Three rocks arranged in a circle. Firewood inserted in between. The cooking utensil is placed on top of the three rocks and the firewood is lit. As the flames die down, blowing into the hearth reignites the flames. Welcome to cooking with the firewood hearth.

Cooking with firewood is popular in many rural areas, estates and low income families in Sri Lanka. Commonly called the dara lipa in Sinhala and verehi adappu in Tamil, it used to be a common fixture even in city homes until a couple of decades back.

Cooking with firewood is popular in many rural areas, estates and low income families in Sri Lanka. Commonly called the dara lipa in Sinhala and verehi adappu in Tamil, it used to be a common fixture even in city homes until a couple of decades back.

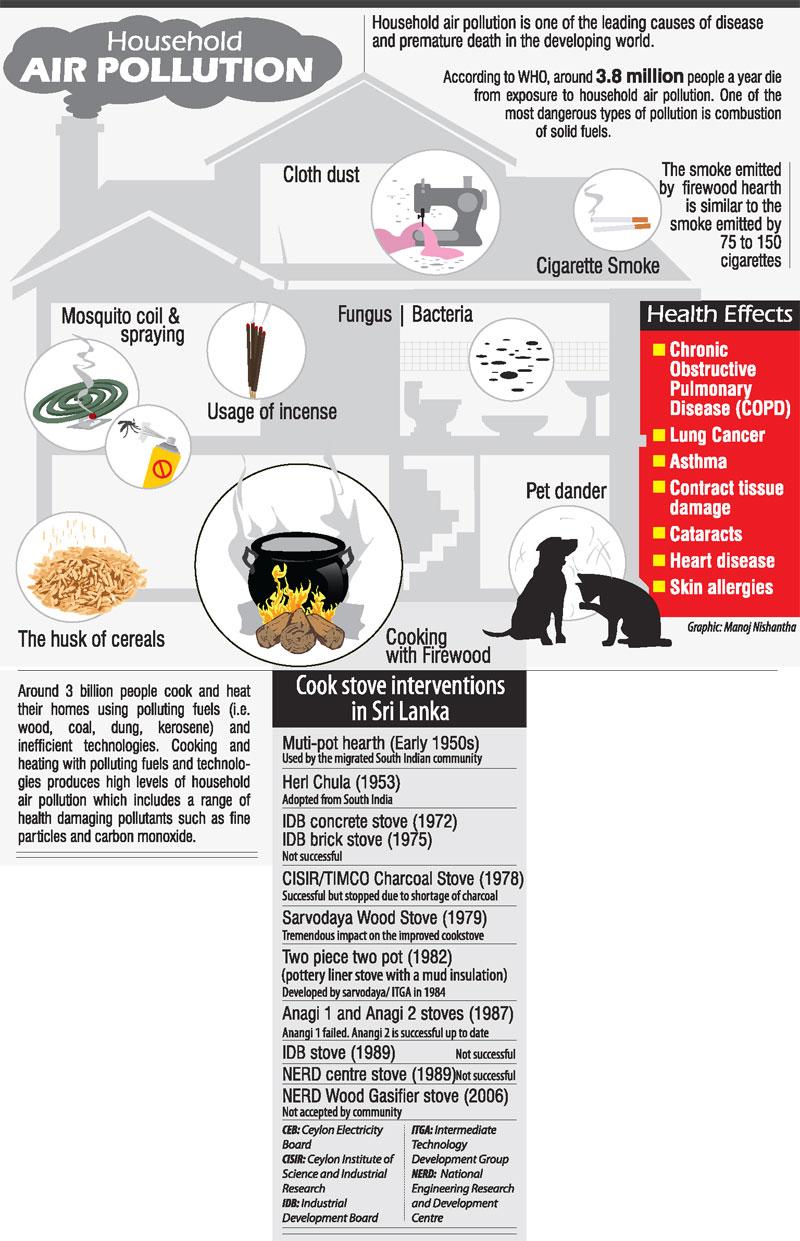

Around the world more than three billion people – nearly half the world’s population - cook and heat their homes using fuel like wood and charcoal on open fires or traditional stoves. This inefficient method produces lots of smoke creating Indoor Air Pollution (IAP). The World Health Organisation (WHO) says IAP kills more than four million people every year.

