The audience on the sun-kissed verandah was unsurprised when award-winning author and planter Herman Gunaratne recounted what a former British governor-general confided in him: “Ceylon is the most prized possession Britain ever had.” Overhead, on the first floor was an entire abode dedicated to cinnamon – waiting to be experienced and explored.

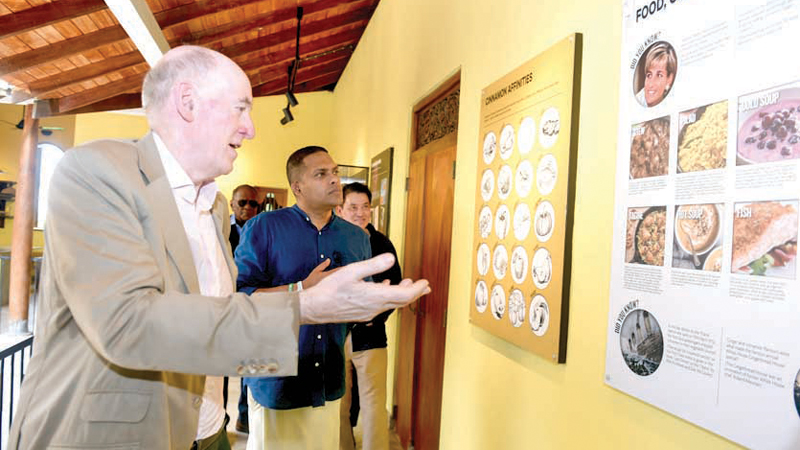

Minister of Tourism and Lands and Minister of Sports and Youth Affairs Harin Fernando addressing the gathering at the opening of the Cinnamon Museum

Such is how Sri Lanka’s fragrant history took centre-stage at the Mirissa Hills estate recently. A once-abandoned cinnamon plantation is now transformed into a tourist destination. Of course, thanks to Art historian Miles Young who spotted the land decades ago and was enamoured by its beauty. The land was like no other, and Young was determined to take on the task of reviving it.

And the rest is history as the public can now step into the world’s first Cinnamon Museum. Housed in Mirissa Hills, the museum shares the secrets of cinnamon, a spice treasured across the globe.

Tourism boost

Despite a packed schedule, which involved inaugurating the 100th-anniversary celebrations of Udarata Menike, Minister of Tourism and Lands and Minister of Sports and Youth Affairs Harin Fernando made it a priority to attend the opening of the Cinnamon Museum. Minister Fernando said that the country’s tourism industry has been too narrow in its focus. He said that Sri Lanka has not even shown tourists 20 percent of what Sri Lanka has to offer. Fernando said that the industry relies too heavily on regular destinations, citing popular beach spots such as Mirissa and Weligama, as well as well-known historical sites such as Sigiriya and Arugam Bay.

The Minister expressed particular pride in Sri Lanka’s position as the world’s largest cinnamon exporter. He lauded the Cinnamon Museum as a brilliant idea and a product the country can be proud of. Minister Fernando’s narrative signalled a desire for a more innovative approach to Sri Lanka’s tourism sector. He encouraged similar initiatives that display the country’s diverse attractions, believing it will benefit the nation in the long run.

When Mirissa Hills Proprietor Miles Young acquired the abandoned property and set about replanting cinnamon, he employed local labour and revived the age-old practice of peeling. In this cinnamon estate, Young could foresee more than just a working plantation. He decided to capitalise on his own background as an art historian.

Research gaps

Mirissa Hills Proprietor Miles Young addressing the gathering

Miles into cinnamon research, Young identified various gaps and shortcomings in knowledge. Well-documented records of cinnamon’s historical significance in trade and culture were scarce. Young was inspired to share the stories and secrets of cinnamon. And he wasted no time.

Mirissa Hills accommodates the museum and also welcomes visitors to stay in a bungalow overlooking the estate. The plantation stands apart for cultivating the prized ‘true’ cinnamon variety. Young observes cinnamon as an under-exploited asset for tourism. Through the museum and estate experiences, he aims to educate visitors on the distinction between ‘true’ cinnamon and its inferior substitutes. His ultimate objective is to bring alive the spice’s rich history, romantic allure, and captivating legends.

Cinnamon is a common spice that readily graces our kitchens. Yet, how it is transported from the plantation to pantry often remains a mystery. Young’s introductory lecture sought to bridge this gap, exploring the complexities of cinnamon’s narrative. Young’s brief lecture elucidated the gap between our enjoyment of cinnamon and our understanding of its rich history and production.

This disconnect, Young said, extends to those directly involved in cinnamon cultivation. Many workers, he noted, remain unaware of the diverse uses and historical significance of the spice they harvest. The museum’s curated exhibits aim to rectify this, educating visitors about the intricate processes involved in cinnamon production and its cultural and historical context.

Cinnamon is more than just a flavour enhancer, said historian Young. Exhibits and interactive displays throughout the museum paint a picture of cinnamon as a symbol of prosperity, love, and warmth, holding a unique position compared to other spices such as pepper or cardamom.

The museum, designed by architect C Anjalendran, ventures on a journey through time. Exhibits, artwork, and informative displays decode the history and cultural lustre of cinnamon. From its ancient use in Egyptian embalming rituals to its modern-day applications in cuisine and medicine, the museum traces one fascinating story that claims to be cinnamon’s.

