Christians around the world celebrate the glorious feast of the ‘Nativity - Jesus’ Birth on December 25. The times have been defined by a pandemic and it is amid the modalities of social living during the Covid-19 that this Christmas sails past. In the liturgical year, Christmas is preceded by the season of Advent and initiates the Christmastide, which lasts twelve days.

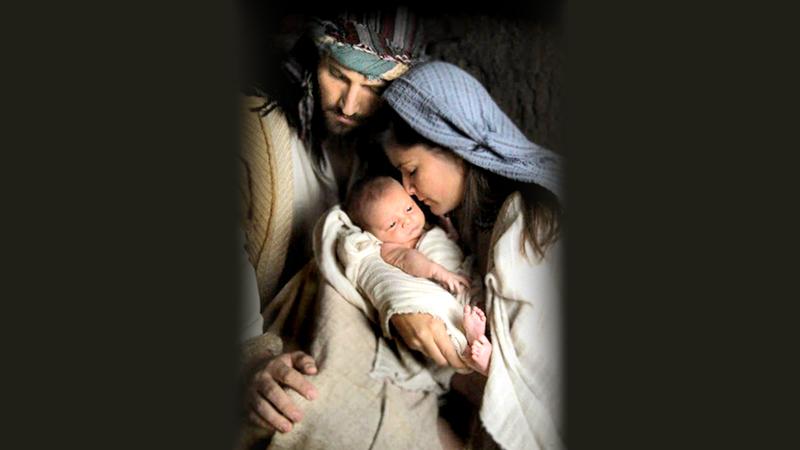

The traditional Christmas narrative, the Nativity of Jesus, delineated in the New Testament says that Jesus Christ was born in Bethlehem. When Joseph and Mary arrived in the city, the inn had no room and so they were offered a stable where the Christ Child was soon born, with angels proclaiming this news to shepherds who then further disseminated the information.

The traditional Christmas narrative, the Nativity of Jesus, delineated in the New Testament says that Jesus Christ was born in Bethlehem. When Joseph and Mary arrived in the city, the inn had no room and so they were offered a stable where the Christ Child was soon born, with angels proclaiming this news to shepherds who then further disseminated the information.

Christmas Day is celebrated religiously by a majority of Christians, as well as culturally by many and forms an integral part of the holiday season centered on it. The feast is characterised by special liturgies, joyful carols, brightly wrapped gifts and festive food. This article traces how December 25 came to be associated with Jesus’ birthday and the history that revolves around Christmas during the past 2020 years.

Etymology

‘Christmas’ is a shortened form of ‘Christ’s mass’. The word is recorded as Crīstesmæsse in 1038 and Cristes-messe in 1131. Crīst (genitive Crīstes) is from Greek Khrīstos, a translation of Hebrew Māsia, ‘Messiah,’ meaning ‘anointed’ and ‘mæsse’ is from the Latin missa, the celebration of the Eucharist.

The form ‘Christenmas’ was also historically used, but is now considered archaic and dialectal. The term derives from Middle English Cristenmasse, meaning ‘Christian mass’. Xmas is an abbreviation of Christmas found particularly in print, based on the initial letter chi in Greek Khrīstos, “Christ” though numerous style guides discourage its use.

Jesus’ birth

There is no mention of birth celebrations in the writings of early Christian writers such as Irenaeus (c. 130–200) or Tertullian (c. 160–225). Origen of Alexandria (c. 165–264) goes so far as to mock Roman celebrations of birth anniversaries - a strong indication that Jesus’ birth was not celebrated at all at this point.

This stands in sharp contrast to the very early traditions surrounding Jesus’ last days. Each of the Four Gospels provides detailed information about the time of Jesus’ death. According to John, Jesus is crucified just as the Passover lambs are being sacrificed. In Matthew, Mark and Luke, the Last Supper is held after sundown and Jesus is crucified the next morning.

Easter was simply the gradual Christian reinterpretation of Passover in terms of Jesus’ Passion. Its observance could even be implied in the New Testament (1 Corinthians 5:7–8: “Our paschal lamb, Christ, has been sacrificed. Therefore let us celebrate the festival…”); it was certainly a distinctively Christian feast by the mid-second century C.E., when the Epistle to the Apostles has Jesus instruct his disciples to “make commemoration of [his] death, that is, the Passover.”

Jesus’ ministry, miracles, Passion and Resurrection were often of most interest to firstand earlysecond-century C.E. Christian writers. But over time, Jesus’ origins would become of increasing concern. We can begin to see this shift already in the New Testament. The earliest writings of Paul and Mark make no mention of Jesus’ birth. The Gospels of Matthew and Luke provide well-known accounts of the event.

In the second century C.E., further details of Jesus’ birth and childhood are related in apocryphal writings such as the Infancy Gospel of Thomas and the Proto-Gospel of James. These texts provide everything from the names of Jesus’ grandparents to the details of his education but not the date of his birth.