IAP from combustion of solid fuels for cooking and space heating is one of the ten most important risk factors contributing to the global burden of disease. It is estimated to account for over 1.5 million premature deaths and 38.5 million Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs). The WHO estimated that the number of deaths attributable to IAP in Sri Lanka recently was 4,300.

The Sunday Observer spoke to two housewives from different communities and areas using firewood for cooking. This is what they had to say. “I am used to cooking with firewood and my family likes the taste of the food too. I live in a rural area in the Kandy district and there is plenty of firewood for us. We cannot afford to cook by LP gas as our monthly income is low. I am somewhat aware that wood stove cooking is dangerous but we still cook,” says 50 year old Kusuma Wimalasooriya.

Fathima Nazreen from Colombo says that she always cooks using the LP gas but still occasionally uses the wood stove for cooking curries such as polos, jakfruit, beef and pickles as it makes these foods tastier. “Though we are aware of the risks of using the hearth and can afford the LP gas, we still use it for the taste,” she says.

Pulmonologist Dr. Dushantha Medagedara from the Kandy General Hospital says that the risks of IAP are not second to smoking. “The smoke emitted by the firewood hearth is similar to the smoke emitted by 75 to 150 cigarettes. The risks of cooking with firewood are much higher than smoking two cigarette packets daily. Mothers, housewives and small children who are at home most of the time are the biggest victims of this pollution. This situation is not only found in Sri Lanka but also in South Asia, Africa and South America,” he said.

“In the past our kitchen was outside the house but now due to the lack of space, the kitchen is inside. We use plastic, polythene, kerosene and wood in the firewood hearth so the smoke emitted by the fireplace leaves particles that are harmful to the body such as carbon monoxide, nitrous oxide, and sulfur dioxide. The poisonous gas circulates throughout the night inside the house due to the lack of ventilation and the improper way of transmitting the smoke out,” he explained.

“The health problems caused by cooking with firewood are numerous and women are more vulnerable. They develop chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), lung cancer, asthma and contract tissue damage. In order to control indoor household pollution to a certain level, I recommend placing the hearth outside the house. If there is a hearth inside the house, using large windows in the kitchen can control the situation up to a certain level,” he added.

According to 16 epidemiological studies identified by a scientific review in 2010 and several preliminary data from ongoing studies by Dr. Sumal Nandasena, Specialist in Public Health and Community Medicine, National Institute of Health Sciences, it is estimated that indoor air pollution resulting from exposure to solid fuel accounts for over 1.5 million premature deaths and 38.5 million Disability-Adjusted Life Years in Sri Lanka.

Dr. Nandasena says that biomass fuel is the main source for cooking for the majority of Sri Lankan households, and the heavy use of wood-burning stoves in Sri Lanka is the leading contributor to IAP. “High concentrations of indoor air pollutants represent a significant health issue for Sri Lanka; comparative research in other countries has confirmed that IAP from solid fuel use is a major cause of premature deaths as well as acute and chronic diseases. This issue, however, is not broadly researched or prominent in Sri Lanka public health policies and programs. There should be further analytical study to inform new public health policy, advocacy and programme interventions,” he said.

“As in many countries, biomass stove use in Sri Lanka is most common in rural areas and estates. Over 78% of households nationwide burn wood in biomass stoves; 84% of these households are in rural areas, and 96% are households on rural estates. Even in urban areas, over 34% of the population uses wood as their main fuel source. Although more than 80% of the Sri Lankan households have electricity, it is used primarily for lighting, and wood is used for cooking,” he said.

According to Dr. Nandasena’s research, biomass stove use is most prevalent among rural and poor populations, and both of these conditions present significant barriers to the use of more efficient, safer stoves and cleaner fuels.

The rural poor are the least likely to use cleaner fuels or a ventilated kitchen because the costs are prohibitive.

