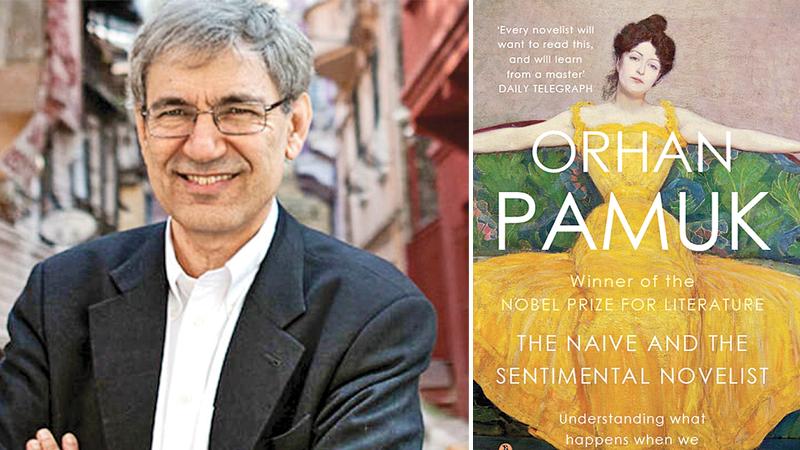

Author – Orhan Pamuk

Translator – Nazim Dikbas

Publisher – Hamish Hamilton of Penguin Books

Pages – 200

This is a collection of essays on the art of reading and writing a novel by Orhan Pamuk, the Nobel Prize winning Turkish novelist in 2006. These essays were originally presented as the Charles Eliot Norton lectures at Harvard University in 2009, and here he compiles them to give new insights on how we read and write a novel.

He touches on the work of many earlier critics, including Nabokov, E.M. Forster and Friedrich Schiller, whose 1795 essay “On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry” inspired his title.

The floppy of the book describes the content of it briefly:

“What happens within us when we read a novel? And how does a novel create its unique effects, so distinct from those of a painting, a film, or a poem? In this inspired, thoughtful, deeply personal book, Orhan Pamuk takes us into the worlds of the writer and the reader, revealing their intimate connections.

“Pamuk draws on Friedrich Schiller’s famous distinction between “naive” poets – who write spontaneously, serenely, unselfconsciously – and “sentimental” poets: those who are reflective, emotional, questioning and alive to the artifice of the written word. Harking back to the beloved novels of his youth and ranging through the work of such writers as Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Stendhal, Flaubert, Proust, Mann and Naipaul, he explores the oscillation between the naive and the reflective, and the search for an equilibrium, that lie at the centre of the novelist’s craft.

He ponders the novel’s visual and sensual power – its ability to conjure landscapes so vivid they can make the here-and-now fade away. In the course of this exploration, he considers the elements of character, plot, time and setting that compose the “sweet illusion” of the fictional world.

“Anyone who has known the pleasure of becoming immersed in a novel will enjoy, and learn from, this perceptive book by one of the modern masters of the art.”

Six chapters

The book has six chapters which are What our mind do when we read novels, Mr. Pamuk, did all this really happen to you?, Literary character, plot, time, Words, pictures, objects, Museums and novels, The center. First chapter elaborates the general idea of the novel and what happens when we read a novel:

“Novels are second lives. Like the dreams that the French poet Gérald de Nerval speaks of, novels reveal the colours and complexities of our lives and are full of people, faces and objects we feel we recognise. Just as in dreams, when we read novels, we are sometimes so powerfully struck by the extraordinary nature of the things we encounter that we forget where we are and envision ourselves in the midst of the imaginary events and people we are witnessing.

At such times, we feel that the fictional world we encounter and enjoy is more real than the real world itself. That these second lives can appear more real to us than reality often means that we substitute novels for reality, or at least that we confuse them with real life. But we never complain of this illusion, this naïveté.

On the contrary, just as in some dreams, we want the novel we are reading to continue and hope that this second life will keep evoking in us a consistent sense of reality and authenticity. In spite of what we know about fiction, we are annoyed and bothered if a novel fails to sustain the illusion that it is actually real life.” (Page 3)

In this chapter, Pamuk lists out nine operations that our mind performs when we read a novel. There he says when we read a novel, “our usual operation is to follow the narrative and try to figure out the meaning and main idea that are suggested by the things we encounter.”

Then he describes “As we picture in our imagination what the words are telling us (what they want to tell us), we readers complete the story. In doing this, we propel our imagination by searching for what the book says or what the narrator wants to say, what he intends to say, what we guess he is saying – in other words, by searching for the novel’s center.”

Non-Cartesian logic

According to Pamuk, to read a novel is to wonder constantly, even at moments when we lose ourselves most deeply in the book. And he says “Reading a novel means understanding the world via a non-Cartesian logic.” At last he reveals that the searching of the novel’s secret center is the most frequent operation our mind performs when we read a novel, whether naively unaware or sentimentally reflective.

In the third chapter, Literary character, Plot, Time he unfolds, “Like many people, I believe that Shakespeare is responsible for our conception of the modern fictional character, developed initially in a broad range of literary writings and later in the nineteenth – century novel.

Shakespeare and Shakespeare criticism in particular, helped the fictional character to evolve from its centuries – old definition – the embodiment role, historical or symbolic in nature (despite Moliere’s brilliant wit, the protagonist of his play The Miser is always and only a miser) – and transformed it into a complex entity shaped by conflicting impulses and conditions.” (Page 63)

In this way, he describes the nature and role of a character in fiction. There he says, “The author’s identification with heroes of his books has a childlike quality to it, especially during the sentence – by – sentence process of writing. Childlike, but not naïve. My mood, as I identify with each of my heroes, resembles what I used to feel when I played alone as a child. Like all children, I like to play make – believe, to put myself in someone else’s place and imaging dream worlds in which I was a soldier, a famous soccer player, or a great hero.” (Page 70)

Here he elaborates art of the novel writing. In the fourth chapter, Words, Pictures, Objects he presents the components of novel, such as words, pictures and objects with regard to classical novels, such as Anna Karenina, his own novel My Name is Red, Nana by Emil Zola. He said, “Tolstoy does not tell us what Anna’s feelings are as she rides on the St. Petersburg train. Instead, he paints pictures that help us to feel these emotions: the snow visible from the window on the left, the activity in the compartment, the cold weather and so on.” (Page 104)

The book ends with a personal epilogue by Pamuk where he states how he became a novelist. There he says as follows:

“….. Since I delivered these lectures at Harvard, I have been asked repeatedly, ‘Mr. Pamuk, are you a naïve novelist or a sentimental one?’ I would like to emphasise that, for me, the ideal state is one in which the novelist is naive and sentimental at the same time.” (Page 189)

Compiled by Ravindra Wijewardhane