Two recent developments prompted me to write this “Thorns” column on passports. The first is the current impasse over the issue of passports due to several factors, some of which go all the way back to the economic crisis of 2022. This has especially affected those who are waiting to leave for employment abroad. The Government is now exploring the possibility of issuing e-passports.

Two recent developments prompted me to write this “Thorns” column on passports. The first is the current impasse over the issue of passports due to several factors, some of which go all the way back to the economic crisis of 2022. This has especially affected those who are waiting to leave for employment abroad. The Government is now exploring the possibility of issuing e-passports.

The other factor is the recent release of the Henley and Passport Index 2025, where Sri Lanka has again fared poorly, being placed at 96. We apparently have visa-free, e-visa or ETA access to only 44 countries, which is nothing to be proud of 76 years after gaining Independence. President Anura Kumara Dissanayake himself stressed the importance of climbing the passport ladder in his inaugural speech last year. Indeed, the Foreign Ministry must get cracking on this matter without delay. I have written on this topic many times previously.

New technologies

In this article, I want to focus on the concept of the paper-based passport itself and whether it will be a thing of the past in the next few decades thanks to the emergence of a slew of new technologies.

The Republic of Genoa (a medieval and early modern maritime republic from 1099 to 1797 in Liguria on the Northwestern Italian coast) is credited with issuing the first passports in the modern sense. In the 12th century, they issued a document called Bulletta to their nationals travelling to Genoese colonies and to foreigners entering their ports. However, the concept of travel documents dates back much further. For example, in ancient Persia, King Artaxerxes I issued a letter to Nehemiah, granting him safe passage to rebuild Jerusalem. This is considered the first recorded mention of the concept of a passport.

In more modern times, England is considered to have issued the first passport, which was a “Safe conduct” document granted by King Henry V in the 15th century. The earliest reference to these documents is in the Safe Conducts Act of 1414. Even today, most passports carry a message from the leader of the respective country to grant safe passage without let or hindrance to the holder.

However, the passport as we know it today is only over a century old. Following an agreement among the League of Nations, the precursor to the United Nations (UN), to begin standardising passports, the world’s first passport, dubbed “Old Blue,” was issued in 1920 by the UK. The League of Nations met in France where they specified the size, layout, and design of passports for 42 nations. The passport design was revised again in 1947.

The league expanded Old Blue into a 32-page document (now most countries have 64-page passports). In that initial book, the first four pages showed the owner’s facial characteristics, occupation, and the country of residence/address (these have since been condensed to one or two pages).

The passport layout also made some assumptions about the owner. The booklet included a box for the photograph of the spouse and space for the names of his children. This was included under the idea that each passport owner was a married male travelling with his wife and children.

The concept of the passport has not changed much all these years. We still need a passport to go to any other country, along with a visa (which can be paper-based or electronic) if required by that country. But the rapid evolution of technology has led some analysts to question whether paper passports can be done away with completely. Several airports around the world are already trialling some of these advanced technologies.

Almost all countries now issue Machine Readable Passports (MRPs) which can be easily scanned at immigration counters and self-service kiosks at airports. They are also called Biometric passports because they have fingerprints and other information stored on a chip or embedded in the paper itself. Still, at its core, it is a paper passport that one has to carry physically.

The concept of e-passports has also gained traction. These are traditional passports with embedded chips that store biographical information and digital signatures to prevent counterfeiting. While they still require a physical document, they offer enhanced security and convenience compared to older, normal passports.

Apart from the passport itself, there is one other device that we carry when we go abroad – the smartphone. I travelled widely within the US and Canada a couple of months ago, without ever showing a printed boarding pass or attraction ticket. They were all stored on my phone and I was waved through everywhere with just a scan of the phone.

By the same token, the phone can essentially store one’s passport information too. This is the idea behind Digital Travel Credentials (DTC) developed by the Montreal-based International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). DTC systems store passport information on a traveller’s smartphone and securely in the cloud. These systems use cryptographic methods to ensure authenticity and prevent forgery. These are also called Digital Passports.

With the rise of smartphones, many countries are exploring the use of mobile devices as travel documents. DTC and other apps can store digital versions of passports and other travel information, making it easier for travellers to manage their passport, visa and travel insurance documents. Blockchain technology too can be used to create a secure and tamper-proof digital identity that can be used for travel and other purposes.

With the rise of smartphones, many countries are exploring the use of mobile devices as travel documents. DTC and other apps can store digital versions of passports and other travel information, making it easier for travellers to manage their passport, visa and travel insurance documents. Blockchain technology too can be used to create a secure and tamper-proof digital identity that can be used for travel and other purposes.

Technologies such as facial recognition, fingerprint scanning, and iris recognition are being integrated into travel systems to verify identities quickly and accurately without needing a physical passport. Iris recognition technology scans the unique patterns in a person’s iris, offering a highly secure and accurate method of identification. It is also said to be less intrusive than facial recognition, which is used by law enforcement as well to nab criminals and suspects.

