Roy’s first novel in 20 years is a sprawling but memorable tale involving a vast cast

The drama of the unforthcoming second novel is often a great deal more intense and traumatic to literary onlookers than it is to their putative creators. Marilynne Robinson, for example, whose output as a novelist paused for nearly 25 years after her brilliant debut Housekeeping, published in 1980; when it recommenced, with Gilead, it did so in Pulitzer prize-winning fashion, and two subsequent novels. But this was not writer’s block, it was a writer making choices; the academic work and essays that Robinson undertakes as well as her fiction writing are just as much a part of her creative and intellectual identity.

Five years

Even when there seems to be a more straightforward matter of a writer moving slowly – as in, for example, Nadeem Aslam’s Maps for Lost Lovers, which took a decade to write – it is revealed to be more a case of endeavour and precision rather than existential crisis (it took him five years to get the opening chapter right).

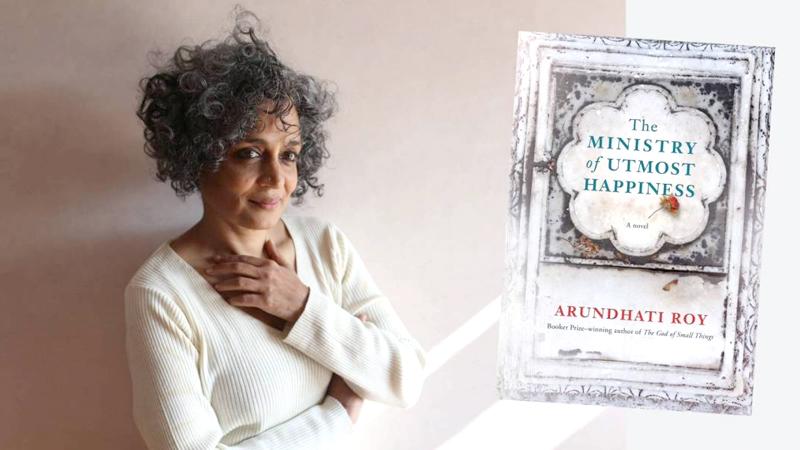

In the case of Arundhati Roy, whose debut novel The God of Small Things won the Booker prize in 1997, her life as a political activist more than explains what she has been doing in the intervening two decades: protesting against ecological depredations, on behalf of Kashmir independence and against Hindu nationalism, as well as fighting charges of sedition laid against her by the Indian government, left her little free time. Her prolific career as a writer of nonfiction, from 2002’s The Algebra of Infinite Justice to books on capitalism, globalisation and democracy, has brought her to the fore as a polemicist and political philosopher.

But there is something Janus-faced about the way we fetishise the writing of fiction: Roy is at once seen to be participating in the “real world” but also as having abandoned – or been abandoned by – the creative muse that we imagine propels all artists. Her recent interview with the Guardian’s Decca Aitkenhead, in which she said: “To me, there is nothing higher than fiction. Nothing. It is fundamentally who I am. I am a teller of stories. For me, that’s the only way I can make sense of the world, with all the dance that it involves”, suggests that she would not agree with that binary worldview. And neither, indeed, does her second novel.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is a curious beast: baggy, bewilderingly overpopulated with characters, frequently achronological, written in an often careless and haphazard style and yet capable of breathtakingly composed and powerful interludes. The idea that the personal is political and vice versa informs its every sentence, but it also interrogates that assumption, examining its contours and consequences. We begin with Anjum, who has taken up residence, for reasons that gradually unfold, in a graveyard, where she lives “like a tree” (part of the natural world, unspeaking, all-seeing is one interpretation; attempting to avoid notice another), but also as a “mehfil”, “a gathering of everybody and nobody, of everything and nothing.

Is there anybody else you would like to invite? Everyone’s invited.” And indeed, over the course of the novel, Anjum’s graveyard home comes to function as a secular, or at least multifaith, sanctuary, protected by willpower from the turbulent outside world.

The word that more frequently attaches to Anjum is “hijra”, a Hindu word that variously translates as hermaphrodite (Anjum, born Aftab, herself has both male and female sex organs, until she undergoes surgery), eunuch, third gender and transgender person. From early adolescence, Anjum has lived in the Khwabgah, which can mean, straightforwardly, sleeping quarters, or house or palace of dreams; for her, it has been the latter, a place of liberation and self-expression.

Caught up in a massacre

The other hijras who live there form a family, even those who, like Saeeda, “could speak the new language of the times – she could use the terms cis-Man and FtoM and MtoF”, and in doing so edges Anjum – one of “the old exotics” – out of the “Number One spot in the media”.

But not far into the novel, the faint hint of Tales of the City departs. On a visit to a Gujarati shrine, Anjum is caught up in a massacre of Hindu pilgrims and subsequent government reprisals against Muslims, and retreats – at least temporarily shedding her brightly coloured clothing for a more masculine Pathan suit – to the graveyard. Her immurement, however, signals the novel’s sprawling expansion.

It takes us from Delhi to Kashmir, where India and Pakistan wage war around the Line of Control, turning inhabitants of perhaps the world’s most beautiful valley into fugitives, jihadis, martyrs, informants and – as in the woman who dies only after a bullet has passed through her daughter’s skull into her heart – victims. As a campaigner for Kashmiri independence, Roy is more than alive to its complexities, as one of her more detached characters, an Indian diplomat, notes: “Their problem is not confusion, not really. It’s more like a terrible clarity that exists outside the language of modern geopolitics. All the protagonists on all sides of the conflict, especially us, exploited this fault line mercilessly. It made for a perfect war – a war that can never be won or lost, a war without end.”

It has become something of a cliche to talk about contemporary Indian novels written in English as refracting the Victorian panorama of Dickens, or of co-opting the tropes of magical realism to invoke the continuing pull of traditional beliefs in a country that defined itself on the basis of its secularism. But in truth, these literary influences are more subverted than they are copied; claimed, in the service of encompassing a society too vast and diverse ever to be viewed through a single lens.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is a novel of maddeningly frayed edges, wonky pacing and occasional longueurs. But its patchwork of narratives, painful, funny, sexy, violent, earthy, otherworldly, its recurring images of lost and recovered children, individual sacrifice and self-denial, and its depiction of the constant battle toward self-assertion in a society still held in thrall to the taxonomy of caste and class, make for a disturbing and memorable return to the land of make-believe.