The museum’s narrative extends beyond mere facts and figures. Live demonstrations showcase the traditional techniques of cinnamon peeling, offering visitors a chance to witness this age-old practice firsthand. The comprehensive visitors’ centre offers immersive experiences for tourists and locals alike. Guided tours begin with the earliest recorded uses of cinnamon and trace its path to modern Sri Lanka.

The visitors have the opportunity to learn about the establishment of cinnamon estates in what was once known as Ceylon, and survey the subtleties of Sri Lanka’s long history as a leading cinnamon exporter.

A particular focus is placed on Sri Lanka’s historical role as a leading producer and exporter of cinnamon. Visitors can study the traditional methods of harvesting, peeling, and preparing cinnamon through interactive exhibits.

Dedicated to true cinnamon, scientifically known as Cinnamomum Zeylanicum, the museum invites visitors on a sensory journey to explore the origins and evolution of this prized variety native to Sri Lanka.

As a member of the laurel family, cinnamon requires a meticulous cultivation process. Visitors can learn about the intricacies of growing these cinnamon trees, followed by the careful peeling of their branches to reveal the coveted inner bark. This inner bark, rich in the compound cinnamaldehyde, serves as the spice’s active ingredient. It imparts its distinct flavour and possesses potential therapeutic benefits.

Cinnamon’s rival

Cassia is a competing spice that comes from a larger tree. It is botanically distinct from true cinnamon. While both contain cinnamaldehyde, the key flavour component, cassia lacks the potency of true cinnamon and raises concerns due to its higher coumarin content. The European Union has cautioned against excessive cassia consumption due to potential health risks.

However, Young’s museum doesn’t demonise cassia entirely. Properly labelled, cassia has its place, but the museum aims to advocate against misrepresentation and empower consumers to make informed choices. After all, cinnamon and cassia have a long history of confusion, with some products being erroneously marketed simply as cinnamon.

The museum explores Cinnamon’s fascinating journey through time. Cinnamon has experienced three significant periods of demand, sponsored by empires and civilisations. It played a role in ancient rituals, served as a prized perfume in Egypt, and became a coveted commodity sought after by the Romans. However, historical records also reveal a counterpoint – puritanical opposition to cinnamon imports during certain eras.

Europe’s medieval period saw a rise in demand for luxury goods such as cinnamon owing to colonisation and economic growth. However, the Arab world held a tight grip on the spice route, shaping Sri Lanka’s role in the supply chain. The Seligama caste emerged as the primary gatherers, commissioned to harvest cinnamon.

Cinnamon trade

Subsequent chapters in history saw European powers vying for control of the cinnamon trade. Portuguese dominion enriched Lisbon. The Dutch manipulated prices and suppressed rebellions such as the Chalia revolts. Enter the British, and it was a period of both opportunity and challenge. Demand for cinnamon soared alongside the competition. Free trade movements and the Napoleonic invasion of Holland disrupted established systems and caused the spice’s prominence to decline. Many cinnamon estate owners were forced to sell their land or diversify their crops.

Young also made references to cinnamon’s association with romance. From Cleopatra’s legendary use of cinnamon to enhance her allure to the romantic musings of novelist Barbara Cartland, the spice has long been associated with seduction and love. The museum suggests that pumpkin pie, infused with the warm aroma of cinnamon, might be the world’s most romantic food. Potions and elixirs infused with cinnamon were believed to possess potent mystical properties.

The museum’s display of Michael Ondaatje’s poem The Cinnamon Peeler takes a unique approach. It’s set up in a circular format, inviting visitors to follow a winding path as they read the poem. The poem reflects Ondaatje’s intense and somewhat obsessive desire, exploring how cinnamon’s fragrance, warmth, and sweetness can evoke sensuality.

The first two verses of the poem express the sensuality of a love poem. The speaker’s intense desire for their beloved is evident from the start with the line “If I were a cinnamon peeler,” creating a world driven by the speaker’s desires. The cinnamon scent becomes so pervasive that the woman wouldn’t be able to hide it – “you could never walk through markets” without revealing the speaker’s touch.

Literary references

One of the earliest English references to cinnamon is found in Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. In the Wife of Bath’s Prologue, she describes her deceased husbands, noting that the fifth “was a worthy landowner who loved me best of all with spices.” Chaucer links cinnamon with wealth and social status, highlighting its rarity and value in medieval Europe. References to cinnamon appear throughout The Canterbury Tales, including Chaucer’s medieval English phrase “My faire bryd, my sweetecynamome?” in The Miller’s Tale, which translates to “My fair bird, my sweet cinnamon?” in modern English.

Cinnamon’s association with luxury continues in William Shakespeare’s works. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Oberon, the king of the fairies, instructs Puck to fetch a flower “whose juice is on Cupid’s fiery shaft,” describing it as “sweet-smelling” and “eminent in hue.” This description suggests the flower is a metaphor for cinnamon, linking its sweet aroma to the passionate heat of love.

In Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, the protagonist strikes a deal with the devil, exchanging his soul for worldly pleasures. Mephistopheles, the devil, conjures a lavish feast for Faustus, including “celestial food, manna, and dates, drugs of the Indies, and eunuchs’ flesh.” Cinnamon is mentioned alongside other exotic and potentially dangerous substances, suggesting its association with the forbidden and the potential consequences of excessive indulgence.

John Milton depicts Satan’s fiery presence in Paradise Lost, describing him as having “the fair face and counterfeit of heaven… Yet all his nature changed for anger and spite. Thenceforth to be destin’d miserable.” The subtle warmth of cinnamon can be interpreted as a distorted reflection of Satan’s fallen grace.