Airports in several countries are already conducting trials of passport-free travel systems using these biometric systems. Automated check-in kiosks, now standard at most airports, are evolving as airlines push towards more digital solutions. These self-service stations allow travellers to check in, select seats, print boarding passes, and tag bags without staff assistance.

Artificial Intelligence

Artificial Intelligence (AI) can be used in conjunction with these methods to enhance document verification processes, making it easier to detect fraudulent documents and streamline border control procedures. They can be accessed and verified digitally, eliminating the need for physical documents. The Covid-19 pandemic accelerated the development of non-contact biometric authentication to facilitate a more hygienic and seamless experience for passengers.

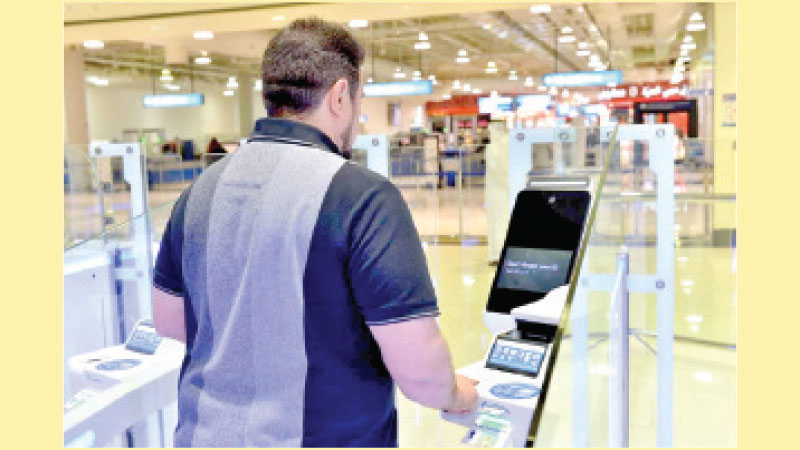

The Dubai International Airport (DXB) in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) already uses facial recognition technology to streamline immigration and security processes. The system uses cameras to capture facial images, which can be used for passport control and boarding. Under this system, passengers can use facial recognition to pass through gates without needing a paper boarding pass or passport. The system uses AI to recognise faces and irises. However, passengers must pre-register for the service. Passengers can save time in lines and board flights faster with this system.

This service is combined with “Smart Gates” which allow passengers to enter and exit the airport without ever seeing an immigration agent. There are plans to install such gates at the Bandaranaike International Airport (CMB) too. Oakland International Airport and Newark Liberty International Airport in the US have implemented biometric kiosks and self-boarding systems, to enhance passenger verification and streamline processes.

Biometric security screening, which uses facial recognition to verify traveller identities, is expanding rapidly across U.S. airports as part of the Transportation Security Administration’s (TSA) effort to enhance security and reduce wait times. The technology, which TSA began testing in 2019, can reduce security interaction time from 25 seconds to roughly 10 seconds. Amsterdam Airport Schiphol launched an Apple Watch app in January 2024, using AI and thousands of motion sensors to predict crowd sizes and wait times. The system uses smart, self-learning algorithms to make departure, transfer, and arrival processes more predictable for travellers, according to the airport.

Major airports are launching mobile apps such as these to provide real-time updates about flights, dining options, and parking to streamline the travel experience. Advancements in facial recognition, digital passports and biometric scanning, and AI-driven security checks will soon become commonplace within the airport setting, making the journey from check-in to boarding gate smoother and reducing passenger queuing time by an estimated 30-40 percent. In fact, airports around the world are investing in such technologies at a rapid pace. The global smart airports market, valued at US$ 18.2 billion in 2023, is projected to reach US$ 40.4 billion by 2030, according to Research and Markets.

A recent survey conducted in the US revealed that most passengers were in favour of ditching paper passports. “Confidence in biometric identification is on the rise,” states IATA’s 2023 Global Passenger Survey document. “In the past 12 months, 46 percent of passengers used biometrics at the airport, up from 34 percent in 2022. Seventy-five percent of passengers prefer using biometric data over traditional passports and boarding passes.”

This has another advantage – if you lose a paper passport, it could take months to get a new one due to the amount of red tape involved. On the other hand, a digital passport (and any electronic visa) “lives” in the cloud and there is no need to worry about losing your DTC. The passport could be in your phone and or smartwatch. All you do is scan it and go. However, legitimate concerns about data privacy and management must be addressed by Governments and airport authorities.

Birth Lottery

If all goes well, paper passports could disappear within the next two decades. But visas are a different question altogether.

Visas depend on the “Birth Lottery” – if you are born in Singapore, you automatically inherit the world’s best passport with visa free entry to 195 countries, but if you are born in bottom-placed Afghanistan, you can only visit 26 countries visa-free.

It might take around 200 years for the developing world to catch up to developed States, which is the only scenario that can eliminate visas as we know them. But the sooner they go the better – the world belongs to everyone, not just those from developed nations.