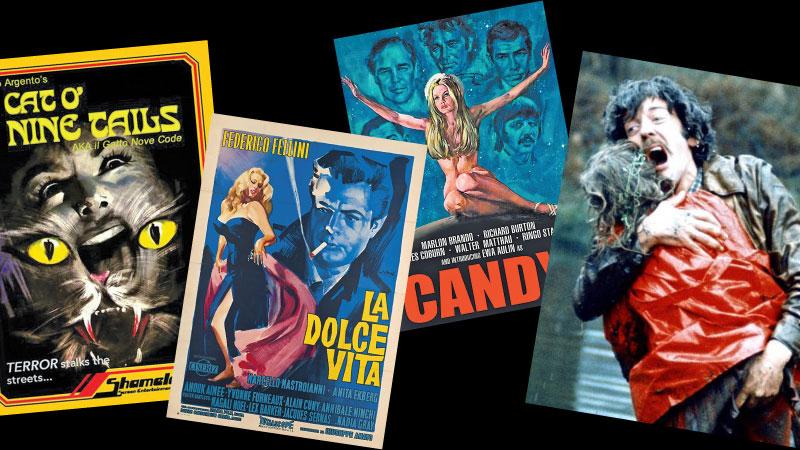

Candy (1968)

Ewa Aulin, the star of Deadly Sweet and Death Laid an Egg, plays the eponymous Candy; a naive, somewhat gormless, sexually accommodating teenager who, through a series of bonkers episodes, manages to appear unrelentingly catatonic. Even while she disrobes for Beatles drummer Ringo Starr in his frankly embarrassing turn as a South American seminarian gardener.

A star studded supporting cast, featuring the likes of Richard Burton, Enrico Maria Salerno and Marlon Brando, attempt to lend gravitas to this visually striking yet overly long, pretentious, Rohypnol soaked, hippy sex farce nonsense. They do not succeed.

La Dolce Vita (1960)

La Dolce Vita (1960)

La Dolce Vita is an episodic study of a thrill-seeking gossip columnist who spends his time among bourgeois bohemians as they party in the glare of the flashbulb. Yet, as with the characters from Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Aventura, from the same year, these are people who are clearly searching for..... something. So we are treated to a voyage within the realm of poverty tourism, a communion with the supernatural, the quest for miracles, a frivolous splosh in the Trevi Fountain and immersion in the intoxicating exoticism of Orientalism. However, despite trying, these socialites never seem to really connect.

Their emptiness is one that viewers are allowed to share as diegetic scoring leaves plenty of aural whitespace. Although this, in turn, is punctuated with much inane chatter and a lot of glitterati bellyaching over what could best be described as first world problems.

Adopting a similar approach to Juliet of the Spirits, director Federico Fellini allows things to simmer somewhat, but ultimately pulls the various strands together with an exhilarating crescendo of absurdity. Marcello Mastroianni stars.

Cat o’Nine Tails (1971)

The Cat o’Nine Tails is Dario Argento’s surprisingly artless followup to his stylish blockbuster giallo, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage. The elements that made the first film of his ‘animal trilogy’ a much imitated classic — Hitchcockian plot twists, Vittorio Storaro’s Pop-fabulous photography, deviously innovative murders—have gone missing in this standard-issue murder mystery.

A series of crimes committed at a genetics firm brings together blasé reporter James Franciscus and sympathetic codger Karl Malden, who traded journalism for crosswords, with the help of his orphaned niece, after an accident left him blinded.

The misleadingly kinky title refers to the number of clues on the trail to discovering a serial killer, as well as his weapon of choice, a whiplike wire for garroting.

There is a welcome stab at humour, as when Gigi ‘the loser’ is enlisted in the manhunt, and the frenetic jazz score is prime Morricone. But the story is flat, the lighting is flatter — a crypt as bright as a supermarket by a single flashlight—and blood has the unconvincing hue of fruit punch.

But there’s no shame in shunning Argento’s career-low clinker: the director described it as his least favourite.

Don’t Look Now (1973)

Don’t Look Now (1973)

The middling menace-in-Venice horror film Don’t Look Now, based on a Daphne du Maurier novella, is low on chills but high on arty, foreboding atmosphere. The latter quality is to be expected of celebrated cameraman-turned-auteur Nicolas Roeg. Church restoration expert Donald Sutherland is in the city to work on an old basilica, with wife Julie Christie in tow. The two are racked with grief and guilt following the accidental drowning of their little daughter. Except for one lovemaking scene, fragmented by showy slice-and-dice editing left over from the psychedelic era, the two are alienated from each other. One suspects that pages of their aimless dialogue could be ripped from the script and the story wouldn’t suffer.

Roeg’s Venice is remarkably free of tourists, gondolas, or even movie extras. It’s a noirish maze of back canals, arched footbridges, time-blackened bricks and rat-infested sewers, reminiscent of The Third Man’s war-torn Vienna. In all, an ideal setting for ghostly glimpses of the couple’s daughter in a Red Riding Hood slicker. The creep factor rises whenever a pair of spinster sisters show up. One is blind but clairvoyant, and Christie quickly gets sucked in with hopes of reaching her dead child.

Christie is mostly in a faraway mental place while Sutherland, who alternates between two expressions — vacant stare and stupid grin — is difficult to read. He finally gets animated when he performs an astonishing midair, hold-your-breath stunt as a rain of multicoloured tiles clack on the church floor below. Like a rebuttal to the the film’s plodding tale,

Roeg employs a shock ending so audacious it must be seen to be believed. But lest his trickery be lost on slower viewers,

Sutherland spells it out with the line, “Nothing is as it seems.”