PANAMA: It has been a long wait for five villages in Panama, Ampara. With over 1,220 acres of their land occupied by the Sri Lanka Navy and Air Force, the villagers have been fighting a long drawn battle since 2010 to reclaim the land they once lived and farmed on.

The people of Panama were overjoyed when a Cabinet decision in February 2015 ordered the release of land occupied by the forces in Panama back to the original inhabitants of the area. The Cabinet Paper ordered the release of 340 out of 365 acres of land seized in Panama, with the Government promising to pay compensation for 25 acres being occupied, since buildings had already been constructed in that area.

However, despite this decision there has been virtually no follow through by the authorities, and with major tourism plans for Panama in place, the fight for land in the pristine, verdant region continues, eight years since residents were driven out from their homes.

According to the People’s Alliance for Rights to Land (PARL), a voluntary coalition of civil society organizations and individuals working against land grabbing, 350 families of farmers and fisherfolk living in Panama, a small coastal village located at the very edge of the Eastern Province, were forcibly evicted in 2010 from lands they had lived on for more than 40 years. PARL which works closely with the displaced communities in Panama, says, the lands were initially taken over by the military to establish camps, but were still being used to promote tourism.

According to the People’s Alliance for Rights to Land (PARL), a voluntary coalition of civil society organizations and individuals working against land grabbing, 350 families of farmers and fisherfolk living in Panama, a small coastal village located at the very edge of the Eastern Province, were forcibly evicted in 2010 from lands they had lived on for more than 40 years. PARL which works closely with the displaced communities in Panama, says, the lands were initially taken over by the military to establish camps, but were still being used to promote tourism.

The land belonging to the family of W.M Asoka Dayani is now cordoned off and lies within the Navy camp in Panama. “Our land was just beyond the current entrance to the camp” she says.

She and 20 other families had lived in Ulpassa, which was now inside the camp. Despite holding a legal land permit, Dayani is now barred from entering her property by armed soldiers and barbed wire fencing.

A recent Right to Information application filed by residents has proved that land occupied by the military had never been legally transferred to the forces by the authorities.

Approvals have never been obtained to construct the camp from the Central Environmental Authority or Coast Conservation, residents learned through their RTI application.

Despite this, the removal of camps appear impossible with the authorities clearly looking at alternative land to provide to the people, a fact that upsets Dayani.

“That is the best agricultural land in the area and it belongs to the people of Panama” she says.

Despite some villagers from Shasthrawela being called for a meeting recently at the Ampara District Secretariat to discuss their land matter, those of Ulpassa, Horowkanda, Egodayaya and Ragamwela claim they have not heard from the authorities in recent times.

“They do not even mention our land which is within the Naval camp” Dayani laments.

The sudden interest to provide land to 15 permit holders in Shasthrawela, the villagers suspect, is to remove any dissent against a proposed government housing scheme in the area.

“Those who get homes have been asked to promote tourism and build homes according to the regulations” Dayani says adding that tourism seems the focus of the authorities, rather than providing houses to the people.

Unlike those in Ulpassa, the villagers of Ragamwela have not been patient. Instead, two years ago they entered the area forcefully going on to build homes and farm on the land they once used to live in, which is now within the Air Force base in Panama.

