A little-known female author, G. Misihami’s spirit was very much present at a function held in Jaffna on January 18. A cultural centre in Jaffna was named after Thiruvalluvar, the author of Tirukkural – a classic popularly known in Tamil culture as Kural.

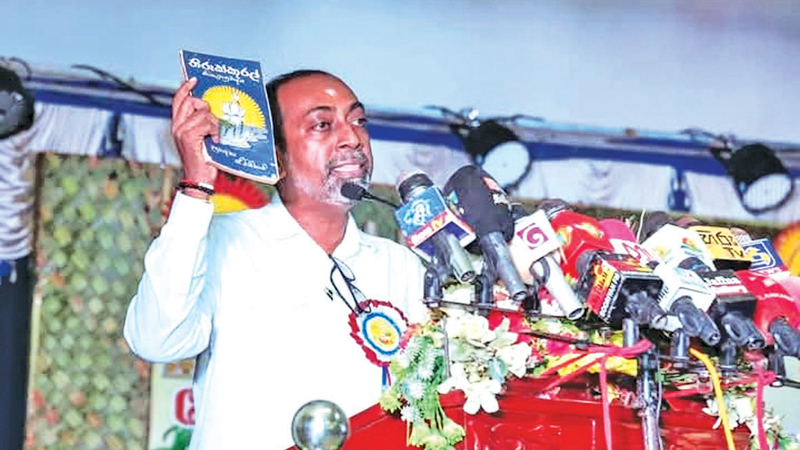

Cultural Affairs Minister Dr. Hiniduma Sunil Senevi, holding a copy of Misihami’s translation of Tirukkural in his hand said that it was an important cultural monument in our history.

G. Misihami is, perhaps, one of the first female translators of Sinhala, to appear in the modern literary scene. And she is the least known. When the Thiruvalluvar Cultural Centre was named as such, Minister Senevi said, ‘Misihami has translated the Tamil classic into an amazingly beautiful Sinhala.

A schoolteacher from Weligampitiya, Pokunuvita, published the Sinhala version of Tirukkural in 1961. In her preface, she acknowledges the help she received from S. Tambiah, a retired physician in Jaffna, who is equally unknown. Perhaps, the doctor might have worked at Pokunuvita, and they became friends. Such friendships between Tamil and Sinhala professionals were quite common those days. Even 30 years of war and the love loss resulting from it have not fully separated us from each other.

It is also unknown to what extent the doctor from Jaffna helped the translator in rendering the Tamil classic into Sinhala. Did he give her a rough translation and she polished it turning it into her skilled versification? Misihami’s short preface to the translation indicates that she had to struggle with some Tamil verses to get their word order right and to understand some philosophical concepts included in them. Perhaps that was where Dr. Tambiah stepped in.

Writing a short introduction to the book, late Professor Hemapala Vijayavardhane, then a young lecturer, stated that Misihami has spent some years translating the text. Hers was the first translation of the book into Sinhala, and no other translation happened even later.

Tiirukkural, however, has been influential in the classical literary culture. Sinhala classics such as Subhashitaya and Lokopakaraya are known to contain ideas and metaphors taken from Tirukkural. In other words, Tirukkural has been in circulation among classical Sinhala poets. Sinhala poets from the very early times were polyglots who had a commanding knowledge of several languages, and Tamil was among them. Though they wrote in a relatively small vernacular language, Sinhala, many classical poets had access to three trans-local languages Pali, Sanskrit, and Tamil. In modern terms, they were all international languages. Ven. Hisselle Dhammarathana Thera, in his book about the Tamil influence on Sinhala literature, has shown the extent of Sinhala and Tamil literary interactions.

I am no expert in Tamil classics, and I have read Kural in Sinhala and English. Even it is not in-depth reading. But having heard about the renaming of the cultural centre in Jaffna, I began reading Kural.

Kural, like many South Asian classics, provides insights into key aspects of happy human life. Written over 2,000 years ago, the book contains the acquired wisdom often found in nearly all religions in the Indian sub-continent. Some have found their way into Buddhism as well. ‘Virtue,’ ‘wealth,’ and ‘love’ are the main thematic lines under which the verses in Kural are arranged. All these three words, and their equivalents in South Asian languages, are extremely polysemic i.e. loaded with meaning.

