For the past few years, certain work culture trends have caused hundreds of millions of people to be exposed to the risks of overworking. In 2016, the number of people at risk of overworking was recorded by the WHO at 488 million worldwide, with 745,000 people dying from it that same year.

And while the pandemic has forced people to change their working lifestyles, the primary trends that have caused this uptick in overwork, namely remote work and gig-based work, have only accelerated.

And while the pandemic has forced people to change their working lifestyles, the primary trends that have caused this uptick in overwork, namely remote work and gig-based work, have only accelerated.

While this trend has been noticeable in countries all over the world, the toxic work culture that leads to overworking has been identified disproportionately in the Western Pacific and Southeast Asian regions.

The USA is reportedly the most overworked developed country in the world, with 85.8% of men and 66.5% of women working over the standard 35-40 hour work week.

The US is so far one of the few countries to not offer any paid maternity or family leave, and is the only high income country out of the ones that do not.

Though the current administration is attempting to amend this, even the proposed 12 weeks of paid leave is the very low end for developed countries. The US also has no legally mandated paid sick or annual leave nor does it have a set maximum work week length. America built its identity around the concept of capitalism, and the laws and regulations, or lack thereof, put in place surrounding work benefits it greatly at the cost of the common employee.

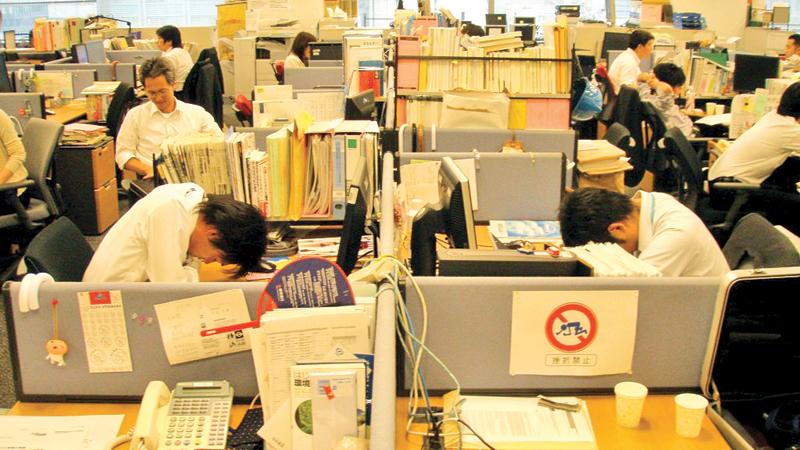

‘Karoshi’

While the threat of overwork snuck up on most nations, in Japan, the phenomenon of death due to overwork is so common and recognised, they’ve coined terms for it. ‘Karoshi’, or overwork death and ‘karōjisatsu’, suicide from overwork have been in public use by the country since the 80s.

While the threat of overwork snuck up on most nations, in Japan, the phenomenon of death due to overwork is so common and recognised, they’ve coined terms for it. ‘Karoshi’, or overwork death and ‘karōjisatsu’, suicide from overwork have been in public use by the country since the 80s.

At the height of this crisis, in 1988, surveys reported nearly 1/4th of the male employee population to be clocking 60-hour work weeks, well past the standard 40-hour weeks.

In spite of this awareness, any solutions proposed by the government only addressed symptoms instead of the cause.

‘Karoshi’ hotlines were set up and reforms were introduced to force employers to make their employees take holidays.

Japan also introduced a maximum work week length, a step above America, however, this length was still potentially fatal at 80 hours a week including special 100 hours a week month exceptions decided by the companies themselves.

Ultimately, while the issue of overworking is a crisis that primarily affects the Far West and the East, it’s still very much a growing problem for the rest of the world as well. The recessions most industries have suffered over the past year have forced most to take up overtime, usually unpaid.

Where the home used to serve as a sanctuary separate from work, thanks to teleworking, the boundaries of home and work have been blurred to the detriment of many people’s physical and mental health.

But more intrinsically, the toxic idea of “living to work” has been worming itself more into the minds of the world’s younger workforce. Without any broad reaching change, overwork and the multitude of issues that come with it is not only likely, but inevitable.