Finally, in about 200 C.E., a Christian teacher in Egypt makes reference to the date Jesus was born. According to Clement of Alexandria, several different days had been proposed by various Christian groups. Clement writes: “There are those who have determined not only the year of our Lord’s birth, but also the day; and they say that it took place in the 28th year of Augustus, and in the 25th day of Pachon.

And treating of His Passion, with very great accuracy, some say that it took place in the 16th year of Tiberius, on the 25th of Phamenoth [March 21]; and others on the 25th of Pharmuthi [April 21] and others say that on the 19th of Pharmuthi [April 15] the Saviour suffered. OSthers say that He was born on the 24th or 25th of Pharmuthi [April 20 or 21].”

The earliest mention of December 25 as Jesus’ birthday comes from a mid-fourth century Roman almanac. The first date listed, December 25, is marked: “Christ was born in Bethlehem of Judea.” In about 400 C.E., Augustine of Hippo mentions a local dissident Christian group, the Donatists, who apparently kept Christmas festivals on December 25.

Clearly there was great uncertainty, but also a considerable amount of interest, in dating Jesus’ birth in the late second century. By the fourth century, however, we find references to two dates that were widely recognised and now also celebrated as Jesus’ birthday: December 25 in the Western Roman Empire and January 6 in the East. For most Christians, December 25 would prevail, while January 6 eventually came to be known as the Feast of the Epiphany.

So, almost 300 years after Jesus was born, we finally find people observing his birth in mid-winter. There are two theories today: one extremely popular, the other less often heard outside scholarly circles, though far more ancient.

First Christmas celebration

The most loudly touted theory about the origins of the Christmas date is that it was borrowed from pagan celebrations. Christmas, the argument goes, is really a spin-off from these pagan solar festivals. According to this theory, early Christians deliberately chose these dates to encourage the spread of Christmas and Christianity throughout the Roman world.

Despite its popularity, this theory of Christmas’s origins has its problems. It is not found in any ancient Christian writings. The church father Ambrose (c. 339–397), described Christ as the true sun, who outshone the fallen gods of the old order. But early Christian writers never hint at any recent calendric engineering; they clearly don’t think the date was chosen by the church.

It’s not until the 12th century that we find the first suggestion that Jesus’ birth celebration was deliberately set at the time of the pagan feasts. A marginal note on a manuscript of the writings of the Syriac biblical commentator. Dionysius bar-Salibi, states that in ancient times the Christmas holiday was actually shifted from January 6 to December 25.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Bible scholars spurred on by the new study of comparative religions latched on to this idea. They claimed that because the early Christians didn’t know when Jesus was born, they simply assimilated the pagan solstice festival for their own purposes, claiming it as the time of the Messiah’s birth and celebrating it accordingly.

More recent studies have shown that many of the holiday’s modern trappings do reflect pagan customs borrowed much later, as Christianity expanded into Northern and Western Europe. The Christmas tree, for example, has been linked with late medieval druidic practices. This has only encouraged modern audiences to assume that the date, too, must be pagan.

Most significantly, the first mention of a date for Christmas (c. 200) and the earliest celebrations that we know about (c. 250–300) come in a period when Christians were not borrowing heavily from pagan traditions of such an obvious character.Yet, in the first few centuries C.E., the persecuted Christian minority was greatly concerned with distancing itself from the larger, public pagan religious observances, such as sacrifices, games and holidays. This was still true as late as the violent persecutions of the Christians conducted by the Roman emperor Diocletian between 303 and 312 C.E.

This would change only after Constantine converted to Christianity. From the mid-fourth century on, we find Christians deliberately adapting and christianising pagan festivals. A famous proponent of this practice was Pope Gregory the Great, who, in a letter written in 601 C.E. to a Christian missionary in Britain, recommended that pagan temples be converted into churches.

At this late point, Christmas may well have acquired some pagan trappings. But we don’t have evidence of Christians adopting pagan festivals in the third century, at which point dates for Christmas were established. Thus, it seems unlikely that the date was simply selected to correspond with pagan solar festivals.

Birth and Death

There is another way to account for the origins of Christmas. Strange as it may seem, the key to dating Jesus’ birth may lie in the dating of Jesus’ death at Passover. This view was first suggested to the modern world by French scholar Louis Duchesne in the early 20th century and fully developed by American Thomas Talley in more recent years. But they were certainly not the first to note a connection between the traditional date of Jesus’ death and his birth.

Around 200 C.E. Tertullian of Carthage reported the calculation that the 14th of Nisan (the day of the crucifixion according to the Gospel of John) in the year Jesus died was equivalent to March 25 in the Roman calendar. March 25 is, of course, nine months before December 25; it was later recognised as the Feast of the Annunciation. Thus, Jesus was believed to have been conceived and crucified on the same day of the year. Exactly nine months later, Jesus was born, on December 25.