‘Virtue’ encompasses everything related to ‘good’ life, and it is not just a religious term. Similarly, ‘wealth’ is not just material things, even happiness is a form of wealth. So is fame. ‘Love’ is both divine and human and spiritual and sexual. After all, sexual love contains within it a deep sense of spirituality, when sexual pleasure is realised within a domain where deep love rules. By and large, for me, Kural is a handbook of wisdom for household life. And those points of wisdom are expressed in often beautiful phrases and sentences. For that, I must praise Misihami, the translator. Such skills in crafting verses in elegant Sinhala, which has a flavour of classical poetic register that does not come naturally. It is sad that we do not know anything else written by her.

Virtues in Kural

Let’s look at some verses of Kural. Though I have an English translation of the text, I want to read Misihami’s Sinhala one paying respect to that historic poet. The section 10 of Kural is about ‘pleasing words.’ In verse 97, Thiruvalluvar says and Misihami translates,

‘If pleasing words that bring about good results are spoken, the law is kept, and it itself settles into virtuousness.’

Though this is significantly different from the English translation I have, the ideas expressed in the verse are not foreign to a Sinhala reader.

Section 10 of Kural celebrates the virtues of being ‘neutral.’ By extension, neutrality could mean ‘detachedness,’ – a term that generates Buddhist connotations.

‘Even if those who are neutral

end up becoming poor

Good people in the world

do not consider them weak(117).

Here too, the English translation differs significantly. But still Misihami’s Sinhala version makes perfect sense.

In the same section, ‘neutrality’ is articulated in the context of commerce:

‘Real profit of a business,

is the profit made by taking good care of

others’ property

as one’s own.’(120).

Perhaps, it is more meaningful today where nearly all businesses include others’ property in the form of ‘shares.’

From individual virtues of everyday life, the book moves into politics and statecraft about which South Asian classics always had something to say.

‘The king who is easy to meet,

Who does not hurt feelings of people

And does not speak harsh words

Are praised by world-dwellers (386)’

The chapter on this theme explains several qualities of a good ruler. Among them are ‘knowledge’, ‘courage’, and ‘perseverance’- the exact qualities we like to see in our government in a time of renaissance. And they are the virtues implied by the minister of cultural affairs when a cultural centre in Jaffna is named after the author of Kural.

Love in Kural

Tirukkural deals with several forms of love. Love in human life can take many forms. None is frowned upon in Kural. Friendship is also presented as a form of love. Misihami, the schoolteacher, does not shy away from translating beautifully crafted verses on sexual love. In either case, Kural promotes love that does not entail any utilitarian use. It is easy to love someone for the benefits it gives and for the many uses of that relationship. But love is really love when it is enjoyed for the sake of love or for the pleasure of being in love. So, the Kural helps us recognise many forms of fake love. In translating these sections, Misihami wonderfully utilises her deep understanding of poetic Sinhala and the skills in versification. At times, Thiruvalluvar’s metaphors are amusing. Here is the pain of a young woman in love separated from her lover:

‘My lover is within me day and night

So, I do not eat hot food

because I fear that

the food would burn him(1128).

Reading Kural in Misihami’s translation gives us many pleasures. Indeed, she deserves to have a cultural centre named after her.

Tamil Influence on Sinhala literature

Ven. Hisselle Dhammarathana Thera is another historic figure who widened our understanding of Sinhala-Tamil literary and cultural interactions. His 1963 book, Sinhalaye Dravida Balapema (Tamil Influence of Sinhalese Language) was, of course, published two years after Misihami’s translation. But from the 1950s, Ven. Dhammarathana Thera was writing to newspapers about what Sinhala literary culture had learnt from Tamil. And invited by Prof. E.R. Sarachchandra, Ven. Dhammarathana Thera gave a series of talks on the national radio on this theme. The first of those talks was broadcast in 1954. It is not clear how Misihami was inspired by those articles and talks by Ven. Dhammarathana Thera. He indeed discussed Kural and its influence on Sinhala literature.

We need significant changes in the structural makeup of our state making room for Tamil people to take part in the process of governing, especially at the upper structures of power.

Meanwhile, the understanding of our shared history must continue to grow. And it is a history that must be passed on to the next generations. I hope the Thiruvalluvar cultural centre in Jaffna, in its own way, will contribute to the growth of that awareness.