Title – Like the Flowing River

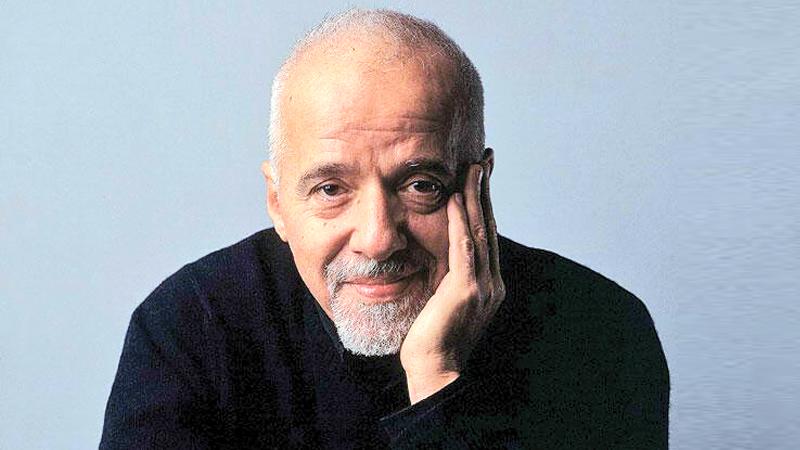

Author – Paulo Coelho

Translator – Margaret Jull Costa

Publisher – Harper Collins

Like the Flowing River is a collection of journalistic writings by Paulo Coelho, a world renowned Brazilian writer, and all of them have been published in various newspapers around the world. Though there are a 100 chapters in the book, most of them are little stories, anecdotes and thoughts on life.

As Paulo Coelho mentions in his preface to the book, “The pages that follow contain accounts of some of my own experiences, stories other people have told me, and thoughts I’ve had while travelling down particular stretches of the river of my life.”

Serious insights

The main characteristic of these writings is that they give serious insights into life, and that they enlighten the reader profoundly. The chapter below is a testament to it:

The main characteristic of these writings is that they give serious insights into life, and that they enlighten the reader profoundly. The chapter below is a testament to it:

“I reckon that it takes about three minutes to read each page in this book. Well, according to statistics, in that same space of time, 300 people will die, and another 620 will be born.

“I might take half an hour to write each page: I’m sitting at my computer, concentrating on what I’m doing, with books all around me, ideas in my head, cars driving past outside. Everything seems perfectly normal, and yet, during those thirty minutes, 3,000 people have died, and 6,200 have just seen the light of the world for the first time.”

Then, Coelho illustrates his view: “I stop and reflect a little. Perhaps many of those people were reaching the end of a long and painful illness, and some people are relieved when the Angel comes for them.

Then again, hundreds of those children who have just been born will be abandoned the next moment and will go on to form part of the death statistics before I have even finished writing this page.” (Page 105)

Philosophical writing

Coelho presents a simple statistic that he happened to read, but, through it, he profoundly enlightens the reader about the deaths and the births, the smiles and the tears of the world at the moment. In a way, it’s a philosophical writing which is similar to the Buddhist philosophy:

“I think to myself that I was once part of the birth statistic and will, one day, be included amongst the number of dead. It is good to be aware that I will die. Ever since I walked the road to Santiago, I have understood that, although life goes on and we are all eternal, this existence will one day end”.

“People do not think very much about death. They spend their lives worrying about absurdities; they put things off, and fail to notice important moments. They don’t take risks, because they think it’s dangerous. They complain a lot, but are afraid to take action. They want everything to change, but they themselves refuse to change.” (Page 106)

How does a writer be aware of another philosophy, here the Buddhist philosophy, without previously knowing it whatsoever? That is the universality of deep thinking about life.

Spiritual writing

Paulo Coelho, the author of the bestselling novel Alchemist, is generally regarded as a writer of spirituality. So, here too he focuses on spirituality at large. One example for it is the chapter of Rebuilding the House. There, he reflects on a friend of his who suffered from serious financial difficulties – he once tried to commit suicide because of those difficulties. But, once he saw a house in ruins and started to rebuild it, and when the renovation progressed, his personal life gradually starts to improve, resolving all the personal problems.

Paulo Coelho, the author of the bestselling novel Alchemist, is generally regarded as a writer of spirituality. So, here too he focuses on spirituality at large. One example for it is the chapter of Rebuilding the House. There, he reflects on a friend of his who suffered from serious financial difficulties – he once tried to commit suicide because of those difficulties. But, once he saw a house in ruins and started to rebuild it, and when the renovation progressed, his personal life gradually starts to improve, resolving all the personal problems.

Coelho writes about life, though some of the experiences in it cannot be resolved through scientific or logical thinking. The life consists of two parts which are the body and soul. Coelho , here, describes the function of the soul. He seems to think that if someone starts to do something with his inner feeling, the confusion of life or the personal problems of him would begin to end.

Journey of the book

Coelho mostly gives insightful thoughts on things around us. In the chapter titled Of Books and Libraries he says that he doesn’t own many books, and that he has only about 400 books in his personal library. Why is it so? He thinks that a book has its own journey: “My intention is not to save forests or to be generous. I simply believe that a book has its own journey to make, and should not be condemned to being stuck on a shelf.” (Page 62)

The Dead Man wore Pyjamas

In the chapter The Dead Man wore Pyjamas, he relates a story full of serious insights into life in Tokyo. Once Coelho was browsing on the Internet, and he happened to read a news item about a dead man. On June 10, 2004 the man was found dead in his pyjamas, in an abandoned multi-storied building in Tokyo City. According to the news item, Coelho reveals, the man died in his bedroom, and he was not murdered. The corpse was found by employees of a construction company on the second floor of a building in a housing development that was about to be demolished. So, we can figure out that the dead man in pyjamas, having failed to find somewhere to live in one of the most densely populated and most expensive places in the world, had simply decided to live in the building where he wouldn’t have to pay any rent.

When the man dies he was nothing more than a skeleton wearing pyjamas, and beside him, was an open newspaper dated February20, 1984. On a table nearby, the calendar also marked the same day. So, he had been there for twenty years! No one had noticed his absence. Finally, the dead man was identified as an ex-employee of the company who had built the housing development, where he had moved at the beginning of the 1980s, immediately after getting divorced. Moreover, he was just over fifty on the day he was reading the newspaper and suddenly departed this life. The Metropolitan Police revealed that his ex-wife had never tried to get in touch with him too. And as the construction company he worked for had gone bankrupt immediately after the project was finished, they also didn’t bother about checking whether he report for work or not.

Coelho gives his explanation on the death in the last paragraphs:

“When I finished reading the article, I kept thinking about that final sentence: the ex-wife was still alive; and yet, for twenty years, she had never once tried to contact him. What can have been going on inside her mind?”

“And then I thought about the dead man in pyjamas, about his complete and utter isolation, to the point that, for twenty long years, no one in the whole world had noticed that he had simply vanished without trace. I can only conclude that worse than hunger or thirst, worse than being unemployed, unhappy in love or defeated and in despair, far worse than any or all of those things, is feeling that no one, absolutely no one, cares about us.” (Page 39)

In this way, Coelho gives serious insights about life, more precisely isolation in a fast moving densely populated city. This kind of deep review can only be presented by a talented, serious writer. Paulo Coelho winds up his note on the dead man as follows: “Let us say a silent prayer for that man, and thank him for making us think about how important friends are.”