The classic Ceylonese vintage play, The Senator, written by H.C.N de Lanerolle was brought to life on the boards of the Wendt for a two day show run by Amphitheatre directed by Jaliya Wijewardene, who last year offered theatregoers in Colombo, Lanerolle’s Fifty-Fifty, which also revolves around the political advents of Dionysius Sumanasekera in pre-independence Ceylon. Seated under the gentle darkness, yours truly caught the show on opening night -March 18 settled in Q-7 as an observer, with observations for the Sunday Observer.

The first thing that caught my attention was that the curtain opened with some vintage melodic music to reveal the aristocratic household of the protagonist, setting a good tone and tune that gave character to the scene and the story’s era. I observe this aspect as a contrast to the performance of Fifty-Fifty directed by Wijewardene, last year. I did comment in my review in the 9th October 2016 issue of the Sunday Observer, how the opening music distinctive of that era could have improved the Fifty-Fifty production.

The use of music was a consistent audio element in The Senator when opening curtain for different scenes in the course of the play, and must be noted as a positive attribute of this production.

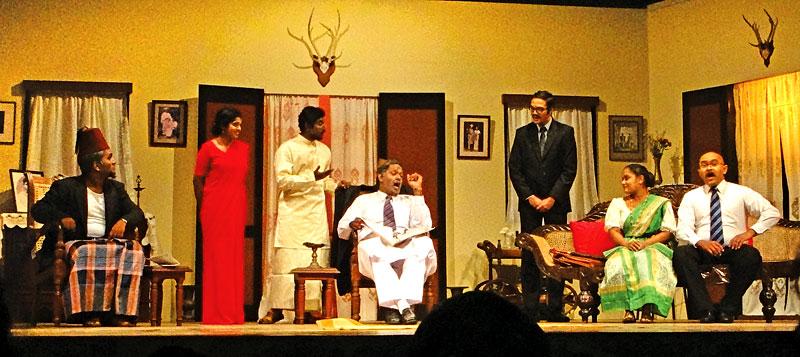

This Amphitheatre production can be applauded for good stagecraft and set design, as well as, wardrobe and makeup.

These commendable aspects resonated very much with the visual presentation of Fifty-Fifty and an affinity can thereby be observed between the productions.

On the acting front which is the flesh and bone of any theatre performance, I would say it was alright, with room for more oomph in certain places with regard to how dialogue could have been negotiated as interplay and not delivery alone.

I felt the overall performance could have benefitted through the use of dramatic pauses coupled with heightened facial expressions at certain points.

A good casting decision was visible with Yasal Ruhunage as Somapala the revolutionary, who commanded much of the spotlight through his innate skill as an actor. Jaliya Wijewardena did a fairly decent job in the lead role although he could have pronounced the character a bit more with facial expressions that add a touch of the dramatic to the persona.

Characterization of the protagonist included speaking English with substandard pronunciation, mixing up words that sound similar but carry different definitions, like ‘facilitations’ for ‘felicitations’, and also translating verbatim Sinhala idioms to English, one such example being, –“like tying ladders for jumping moneys.” These attributes from a point of dialogue and diction alone set Dionysius apart from the rest of the characters who are properly English conversant.

In this regard, one must note that the character of Hadjiar, played well by Sahan Wijewardene cannot be seen in the light of a character who converses in English, strictly speaking, since it is his role in the play that makes Lanerolle’s script a Ceylonese play that is technically multilingual and not solely English medium. Mrs. Sumanansekera played by Shenilka Perera was very well characterized and carried a healthy dose of theatricality.

The Sumanasekeras’ son-in-law Chelvam, was characterized as a mild mannered gentleman and convincingly played by Barana Waidyathilake. Kavinda Gunasekara must be commended for his compelling portrayal of the Englishman, William Buckham who was very much the ‘suddha’ (white man) straining to maintain facades of gentlemanly composure amid the rising (tropical) heat of political climates.

