before her, but they didn’t take dance as a serious subject. Thus it was Vajira who pioneered the woman’s version of the Kandyan dance. This was especially seen in how she infused femininity into the Gajaga Vannama, a performance that paid homage to the elephant and was typically associated with men. This modification was hailed as revolutionary since it gave female dancers a voice in a field that had previously denied them one.

Kandyan dancing

Once when she was queried about how she developed a feminine touch to Kandyan dancing Vajira added that years of consistent dancing are necessary to gain that experience. Anything that has been polished for years must eventually show some wear and tear. Therefore, the feminine style evolved through her and Chitrasena invented ballet and the narrative that goes with it through theatre. Meaningless dance moves prevailed before this.

Once when she was queried about how she developed a feminine touch to Kandyan dancing Vajira added that years of consistent dancing are necessary to gain that experience. Anything that has been polished for years must eventually show some wear and tear. Therefore, the feminine style evolved through her and Chitrasena invented ballet and the narrative that goes with it through theatre. Meaningless dance moves prevailed before this.

When anything new is introduced, there are naturally those who oppose or criticise the aspect. This happened to Vajira too. Some accused her of copying the West when she was performing the swan dance in ‘Nala Damayanthi’. However, all these allegations were put to rest when Swan Lake’s Australian critic discovered that it had Eastern roots rather than being a mere mimic of the West. This uniqueness was developed by Vajira by creating a set of exercises to dissect Kandyan dance movements that could be used to train dancers, drawing on her limited exposure to other dance traditions, such as classical ballet during tours to Eastern Europe, the West, and Australia, or modern dance when artistes like Martha Graham visited the island in 1956.

In addition to ensuring improved consistency and clarity in lines and stances, these exercises greatly facilitated the teaching and learning processes. By doing this, she also increased the range of motion. For example, she added floor exercises to the standing and kneeling routines, whereas the ritual form does not allow for any movement when the dancer is lying on the ground.

Vajira had earlier said that her creative side has always been highlighted in everything that she does. She has always had this creative side to her. No matter the day or age, it will grow given the right nutrition. However, Vajira believes that when it comes to promoting moral principles, things have changed since then. She maintained that due to the influence of the media, many stoop to the level of copying cheap dance forms off programs they see and presenting them on a stage to win rave reviews. She noted that mere hip-wriggling movements do not make up dancing. Rather you need to dive deep into the subject to excel as a choreographer and create anything on stage instead of following trends.

She and Chitrasena collaborated to produce works that combined innovation and tradition. Their performances, such as ‘Karadiya’ and ‘Nala Damayanthi’, engaged audiences deeply, told stories, and evoked strong feelings in addition to showcasing the grace of the dance form. These shows were where Vajira’s talent as a choreographer really came through. Her command of movement, rhythm, and narrative turned the stage into a magical setting.

Graceful

As the principal dancer for the Chitrasena Company, Vajira performed throughout nearly every nation on earth, including most of Europe, Canada, Japan, Britain, India, Russia and Australia. Presidents, Prime Ministers, ambassadors, religious leaders, celebrities, and members of the royal family have all seen and applauded her dancing abilities. In reality, there was nothing more left for her to accomplish because the self-control, promise, unique grace and purity of line of this peerless dancer were evident until the very end. Today her daughters Upeka de Silva and Anjalika Melvani, and granddaughters Thaji Dias, Heshma Wignaraja and Umadanthi Dias all bear the honour and responsibility of carrying the tradition of Sri Lankan traditional dance forward.

Vajira received the esteemed “Padma Shri Award,” one of the greatest civilian honours in India, on January 26, 2020. She was also granted the title of “Deshabandu” in Sri Lathem. She will always live in the hearts of many a budding dancer or dance enthusiast as the premier female dancer who established standards for the stage and modelled morality for many young students to follow.