Experience from other countries shows that biomass stove research and community-based initiatives that have targeted the introduction of new and improved stoves often failed to adequately account for lifestyle and cultural practices in research and programme design. Despite Sri Lanka’s well-established public health system and relatively good public health indicators, IAP issues have been poorly studied to date. Synthesising the available information on biomass stove use is an important essential first step to identify gaps, impact, and feasible interventions to address the biomass cook stoves in Sri Lanka.

“Biomass use in Sri Lanka is limited to wood. Crop residues may be served as alternative cooking fuel sources where wood is not readily available.

Although over 80% of Sri Lankan households have electricity, this energy source is used for lighting because it is too expensive to use for cooking. Even in urban sectors, where electricity, LPG and kerosene are more likely to be used for cooking, their use is largely confined to boiling water,” he added.

According to his research within Sri Lankan homes, the majority of wood stoves are either three stones or semi-enclosed stove types. The ‘Anagi’ is an improved cook stove made of clay that has been available since the 1990s and is still used today.

A national estimate of cook stove types across the entire population is unavailable. Emissions from the improved cook stoves in Sri Lanka are not available with scientifically rigorous methodologies.

Approximately 65% of the households using biomass fuel cook inside their main household structure, while only 9% have a separate building for cooking.

About 72% of the households using biomass cooking stoves have a chimney in their house/kitchen. These stoves’ thermal efficiency is very poor, and there are significant quantities of emissions released into poorly vented indoor settings.

Traditional biomass fuel stoves produce particulates, carbon monoxide, nitrous oxide, sulfur oxides, formaldehyde and polycyclic organic matter, which includes carcinogens such as benzopyrene. Particulates are harmful because they penetrate deep into the lungs. These particulates cause bronchial irritation, inflammation and fibrosis and can lead to wheezing, exacerbation of asthma, respiratory infections and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Carbon monoxide prevents haemoglobin from delivering oxygen to key organs and the developing fetus. Nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide increase bronchial reactivity and lead to wheezing, asthma and more serious respiratory problems like lung infections and COPD. Biomass smoke also causes oxidative changes to the eye’s lens and leads to cataracts.

A number of national agencies are involved in aspects of air pollution regulation and monitoring in Sri Lanka.

The development of policies and programming focused on IAP is largely centralised at national level. Cities and local governments have shown limited interest or have not developed expertise in this area.

The Ministry of Environment (ME) and Natural Resources (NR) have lead responsibility for environmental management in the country. Within ME and NR, the Air Resources Management Center (AirMAC) is established to provide leadership for policy and regulatory issues related to air pollution monitoring and control. Several non-profit and community organisations are active in Sri Lanka on issues of IAP and improved cook stove development.

The Integrated Development Association (IDEA), based in Kandy, Sri Lanka, is an NGO focused on promoting sustainable development and natural resource management. One of IDEA’s programs was the development, testing and promotion of the ‘Anagi’ (precious or excellent in Sinhala) indoor cook stove, which is a two-pot, one-piece clay cookstove.

“Shifting from biomass to clean fuels is challenging in reality. With a new focus on IAP, Sri Lanka is well equipped to tap its strong public health system and government infrastructure to address IAP from biomass fuel use.

A combination of technology, education and outreach that is culturally appropriate, affordable and convenient will be critical factors for successful programming. New global initiatives, such as the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves (GACC), provide valuable advocacy, and may potentially provide financial resources, to advance understanding of environmental risks and pursue new programming to reduce the risks from IAP,” says Dr. Nandasena.

The urgent need to tackle the deadly effects of household air pollution was not even on the agenda of the international community until two years ago.

Left out of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) adopted by the United Nations in 2000, the world opened its eyes to the dangers of IAP in 2015 when world leaders put their stamp on the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be achieved by 2030. Goal No. 7 was Affordable and Clean Energy.

In India, the government provided 80 million LP Gas stoves under a scheme to the poor in order to achieve the MDGs. The Sri Lankan government also needs to address this problem and find solutions to achieve a clean cooking target and minimise IAP.