As a disabled writer, I will use both person-first and identity-first language interchangeably for purposes of brevity and clarity.

It’s easy to confuse the history of disability portrayals in TV sitcoms with the ‘very special episode’ that specialised in dark topics followed by comforting homilies, all sound tracked by awkward laughter from the live studio audience. However, if you look back at the episodes that featured characters with disabilities, they weren’t the stuff of VSEs. They belonged to narratives about the disability, all with a single mantra: People with disabilities are simply people.

An innocuous, if obvious, lesson, but here’s where the VSE confusion might arise: These sitcoms didn’t feature full-fledged disabled characters. They tended to be two-dimensional cardboard cutouts that were not meant to have lives of their own, but rather teach the able bodied how to be better people.

This wasn’t always the case. In the 1967-1975 crime series Ironside, Raymond Burr’s paralysed detective often navigated accessibility issues. In fact, Ironside was the first television show to present a wheelchair-accessible van. It looked like a paddy wagon but, hey, it’s a start.

As Dr. Loveless in The Wild, Wild West (1965-1969), Michael Dunn became one of the first little people to regularly star on television; Herve Villechaize became famous on Fantasy Island (1977-1983). They participated in dramas that didn’t stem from their characters’ disabilities or limitations; the actor simply was. (These portrayals had issues of their own, but that’s a story for another article.)

The VSE glory days arrived with All in the Family, where Edith pushed a still-hot cake into the face of a would-be rapist that she allowed into their home (Edith’s 50th Birthday). The TV equivalent of eating your vegetables blanketed with yummy cheese sauce, they allowed viewers to absorb discomfiting information and still end the episode with a sense of optimism and hope.

By contrast, episodes that included disabled characters weren’t prefaced by a cast member breaking the fourth wall to alert (or warn) audiences of the content they were about to see. Nor did the episodes communicate a sense of fear, uncertainty, or death. However, unlike Ironside they failed to treat disability as simply a facet of a person. It was something to tackle — an opportunity to educate, illustrate an object lesson, or create a special event. For this reason, disability portrayals in sitcoms were the stuff of bottle episodes; even if the actor was a recurring guest star, they never had the opportunity to simply be a member of the cast.

In a 1977 episode of Lear’s Good Times (Breaker, Breaker), young Michael (Ralph Carter) experiences the ’70s equivalent of a chat room: the CB radio. He starts talking to a young lady with the handle Fun Girl (Sharon Brown) who, the audience learns, is in a wheelchair. Brown is an able-bodied actress, but to the show’s credit the character was a Black disabled teen — a rare representation, and one of the only Black characters with a disability in television at the time.

That said: Breaker, Breaker is all about what Michael learns through Fun Girl. Over the CB, she and Michael talk about all the fun activities they can do that involve walking, and when Michael goes to her apartment he discovers … she can’t walk at all! This is presented to the audience as a betrayal by Fun Girl, and a moment of confusion for Michael; after pretending to have entered the wrong apartment, he runs away.

Later, Fun Girl goes to Michael’s house to apologise and discovers he was the boy who visited her apartment. She says the CB allows her to be anyone she wants — and since the audience knows only her disability, this implies that her life is sad and lonely. Michael says they can do other activities (because dancing and taking walks are apparently not wheelchair friendly), and in the end Michael’s brother J.J. (Jimmie Walker) praises him as a “beautiful soul.” We never learn anything about Fun Girl beyond her real name (Nancy Colton) and her use of a wheelchair, and she is never heard from again. The lesson: Disabled characters help able-bodied people learn about empathy. (Lear did not return a call seeking comment.)

Similarly, in the 1990 Golden Girls episode Stand By Your Man, Blanche (Rue McClanahan) goes on a date with a man in a wheelchair (Hugh Farrington). Much of the story involves Blanche overcoming her preconceived notions about people in wheelchairs, only to discover that the man is married. Here, the lesson is disabled people are just like everyone else: They can be cads, too! (Disabled characters as heartbreakers was a refreshing change of pace.)

In a 1980 episode of (Allison), Linda Bove (later the first deaf series regular on Sesame Street) is a deaf woman working at the electric company. She attracts the Fonz (Henry Winkler), who goes on a journey to learn sign language to woo her. Like Breaker, Breaker, we don’t know anything about Allison outside her disability, but Fonzie’s commitment to learn how to sign, rather than convincing her to speak, is unique. Even more interesting: Allison reveals that she’s not in love with him, but is going to marry another able-bodied man who learned sign language for her. This allows Allison to be a one-and-done character, but at least it steers clear of “shipping” — pairing disabled characters strictly because they are disabled.

The 1992 Saved By the Bell episode Teen Line may have been the first TV show to utilise a disabled character to illustrate the perils of ableism. It centers on clueless high school stud Zack Morris (Mark-Paul Gosselaar), who goes on a blind date with Melissa (Jennifer Blanc-Biehn) and learns that she uses a wheelchair. (Interestingly, she’s one of the few TV characters at this time who is disabled from birth.)

“He really had the wrong reactions to every possible situation,” Blanc-Biehn told IndieWire. She said she worried at the time about taking the role as an able-bodied actor, and later was struck by the long-term backlash the Zack character received for treating Melissa so horribly.

Zack likes Melissa, but takes it upon himself to cause a scene while taking her to a movie, and creates a charity basketball game that has able-bodied Bayside High School kids playing in wheelchairs. She tells him off, but by the end of the episode she lets him take her to a dance. The episode is meant to show audiences that Melissa is just an average girl — but since there are no other disabled characters in the series, Zach’s educational experience is trite.