Augustine, too, was familiar with this association. In On the Trinity (c. 399–419) he writes: “For Jesus is believed to have been conceived on March 25, upon which day also he suffered; so the womb of the Virgin, in which he was conceived, where no one of mortals was begotten, corresponds to the new grave in which he was buried, wherein was never man laid, neither before him nor since. But he was born, according to tradition, upon December 25.”

It reflects ancient and medieval understandings of the whole of salvation being bound up together. One of the most poignant expressions of this belief is found in Christian art. In numerous paintings of the angel’s Annunciation to Mary - the moment of Jesus’ conception, the baby Jesus is shown gliding down from heaven on or with a small cross; a visual reminder that the conception brings the promise of salvation through Jesus’ death.

How did December 25 become Christmas?

In the end, we are left with a question. Elements of the festival that developed from the fourth century until modern times may well derive from pagan traditions. Yet, the actual date might really derive more from Judaism - from Jesus’ death at the Passover, and from the rabbinic notion that great things might be expected, again and again, at the same time of the year - than from paganism.

Although the month and date of Jesus’ birth are unknown, the church in the early fourth century fixed the date as December 25. Most Christians celebrate on December 25 in the Gregorian calendar, which has been adopted almost universally in the civil calendars used in countries throughout the world.

For Christians, believing that God came into the world in the form of man to atone for the sins of humanity, rather than knowing Jesus’ exact birth date, is considered to be the primary purpose in celebrating Christmas. The celebratory customs associated in various countries with Christmas have a mix of pre-Christian, Christian, and secular themes and origins.

Concurrent celebrations

Many popular customs associated with Christmas developed independently and include gift giving; completing an Advent calendar or Advent wreath; Christmas music and carolling; viewing a Nativity play; an exchange of Christmas cards; church services; a special meal; and the display of various Christmas decorations, including Christmas trees, Christmas lights, nativity scenes, garlands, wreaths, mistletoe and holly.

The prevailing atmosphere of Christmas has also continually evolved since the holiday’s inception.Celtic winter herbs such as mistletoe and ivy, and the custom of kissing under a mistletoe, are common in modern Christmas celebrations.In Germanic language-speaking areas, numerous elements of modern Christmas folk custom and iconography may have originated from Yule, including the Yule log, the Yule boar, and the Yule goat.

In addition, several closely related and often interchangeable figures, known as Santa Claus, Father Christmas, Saint Nicholas, and Christ kind, are associated with bringing gifts to children during the Christmas season and have their own body of traditions and lore.

Modern history

The Catholic Church promoted the festival in a more religiously oriented form.In 1629, the Anglican poet John Milton penned ‘On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity,’ a poem that has since been read by many during Christmastide. King Charles I of England directed his noblemen to return to their landed estates in midwinter to keep up their old-style Christmas generosity. The book, The Vindication of Christmas (London, 1652), published Old English Christmas traditions.

The revival of the Christmas Carol began with William Sandys’s Christmas Carols Ancient and Modern (1833), with the first appearance in print of The First Noel, I Saw Three Ships and Hark the Herald Angels Sing. In 1843, the first commercial Christmas card was produced by Sir Henry Cole. In 1832, the future Queen Victoria wrote about her delight at having a Christmas tree, hung with lights, ornaments, and presents placed round it. After her marriage to her cousin Prince Albert, by 1841 the custom became more widespread throughout Britain.

In 1843, Charles Dickens wrote the novel A Christmas Carol, which helped revive the ‘spirit of Christmas’ and seasonal merriment. Its instant popularity played a major role in portraying Christmas as a holiday emphasising family, goodwill and compassion. Dickens influenced many aspects of Christmas that are celebrated today such as family gatherings, seasonal food and drink, dancing, and a festive generosity of spirit. A prominent phrase from the tale, “Merry Christmas”, was popularised following the appearance of the story.

In Britain, the Christmas tree was introduced in the early 19th century following the personal union with the Kingdom of Hanover by Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, wife of King George III. An image of the British royal family with their Christmas tree at Windsor Castle created a sensation when it was published in the Illustrated London News in 1848. A modified version of this image was published in the United States in 1850. By the 1870s, putting up a Christmas tree had become common in America.

In America, interest in Christmas had been revived in the 1820s by several short stories by Washington Irving which appear in his The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. and Old Christmas. In 1822, Clement Clarke Moore wrote the poem A Visit From St. Nicholas (popularly known by its first line: Twas the Night Before Christmas).

The poem helped popularise the tradition of exchanging gifts, and seasonal Christmas shopping began to assume economic importance. While the celebration of Christmas was not yet customary in some regions in the U.S., Henry Wadsworth Longfellow detected “a transition state about Christmas here in New England” in 1856.

His Holiness Pope Francis in his latest book, Let Us Dream – The Path to a Better Future explains why we must and how we can make the world safer, fairer, and healthier for all at this Christmas. In the Covid- 19 crisis, the beloved shepherd of over one billion Catholics saw the cruelty and inequity of our society exposed more vividly than ever before.

Pope Francis said that Christians’ first duty is to serve others, especially the poor and the marginalised, just as Jesus did.