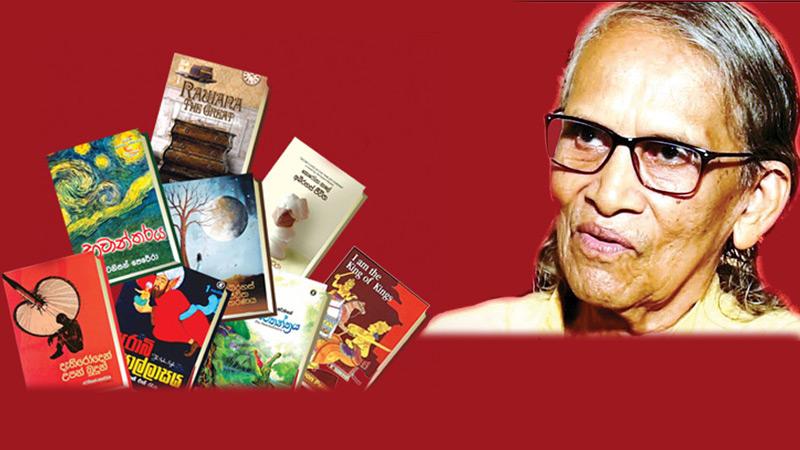

Veteran Sinhala writer Tennyson Perera’s new collection of short stories titled Re Vuna Eli Une Ne (The night without a dawn) is to be launched this month as a Sarasavi bookshop. He also published another collection of short stories last year tit-led Wassane Asuba Horawa (Bad hour of the spring time). Perera has written more than 100 books so far including 31 novels. Apart from writing, he has been acting as a critic and a judge in various literary panels as well. The Sunday Observer spoke to him to discuss his book and his literary life.

Q: You are a prolific writer who writes a few books for a year. How do you introduce your latest short story collection?

A: This book includes nine stories, and through them I tried to experiment with new narrative methods and themes so that go beyond the traditional framework of Sinhala short story. For instance, Malaka Mahima, one story in it, discloses the nature of contradiction in people who seeks spiritual life. Another story deals with drug menace in Sri Lanka, but it explores different aspect of the theme which is of imagination.

Q: You always harshly criticise the Sinhala fiction despising it as a stagnant literature?

A: Though we are boasting about the Sinhala fiction saying it leapt forward during the past decade, I don’t believe it. We see books are being printed, but very rarely, we see good stories. Maybe one or two stories in a book are good, but as a collection they are failed attempts which affirm the fact that we are way behind as a literary tradition. This is why I always try to do a different thing in terms of theme and narrative style in my fiction.

I started to write my new story collection Re Vuna Eli Une Ne (The night without a dawn) to exceed my limitations in the earlier volume. As its title suggests we, as a literary tradition, are at night, we are waiting for dawn, but still there is night.

Q: You reject the story in fiction, but some writers vehemently ask that how can you write a story without a story.

A: Yes, I reject story, but I cannot deny the story of Gabriel Garcia Marquez which accompanies reader to a different world. Fiction of Günter Grass and Haruki Murakami are also like that which are not conventional stories. Those writers do not enrich story, on the contrary, they blast story to break the reality.

Q: How about Dostoyevsky? His fiction is clearly based on a story.

A: Yes, you are correct, but it is an era of the development of fiction.

Q: But you cannot categorise of Dostoevsky’s fiction as underdeveloped.

A: Yes, if you look into Dostoevsky’s fiction, you could see some psychoanalysis in it. Therefore, he doesn’t give just a story to reader, it is beyond that. Look at the fiction of Gogol who was a contemporary of Dostoevsky.

He starts with a story, but at the end of it, he surpasses the story. There, he leaps into magical realism. In my observation, he is the first writer who goes into magical realism. Another great author of this kind is Mikhail Bulgakov who does not remain at the story. He does not write fiction to narrate a story, but to seek answers to his inner mental pressure exerted by political authority.

His novels such as ‘Master and Magarita’, ‘A Heart of the Dog’, attest to this fact. With these examples, you could see that some writers stay at story while others explode story. But I don’t despise Dostoevsky’s fiction, because he gives different perspective and enjoyment to readers through his psychoanalysis. Some critics pointed out that his literature has an existentialistic quality and it is called Dostoevskyan existentialism. In this way, we cannot underestimate his fiction whatsoever.

