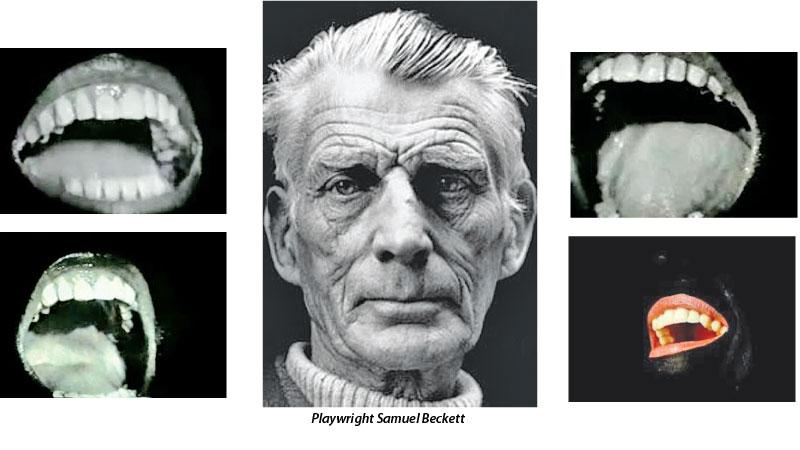

Sometime in the not distant past I was asked for my thoughts on a work of theatre by Samuel Beckett of which I had not previously known. The work is called Not I, a short dramatic monologue written by Beckett in 1972 and brought to life as a performance that same year. The request came from Lihan Mendis a young thespian whose acting talents I first encountered in Jerome de Silva’s production of Arthur Miller’s A View From the Bridge of which my review was published in the 13th November 2016 issue of the Sunday Observer. Lihan told me he is keen on exploring ‘the theatre of the absurd’ for which theatre practitioners like Beckett (along with playwrights such as Eugene Ionesco and Edward Albee) bear renown and have been instrumental in that theatre form distinction as a theatre movement.

Lihan emailed me the link to a video on YouTube that features a recording of a 1973 performance of Not I. the video can be watched on YouTube and has as its title – [1973] “Not I” (Samuel Beckett). After I watched the video and later and shared my thoughts with Lihan, I thought I could possibly expand my take on Beckett’s Not I for the readers of Sunday Observer. For what it’s worth this piece may offer some food for thought to those interested in theatre as an art that becomes a medium of communication. And for the record this article is not a theatre review of Not I. I have not watched a performance but only a video recording of a performance. It is my belief that no theatre reviewer should try to pass off a review of a video of a stage play as a ‘theatre review’. The essence of theatre after all is for an audience to experience ‘live acting’ and not a recording of it.

Not I is a monologue that is performed by a mouth. The actor’s mouth is the only visible sight. A mouth juts out from a hole of a black cloth like vertical surface and speaks dramatically with expressions varying in tone and pace. Firstly I felt the play seems to really put to the test (and successfully at that I believe) Einstein’s theory of time’s relativity.

The approximate 12 minute duration of the performance felt much longer when I watched the video. I felt like more than half an hour must have lapsed. It feels tedious to sit through it, I will confess. In that sense I suppose one could say Beckett’s Not I is like an application of a facet of the theory of relativity.

Not I when listened to is subjectivity to the extreme. The lack of a concrete ‘premise’ or background by this monologue (within its own text as words) distances the viewer/s from the usual common ground of understanding of what brings the performance and the viewer together as a scenario that is mutually understood for its background and premise.

In a way it’s a highly introverted scenario that disregards the need to apprise any other the ongoing thoughts inside the speaker’s head. It’s very much a slice of a psyche at a given moment of time, sort of thing.

It’s powerful. And by that I don’t necessarily mean in a positive way. Power can be either way. Not I seems powerful in the way it can seem disturbing, unnerving, and can rattle a viewer’s complacency with very little resources being utilised for the execution of the plan and design. It’s just a mouth lit up in the pitch dark. Just watching the video made me think sitting through an actual live performance would/could be rather daunting. It can seem jarring for that matter.

One of the contentions I would have with this approach by Beckett is - how effective is Not I as a means of successful communication if going by the ‘sender - message - receiver’ doctrine in communication theory/studies.

Theatre in one sense is about communication. And what is interesting to note is how what is called ‘noise’ in communication theory, elements that garble or obstruct the message’s clarity when conveyed to the receiver, ‘act’ in this performance. ‘Noise’ can be either external or internal factors. External factors can be physical elements like the environment that surrounds us, and internal factors can be psychological reasons.

The sheer overpowering weight of the monologue that is Not I seems to create its own ‘internal noise’ and falter in efficiency to clearly convey the total message. There is to my understanding a facet of ‘psychological noise’ within the monologue which conveys the impression that this speaker is clearly ‘disturbed’ and the message is therefore delivered containing/reflecting the anxiety, tension, fear and such negative psychological issues that are contained in the psyche of the speaker.

But the question I felt that must be asked is does the text of Not I have embedded in it ‘psychological noise’ that intentionally disrupts the message for the receiver, or is it because the performance with its tone and pace creates a highly negative emotional stir in the receiver to make the ‘noise’ occur within the receiver (audience)?

Not I in that respect is very self indulgent and seems to be happy with its platform of self indulgence presenting the form of an unbridled outpour. This kind of work shows the paramount need felt by a playwright to assert individuality and shows scant regard for anyone other than the self. By this I’m not by any means trying to draw a line of moral judgment at all.

The need for the self to present individuality and existence as an individual, seem to be the basis for this kind of work. This is in a way existential(ist) theatre! At least it seems to be as far as I can see when read in conjunction with what I learnt as an undergrad in Colombo varsity about ‘the theatre of the absurd’ and the events that marked its rise.

The literary technique ‘stream of consciousness’ which is called ‘the internal monologue’ in literature was pioneered by writers such as Virginia Woolf (her novel Mrs. Dalloway being a prime example) and James Joyce (his novel Ulysses contains examples of this technique). One of the central objectives of ‘stream of consciousness’ is to present the psychology of a character with the natural discursiveness and cursoriness that occur in human thought, as an ‘unfiltered’ narrative.

Beckett’s monologue delivered from a mouth would make Virginia Wolf blush, or perhaps proud? Stream of consciousness is by no means easy to achieve.

And I feel the literary technique of stream of consciousness gains a loud living form on stage through Not I, and is therefore demonstrative of how art in Europe evolves through interconnection between the arts.