Several Diff’rent Strokes episodes focused on disability, the most famous of which are four between 1981-1984 that starred Melanie Watson as Kathy Gordon. She’s introduced in Count Your Blessings when Arnold (Gary Coleman) is upset because he’s learned he will not grow taller than five feet. Although Coleman had congenital kidney disease, that’s not mentioned in Arnold’s story; the revelation isn’t couched as a disability but as a fact of life.

To make Arnold feel better (and, dare we say, count his blessings), his adoptive father Philip (Conrad Bain) calls in a friend whose daughter is disabled. Kathy, who has brittle bone disorder and uses a wheelchair, arrives with the goal of not only being Arnold’s friend, but also helping him realise his life could be worse. She tells him that she’d be totally happy to be a Black boy who could run. That’s a cringe-inducing line, implying that she’d be willing to “downgrade” to being a Black child if it meant she was able-bodied. Her own white privilege goes unexamined.

Just as Kathy galvanised Arnold into doing things he didn’t want to do, he challenged her — but to weird effect. In Kathy (1982), Arnold is coerced by Philip and Kathy’s mother to convince her to start walking with her crutches. Never mind that Kathy doesn’t want to do it; her mother and Philip believe it’s best for her. So, Arnold and Kathy have a fight that leads to a third-act conclusion where, in order to get Arnold to go on stage, Kathy arrives on crutches and convinces Arnold to go on with the show. Beyond the disturbing Tiny Tim imagery of a girl being forced to walk for the benefit of able-bodied people, the decision isn’t hers.

Kathy did mark a happy new trend in disability portrayals: Watson was a disabled actor. (She did not respond to an interview request.) While disabled actors made appearances on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and Sesame Street, recurring guest stars with disabilities was new territory. That continued with Geri Jewell on The Facts of Life, who appeared in 12 episodes between 1981-1984. Series creator Norman Lear wrote the role of Geri Tyler for Jewell, who has cerebral palsy. “They had never seen anything like me before, so I broke through that wall just by being me,” Jewell said.

Geri is introduced as the cousin to the snooty Blair (Lisa Whelchel) and the difference is striking. Where Blair is beautiful, composed, and privileged, Geri is loud and brash. There’s a privilege barrier, but there’s also nuance. Blair doesn’t pity Geri for being disabled; she feels bad about herself, since she feels like she hasn’t accomplished anything as an able-bodied person (a conclusion that comes with its own host of questions). Geri is self deprecating in her introduction — a common icebreaker for disabled characters — but never presents as dependent. The other girls at the Eastland School for Young Women are surprised to learn that she can drive! And she’s a well-known standup comic! In her third appearance,Cousin Geri Returns (1981), we see Geri dating a good-looking, able-bodied man — and maybe she isn’t a virgin? With most disabled women presented as asexual, that was a TV breakthrough.

Unfortunately, the Geri character never becomes integrated with the cast. Jewell said she often felt like Geri Tyler had to represent for every disability; the writers trotted her out as a sounding board for able-bodied characters, as when Tootie (Kim Fields) faced hearing loss. Ironically, Jewell also had hearing loss and wore hearing aids, but didn’t tell anyone on set for fear it would be too much for the producers to handle. “In my mind I thought, ‘Okay, they just embraced and accepted [the] cerebral palsy,’” she said.

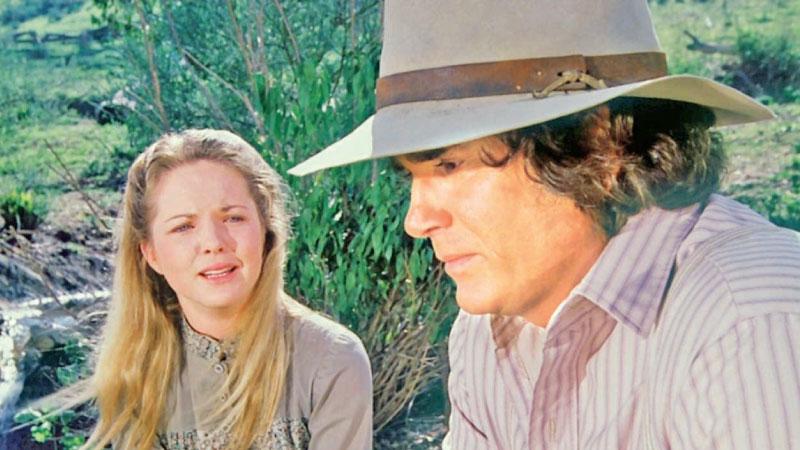

Other shows preferred to heap tragedy on disabled characters. On Little House on the Prairie, Mary Ingalls (Melissa Sue Anderson) became the series’ inspiration-porn star after the 1978 two-part episode I’ll Be Waving As You Drive Away, in which Mary becomes permanently blind.

The show represents Mary’s blindness as a gradual progression that forces her to face fear and hostility. Anderson did her homework, attending the Foundation for the Junior Blind and learning to read Braille, but the story problems began once the show resolved Mary’s initial struggles with being blind.

Anderson told Indie Wire that she knew her character, like the real-life Mary, would become blind and feared that meant she’d be written out of the series. Instead, she became the focus of episodes that capitalized on Mary’s suffering.

Mary is sent to a school for the blind, gets married, and bears a child — and then she’s in a wagon accident, and loses her baby in a horrific fire at the school. When Mary was left standing in crowd shots, having things explained to her by her loving Pa (Michael Landon), Anderson decided to leave the series entirely.

“There was only so much they could have me do once I had every tragedy known to implement,” she said.

Word: Kristen Lopez