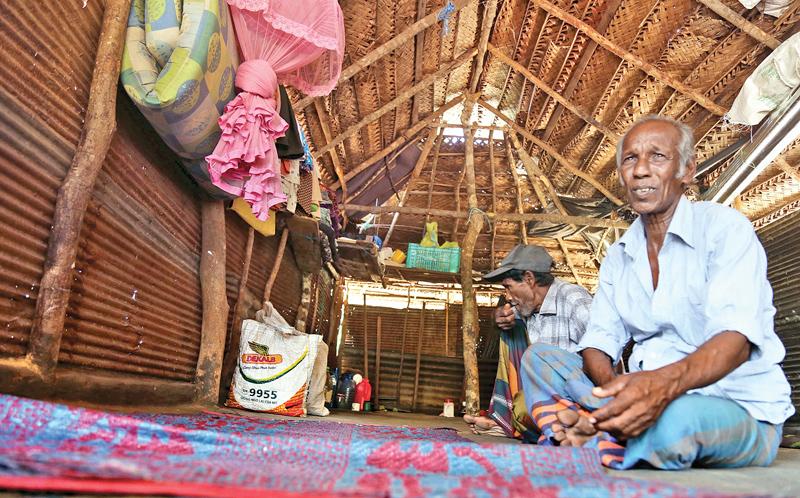

Aging Gunawardena Heennilame was one such resident who decided to forcefully enter the area. “I will not leave now even if they kill me” he says adding that, he along with his wife lives in constant fear. “We fear the soldiers, the authorities and the wild elephants” he says. According to him despite the suffering, he is unwilling to leave his home and encourages others also to take back their land.

Since being driven away from his home in 2010 by unidentified masked men believed to be backed by the then government, this is the first time since 1970 that he has been able to live in his land without interruption, he says. “I still remember that night” he recalls.

“They burned down our houses, fired at us and drove us away” he says. Though eight years have lapsed no culprits were ever caught. Despite the fearful past, Heennilame is now determined to remain in his land.

But it is a life of suffering. According to Heennilame water and land scarcity makes it difficult to grow crops while the presence of the Navy has disrupted fishing in the area. “We have no livelihood as a result” he says.

According to the main organizer of the People’s Movement to Protect Panampattu, P. Somasiri, who is also a fisherman in the area, the lights from the Navy jetties disrupt fishing in the lagoon while the Navy has also restricted certain activities, blocking access to other areas where the villagers once used to fish. “The fisheries industry in Panama is suffering” Somasiri claims.

Heennilame feels he has been tricked. “If a government decides to implement a plan then what is this delay?”

Heennilame feels he has been tricked. “If a government decides to implement a plan then what is this delay?”

While the land issue is also locked in several legal battles between the people and the authorities, the Divisional Secretary of Lahugala, Sandaruwan Anuradha says, complications exist in distributing and allocating land to the people and this has led to delays in implementing the land release.

“Even when the Cabinet decision was announced, the previous Divisional Secretary tried to divide the land, but it proved difficult” he says.

Some people had lost their permits, and others had not renewed them for many years, making land allocation tough. According to him, however a plan has now been proposed to give alternative land to all who have a claim.

“We have allocated 150 acres for the purpose” the Divisional Secretary says. But, the people must understand that the allocation of the same amount of land they once had is not possible now, he says.

While most land seized by the military in the war affected Provinces of the North and East happened while the conflict was raging, the Panama land grab, as activists call it, happened after the war ended in 2009.

But, the Sri Lanka Navy claims the Naval base is much needed for the country’s security. According to one naval officer, the base in Panama is the only one in the country’s coast between Trincomalee and Hambantota.

“There is a lot of smuggling in the area, by sea” he said adding that the Navy actively works to curb these issues.

But, since setting up the camp the Navy has even built a hotel on lands belonging to the people of Shasthrawela. The mere mention of Malima Lagoon Cabanas operated by the Navy irk the residents in Panama.

“There was no interest in these lands or its people during the war, but now everyone wants a share of it” Dayani says adding that the villagers are not in need of any extra security, which they did not have even during the times of war.

The residents of Panama have never been proponents of mass tourism. Located beside the tourism hub that is Arugam Bay, the Panama communities hold strong views about how tourism could ruin their pristine environment. To date, Panama is sheltered by thick mangrove forests and sand-dunes, which had proved a life-saving natural barrier when the tsunami happened in 2004. Neighbouring Arugam Bay was decimated, but Panama survived almost unscathed.

With its lush paddy-fields and thick wooded areas, butterflies, birdsong and the odd meandering crocodile, Panama was God’s own country, villagers used to say.

The land rights battle still raging in the region is also about keeping it that way.