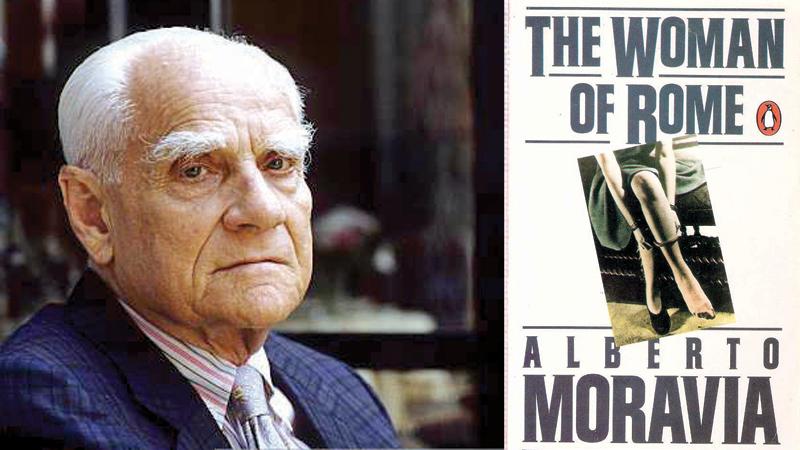

Alberto Moravia, pseudonym of Alberto Pincherle, is a major figure in 20th-century Italian literature. He was born on November 28, 1907, Rome, Italy, and died on September 26, 1990, Rome at the age of 82, Rome. Apart from being a veteran novelist, he was also an Italian journalist, short-story writer, playwright and a script writer.

His novels are known for fictional portrayals of social alienation and loveless sexuality. For a time, his novels and stories were declared immoral by the Vatican and placed on its Index of Forbidden Books. The Index was discontinued in the mid-1960’s amid the liberalizing reforms set into motion by the Second Vatican Council.

Moravia hadn’t had good school education. He contracted tuberculosis of the bone at the age of 8, was confined to bed for five years, and because of that he dropped out after nine years of schooling. Yet, he studied French, German, and English; read Giovanni Boccaccio, Ludovico Ariosto, William Shakespeare, and Molière; and began to write. His first novel, ‘Gli indifferenti’ (1929; Time of Indifference), is a scathingly realistic study of the moral corruption of a middle-class mother and two of her children. It became a sensation.

Moravia hadn’t had good school education. He contracted tuberculosis of the bone at the age of 8, was confined to bed for five years, and because of that he dropped out after nine years of schooling. Yet, he studied French, German, and English; read Giovanni Boccaccio, Ludovico Ariosto, William Shakespeare, and Molière; and began to write. His first novel, ‘Gli indifferenti’ (1929; Time of Indifference), is a scathingly realistic study of the moral corruption of a middle-class mother and two of her children. It became a sensation.

Some of his more significant novels are ‘Agostino’ (1944; Two Adolescents); ‘La Romana’ (1947; The Woman of Rome); ‘La disubbidienza’ (1948; Disobedience); and ‘Il conformista’ (1951; The Conformist), all of which are of themes of isolation and alienation. Another two noted novels are ‘La ciociara’ (1957; Two Women) which tells of an adaptation to post-World War II Italian life, ‘La noia’ (1960; The Empty Canvas), a story of a painter unable to find meaning either in love or work. Many of Moravia’s books were made into motion pictures as well.

His books of short stories include ‘Racconti romani’ (1954; Roman Tales) and ‘Nuovi racconti romani’ (1959; More Roman Tales). ‘Racconti di Alberto Moravia’ (1968) is a collection of earlier stories. Later short-story collections include ‘Il paradiso’ (1970; Paradise) and ‘Boh’ (1976; The Voice of the Sea and Other Stories). And his views on literature and realism are expressed in two books which are a stimulating book of essays, ‘L’uomo come fine’ (1963; Man as an End), and his autobiography, ‘Alberto Moravia’s Life’, was published in 1990.

