Loving Vincent is exactly what its title evokes, a ‘loving’. However, the word ‘loving’ is up for as much interpretation as the man himself. We don’t know if the word is in the present, past, or future progressive tense. We’re either in a state of currently loving Vincent, were loving, or will be loving. Grammatically, the title, in its simplicity, is as timeless as the art of Vincent van Gogh.

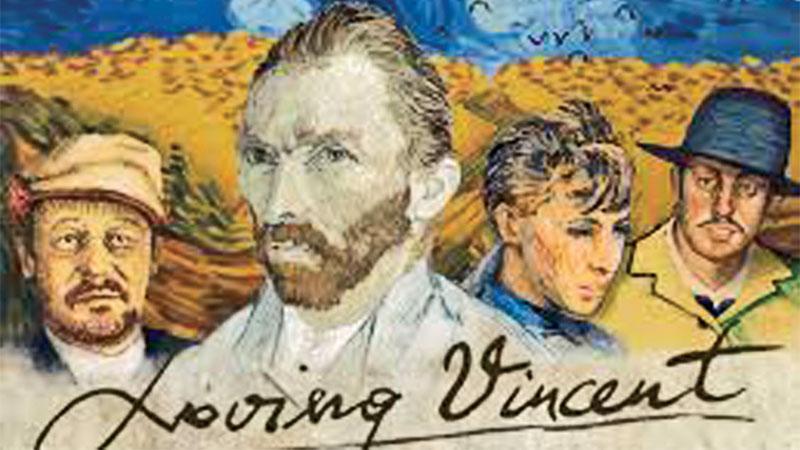

We begin the film a year after Van Gogh’s ‘apparent’suicide. Postman Joseph Roulin (Chris O’Dowd) — a subject of Van Gogh —has found an old letter from the artist to his brother Theo. The task to deliver this letter to Theo is given to Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth), the son of Joseph. The Postman and his son have two different views of Van Gogh, the father believing the artist to be a misunderstood and gentle man, and the son seeing the perceived weirdo. But as we travel through the film, we find how multilayered, emotionally fragile, and dedicated Van Gogh was.

The arc of the film is constructed of Armand’s retracing of Van Gogh’s steps, first to Paris, then to Auvers-sur-Oise. During this journey, the film switches between two stylisations of the artist’s work, for flashback scenes, charcoal is used, and for current events, paint is employed. Through many of the flashbacks, we see the darker and dead memories of the artist (making charcoal the perfect medium), as children throw rocks at him and he’s tutored/mocked by his ‘friend’, Rene Secretan.

Visual vibration

As the film progresses, Armand’s journey evolves from solely delivering the letter to understanding the circumstances of Van Gogh’s death. Armand is unsure of why/if the artist killed himself, as he was reported to be ‘cured’ of his melancholy and left no suicide note. Armand’s investigative scenes are brightly painted, as the animators astutely decided to not just animate Vincent’s paintings, but the textures of his brushstrokes too. The effect is that of visual vibration. As the colors shimmer and shake, we understand how the artist viewed the world, as not only static existence, but as vibrant action.

During Armand’s travels he meets many of the significant people in Van Gogh’s later life, all them at one point was one of his subjects, such as Adeline Ravoux (Eleanor Tomlinson), the proprietress of the inn the artist stayed in, the boatman (Aidan Turner), Marguerite Gachet (Saoirse Ronan), the daughter of Van Gogh’s doctor, and Dr. Gachet (Jerome Fliynn), the artist’s psychiatrist. Almost all of Vincent’s subjects loved him and counted him as a friend. The film paints Van Gogh, pun intended, as a lonely man. But when this support system was going well, he didn’t seem lonely.

Misunderstandings

The apparent happiness, the diligence to work, and the apparent support system are what deepens Armand’s belief that someone killed Van Gogh. Armand’s misunderstanding of the artist’s mental disease reflects misunderstandings that continue today. It’s still difficult to imagine seeing someone we think is happy be anything but. Even by the end of the film, we’re still not sure if Armand believes Dr. Gachet’s diagnosis of Van Gogh: that Vincent was a troubled man, who would never fully be over his disease, and needed only ‘small’ things to go wrong to retreat to his malady.

Instead, upon his return home, Armand tells his father that Vincent was killed and neglected to name those who shot him because he was too nice. We don’t know if Armand believes this, or if this is the lie he wants to tell, a final gift to Vincent.

That is, for people who loved him to still believe that he was getting better, in this case, Armand’s father. With this act, Armand deals in the same concealment that Vincent dealt with: the shielding of feelings to protect others. In this conspiratorial act, an act the audience participates in, we understand the artist far more than before, see him as a friend, mourn his death as thoughwe saw him yesterday, and take him with a handshake.