Jitters and blunders

The performance seemed free of opening night jitters until, Leyanvi Mirando playing Kamala Weerawardene fumbled with her lines in the last scene, when she says to the effect that she believes in thinking ahead for the future and not being besieged by the past. And it caught my observation that a few lines prior to the verbal stumble, she corrected herself without being conspicuous when she said to Somapala –“Your remedy is worse than the cure,” and immediately followed it up with –“Your cure is worse than the remedy.” I couldn’t make total sense of that line and assume what was intended was –“Your remedy is worse than the malady”? However be that as it may, except at the point of her gaffes with her lines, Mirando did perform her character well and can be appreciated despite the opening night mishap.

Curtain and lights

The time between the end of the first scene and the start of the second, inadvertently showed the audience players out of character running to their positions as the curtain parted before cue, and closed again. A ‘mistimed curtain’ between scenes happened more than once. The handling of the curtain on opening night was sinful.

Like the curtain, the lights too did a disservice to the performance at the end when the ousted senator declares his intentions for the future. The ending should not have been as abrupt as it was. The spotlight also switched off a bit suddenly, and disallowed the dramatic height of the moment to linger.

The perspectives for politics through theatre in The Senator, are manifold. When viewing theatre as a means of mass communication, Lanerolle seeks to artistically chronicle Ceylon at the door of independence. These Ceylonese vintage plays of Lanerolle form part of our country’s legacy in theatre. Like Fifty-Fifty, The Senator looks at how democracy of the wild ass will soon besiege our country as the 1940s beckoned the end of British colonial rule in the island. The party system and the manipulation of the country afterwards, by the former colonists through their lackeys, who although are said to be leaders of the people are practically proxies of the British, all come out through the course of this play, and especially, via the role of Buckam.

When Buckam is accidentally addressed as ‘Mr. Bunkum’ at one point, it was a nuanced statement of the light in which ‘British benevolence’ towards independence aspirant Ceylon could be viewed. Somapala’s character as the colonialism disdaining commie brings out some very striking critical insight as to how the guile of the British could be seen at the point they ‘amicably’ decided to accede to our country’s aspirations for independence.

Buckam’s show of ardent taste for local cuisine and culture sought to show a more ‘democratic’ benign colonist who appreciates the culture of the people they once oppressed. Expressing his disbelief about Buckam’s behaviour as pretence, Somapala seems to speak of how the people of this country should not fall for a new age myth as British modesty. After all, the vociferous revolutionary does say what was believable and distinguishable about the character of the British, was their arrogance.

The path to democracy

Lanerolle’s play doesn’t speak all too strongly for a clear need to end British rule but rather plays out through characters that possibly represented factions of that time, how the socio-political phenomenon of democracy and independence was viewed. In this, what can be said is that something of a theatrical treatise can be found in The Senator, on why democracy seems not an all too brilliant idea for the country at the time.

Let’s not forget that Sri Lanka received universal suffrage even before Britain, and we were in effect, as I do believe, an ‘experiment’ that served the empirical needs of the colonial rulers on how the popular vote works in societies such as ours.

The British at that point in time saw how suffrage movements were ripening in the west, and limiting the vote to chosen segments in society had to be faded out if the British monarchy and the capitalist establishment wanted to survive.

Electoral democracy in the hands of the wrong kind can quickly give way to ‘ochlocracy’ or ‘mob rule’. Was democracy, I dare ask, the weapon the British used on independence aspirant Ceylon? In these times, perhaps, Lanerolle’s play rings out profound truths that were foreseen at the most critical juncture of our country’s modern history. These are plays that must be examined for more than the comedy they offer to a people who have become increasingly ‘laugh addicted’.

Despite the setbacks on opening night, a budding theatre company like Amphitheatre must be appreciated for venturing to bring works of this genre to gain life on the stage for theatregoers to get a dose of Ceylonese vintage theatre classics.