Q: You have translated two great novels ‘The Castle’ and ‘Judgement’ by France Kafka. How do you see his fiction?

A: Through these novels, Kafka does not relate a story. Though each one has a story, it is way beyond that. He undermines the story in order to display the inner discussion. For instance, in ‘The Judgement’, the protagonist K does not know his judgement in his case, but he revolted against it extensively. Kafka, through this, involves in a huge discussion on court system or rule of law in Czechoslovakia. He does not wish to tell a story there. K in Castle who wanted to become a surveyor also got entangled in a similar situation. The only thing that I don’t like much in K’s life in ‘The Judgement’ is that Kafka makes K’s life tragedy.

Q: Most Sinhala writers, especially women writers in Sri Lanka have been criticising you that you discourage young writers by despising storytelling or story in fiction and promoting exotic magical literature. How do you respond for this?

A: They criticise me because they do not see beyond realism. Sinhala writers and critics are too small to see another horizon in literature. Why does a writer go for magical realism? Because he cannot express himself through realism, as story is not enough for him. Magical realism is an inner discussion of a writer.

Surrealism presents a man inside a man for readers. Surrealism or magical realism is a mirror that put forward in front of readers. Some readers in Sri Lanka are afraid of this mirror. So, they dislike going in front of it in case they see their real image from the mirror.

Q: But one cannot acquire realism or magical realism by force for his or her fiction. Once, Garcia Marquez said that he hadn’t any intention to write his novel ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ through magical realism, he just wrote things he saw in naked eye in his society.

A: But the problem is we, as writers and readers, do not see what is magical realism or surrealism. Once there was a literary discussion at the National Library auditorium, Colombo 7. In that discussion an aspiring writer, among others asked me, “Please explain how to write a novel through surrealism?” The question suggests how much this budding writer is immature. Surrealism is not a form, it’s without form.

You cannot go for surrealistic state by writing in a form. Realism always gives a premeditated form for writer, but surrealism does not provide form for writer. When a writer explodes the realism and reaching into another horizon, he might arrive in surrealism. But for this, a writer has to have a literary obsession. Without the obsession he cannot go into surrealism. Imagination is born by obsession.

Q: But some writers premeditate the story before beginning to write?

A: There are so many wrong notions about fiction writing. One is that an author starts to write with a theme or specific story. For instance, we say that Martin Wickramasinghe started to write Gamperaliya, the first realistic novel in Sinhala, to relate the story of changing the village. But the thing that was actually happened is that Wickramasinghe began to write it just to express himself.

It’s a catharsis experience to him. However, as critics and readers assign him a story saying he embarked into write emergence of middle class. If one begins to write in premeditation, the writing inevitably fails. Premeditation is valid for nonfiction, not valid for fiction. Sinhala literature is filled with these kinds of myths. Writers in it have no courage to go beyond the given feudalism by literary police. They always ready to dance according to beat of the drummer.

Q: But no one has forbidden Sinhala writers from writing in surrealism or any other literary form?

A: I mean the method that we grasp things is totally conventional. We are not looking for new perspective. For a long time, some people in Colombo literary circle despise me as “a magical writer”, but I have never consciously begun to write anything in magical form. When a writer is going on writing, he is just an author.

You cannot dub him so and so. If some magical elements come into his work, it is because of writer’s socio-cultural environment or his upbringing. It comes unconsciously into his work. For instance, Garcia Marquez said that the hens in his village laid gold eggs. The thing that really happened was the hens in his village started to eat gold dusts resulted from gold mining by multinational companies of colonialists. So, it’s his socio-cultural elements that decide Marquez’ art of novel in ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’.

Q: You have been talking about new literature for a few decades. But do you see any magical realistic or surrealistic fiction with high literary value being produced by Sinhala writers?

A: It is very rare such books are produced. Here, I, especially, admire Simon Nawagattegama’s novels and short stories. Then I would like to talk about my fiction. My novel Maha Ravana….

(Disturbed by the interviewer)

Q: Sorry, you cannot judge your own books, because you are the author of them.

A: You are right, but how can I answer your questions?

Q: That’s the point I want to raise. We haven’t produced good literature in the past few decades despite pursuing new literary forms and techniques. So, the reason behind this failure is that we are trying to acquire new styles ignoring our innate forms when writing.