His art of fiction is best described in a Paris Review interview. There, he was interviewed by Anna Maria de Dominicis and Ben Johnson, and the following are excerpts from the interview:

“I write about what I know”

.my works are not autobiographical in the usual meaning of the word…. whatever is autobiographical is so in only a very indirect manner, in a very general way. I am related to Girolamo (protagonist in “Inverno di malato”), but I am not Girolamo. I do not take, and have never taken, either action or characters directly from life. Events may suggest events to be used in a work later; similarly, persons may suggest future characters; but suggest is the word to remember. One writes about what one knows. For instance, I can’t say I know America, though I’ve visited there. I couldn’t write about it. Yes, one uses what one knows, but autobiography means something else. I should never be able to write a real autobiography; I always end by falsifying and fictionalizing—I’m a liar, in fact. That means I’m a novelist, after all. I write about what I know.

Do not to criticize

There’s no question of influence, certainly. Furthermore, Svevo (an Italian writer) was a conscious critic of the bourgeoisie; my own criticism, whatever there is, is unintentional, occurring entirely by chance. In my view, the function of a writer is not to criticize anyway; only to create living characters. Just that.

….. I write simply to amuse myself; I write to entertain others and—and, well, to express myself. One has one’s own way of expressing oneself, and writing happens to be mine.

A writer survives despite his beliefs

Social criticism must necessarily, and always, be an extremely superficial thing. But don’t misunderstand me. Writers, like all artists, are concerned with representing reality, to create a more absolute and complete reality than reality itself. They must, if they are to accomplish this, assume a moral position, a clearly conceived political, social, and philosophical attitude; in consequence, their beliefs are, of course, going to find their way into their work. What artists believe, however, is of secondary importance, ancillary to the work itself. A writer survives in spite of his beliefs. Lawrence will be read whatever one thinks of his notions on sex. Dante is read in the Soviet Union.

Characters

(Have there been times when characters have got out of hand?) Not in anything I’ve published. Whenever characters get out of control, it’s a sign that the work has not arisen from genuine inspiration. One doesn’t go on then.

(Have there been times when characters have got out of hand?) Not in anything I’ve published. Whenever characters get out of control, it’s a sign that the work has not arisen from genuine inspiration. One doesn’t go on then.

Not pre-prepared

(Did you work from notes on La Romana? Rumour has it…) Never. I never work from notes. I had met a woman from Rome — ten years before. Her life had nothing to do with the novel, but I remembered her, she seemed to set off a spark. No, I have never taken notes or ever even possessed a notebook. My work, in fact, is not prepared beforehand in any way. I might add, too, that when I’m not working I don’t think of my work at all. When I sit down to write — that’s between nine and twelve every morning, and I have never, incidentally, written a line in the afternoon or at night — when I sit at my table to write, I never know what it’s going to be till I’m under way. I trust in inspiration, which sometimes comes and sometimes doesn’t. But I don’t sit back waiting for it. I work every day.

Experience

For the psychology of my characters, and for every other aspect of my work, I draw solely upon my experience; but understand, never in a documentary, a textbook, sense. No, I met a Roman woman called Adriana. Ten years afterward I wrote the novel for which she provided the first impulse. She has probably never read the book. I only saw her that once; I imagined everything, I invented everything.

Imagination or fantasy

Don’t confuse imagination and fantasy; they are two distinct actions of the mind. Benedetto Croce makes a great distinction between them in some of his best pages. All artists must have imagination, some have fantasy. Science fiction, or — well, Ariosto . . . that’s fantasy. For imagination, take Madame Bovary. Flaubert has great imagination, but absolutely no fantasy.

No negative characters

I have no negative characters. I don’t think it’s possible to write a good novel around a negative personality. For some of my characters I have felt affection, though.

Each book is reworked

Each book is worked over several times. I like to compare my method with that of painters centuries ago, proceeding, as it were, from layer to layer. The first draft is quite crude, far from being perfect, by no means finished; although even then, even at that point, it has its final structure, the form is visible. After that I rewrite it as many times—apply as many “layers”—as I feel to be necessary.