A: It’s one reason for our failure. But there are others. You know surrealism in literature is born mainly due to the development of psychoanalysis by Sigmund Freud. With this psychological viewpoint, we come to understand that every action of a man is controlled by his other man in him. Fantasy in literature is also developed by this perception. So, if a writer couldn’t realise this fact, he never can produce books with these types of ways. This is my idea on this failure.

Q: You are a retired government worker, and you worked at the Government Printing Corporation. And you have vast experience as a striker in Government sector, and you have bad experience as a writer at the beginning. And also, you had to face so many difficulties in your childhood days and recent years. More importantly, you are a product of a Kelani valley area. Why do you use these experiences in your fiction?

A: In some of my books I used them, but generally speaking I consciously avoid my life experiences in writing. I feel I go to backward if I begin to write myself. I prefer to go to imagination rather than recreating my life. But I don’t say that I throw away all my experiences. In fact, I use my experiences to enter the imaginary world of my fiction, but thereafter, I mostly create things, not depend on personal experiences. We have two types of experiences in our life. First, simple experiences, other complex experiences. If we write those simple encounters, it becomes writing like Rosa Male Natuwe Katu, a simple poem in early 20th century by Ananda Rajakaruna. But if we can touch the complex experiences, we could enter into a strange world. I try to pursue this wonderful world when writing. Now I am 81 years old, but still I have been experimenting with myself how to present my fiction productively surpassing realism. Perhaps, I might be the only writer who has been involving in this struggle of modernising the Sinhala fiction. I know people around me devalue my effort, but it doesn’t matter for me.

Q: Don’t you take notice of readers’ and critics’ responses?

A: I don’t belittle them, because a writer resides between reader and critic. But I don’t exclusively depend on them. I don’t like to retreat just because of their rejection.

Q: When all the readers with high-taste and serious critics reject your book, are you still believe that your book is good?

A: Yes, because I don’t know the reason why they reject it. Literary taste is different from one reader to the other. So, I cannot give up my writing style just because of readers or critics.

Q: Don’t you have a literary editor so that you could find your merits and defects?

A: No, I haven’t. I don’t believe in them as well. Editor or critic or any other is behind the author. They cannot overtake author. Editor is good for enhance the content by correcting spellings and grammar errors. But in the West, the editor’s role is different, they interfere even to change the content of a book which I don’t accept.

We know that Salman Rusdie had to face lots of problems including the Fatwa death penalty by Ayatollah Kumeini in Iran, because of his book Satanic Verses. But now, it is revealed that the book was developed into such harsh criticism on the Prophet Muhammad, mainly because of the editors in it. If it were not happened, Rusdie would have been a free man without any death penalty.

Q: You seem to be the sole authority in your fiction?

A: As I said earlier, I do not depend on others in terms of my fiction. I didn’t believe in my wife as well who died three months ago, when editing fiction, because they might worry about the social issues they have to face after publishing the book, the merits in the book are second to them.

Q: To end the interview, I would like to know about the tragedy which you faced recently. How did your house caught fire?

A: A few weeks ago, I started to read IQ84, a novel by Haruki Murakami. You know, it is a big book with more than thousand pages. I first saw this book at Sarasavi Bookshop in Nugegoda. I was so much attracted to it that I read about 300 pages of it in the bookshop. The book deals with the incident Tokyo gas attack which happened some years ago. So, when I took the book home, I began to read it sitting on my armchair at the verandah during the evenings.

One day, while I was reading it, I heard some sounds from inside the house. I thought it was from mongoose which sometimes plays in the house. A few minutes later, I can’t say about the time period exactly, my nose felt a bad burning scent.

I woke up and went inside. Oh no! My house was ablaze by a huge fire. There was no time to think about, I quickly ran outside and cried aloud to the neighbours. People flocked to my house and saved things as much as possible. In fact, my books were saved by them.

At the end of the day, two rooms in the house had caught fire altogether with all my deeds, two almirahs, two desktop computers with printers and drawers full of documents including my Identity card, driving licence and Passport. Though my books in the verandah were saved, I lost many valuable softcopy books in the computer hard disk.

A two hundred-page book of Greek stories, a quarter finished novel and lots of notes for books were among those destroyed. Now, I live in a rented house nearby. I don’t know what to do, because the house cannot be renovated, it has to be demolished and built from the outset. Life is like that. Now I don’t worry about it, anything around us never remains forever. My life goes on despite setbacks. I feel it’s the destiny of a writer.