Beneath the dark vale of sky wherein the Vesak moon was enthroned in her kingdom, a hunter bearing a firearm was wandering in the infinite’ wilderness of Samsara’ hunting its sinful beasts. Under the same cosmic sky, a bhikkhu who seemed to be the exact binary opposite of the sinful hunter, was meditating in the shade of a Bo tree. He was hunting the ‘Minotaurs of sin’ tarrying in the crossroads of his labyrinthine mind.

With the impregnable combination of these two antithetical main characters, a Buddhist intellectual magical realist literature was created in Sri Lanka few decades ago by the legendary sorcerous writer; Siman Nawagaththegama. Beginning from his epic debut; Hunter in the Wilderness of Samsara (Sansararanyaye Dadayakkaraya translated to English by Malinda Seneviratne), the series which extended to the works such as The Story of the hunter (Dadayakkarayage Kathawa), Near the wilderness of Samsara (Sansararanya Asabada) etc, reimagined the civilisational narrative of the natives in the Sri Lankan colony in a much vibrant and magical manner.

Siman’s art of storytelling was often proven to be related to the literary genre of magical realism. Magical realist writers throughout the world could interconnect the mythological concepts, archetypes, supernatural dreams as well as the folklore handed down from generation to generation by the native ancestors in their colonies, with the mundane life they experienced with wide opened eyes, to design a fresh kaleidoscopic literary experience for their readers.

“The Hunter in the Wilderness of Samsara” marks its remarkable beginning with the following words;

“The impenetrable area between our village and Thammannar-Anuradhapura road was covered by thick jungle.”

Cornerstones

The ‘Thammannar-Anuradhapura road’ becomes significant as there lie two cornerstones in the creation of Sri Lankan civilisation. Firstly, the fleet of King Vijaya: first Sri Lankan King with his seven hundred followers had anchored near the golden coast of Thammannar, where Kuweni: the native tribal woman had been weaving the attire of civilisation.

According to the ‘Mahavansa’ historical discourse, Sri Lankans were civilised under a King for the first time with the arrival of Vijaya. Secondly, the ‘Theravada Buddhist discourse’ entered into this island with the arrival of Mihindu Thera, again interconnects with the State power and ideologically invades the mind-sets of Sri Lankans with its dominant religious essence.

Anuradhapura becomes the centre of that religious invasion. It taught us to repress a part of our natural lifestyle considering it as in, and redressed the attires of religious morality for making us the so-called ‘civilised humans’.

Then again, with European colonialism, the fatuous moral laws implemented by queen Victoria for the people in her colonies, made another great ideological impact on the Sri Lankan socio-cultural consciousness.

For example, the same way they; the colonisers impelled the natives to build up a toilet instead of defecating in the forests like beasts, the Victorian morality banned the traditional marital rituals like “polyandry”(Eka Gei Kema), considering them uncivilised sexual behaviour and introduced a nuptial structure limited only for a heterosexual man and a woman. It is the same moral matrimonial structure of the White queen, civilised human beings still carry on our shoulders to the present post-colonial era.

However, the humans who had been subjected to such ideological invasions from time to time, basically civilise themselves through the repression of their primary instincts that control their sexual life. That repression itself is the factor that differentiates humans from the animal kingdom.

Primary instincts

The borderline that separates the two symbols; ‘the forest’ and ‘the civilisation of Mullegama’ found in Siman’s novel explicitly proves the aforesaid idea. Civilisation becomes the residence of civilised human beings. And the beasts wandering in the forest in contrast, become the symbols of their own sins and primary instincts expelled from their civilisation.

The infinite forest imbued eternally with such sinful creatures itself may symbolise the Buddhist concept of ‘Samsara’: the cyclic existence where every sinful creature is endlessly born, dead and reborn. Although the humans endeavour to repress such sinful instincts in their id with morality, from time to time their wild souls would rise up, tearing apart the so called ‘civilised attires’ put on them, and making them afflicted with the wonted animalistic desires.

A fine example for that idea could be found in his novel “Hunter in the Wilderness of Samsara” at the moment three daughters of ‘Lord Mara’: the demonic celestial king of sin in Buddhist literature, return in the middle of the night to break up Hamuduruwo (the bhikkhus’) meditative trance with the erotic caress of their soft fingertips, in the same manner they impeded Siddhartha’s meditative concentration for reaching Buddhahood.

In another part, the readers are encountered with a tiny ant which was believed to be reborn in its previous lives in Samsara as a prostitute, dog as well as the own consort of the bhikkhu, now walking on the face of the bhikkhu tormenting his calm and composed meditative posture. Such mystic ghouls of femininity erratically tormenting the civilisation of men, further remind us of the famous psychoanalyst: Sigmund Freud’s proclamation that “the woman is the indecipherable dark continent never explored completely by the masculine civilisation”.

Antithetical mentalities

In Siman’s novels, we would never be able to witness the clear and complete characters found in conventional realist fictions. Instead, the shades of characters or the characters symbolising the antithetical mentalities of a single individual are often portrayed. Hence, we could also interpret that the dual characters: the hunter and the bhikkhu are not mere separate individuals, but two shades of contrasting mentalities existing within the mind-set of every human being.

The hunter with ‘shabby long hair and a beard’ certainly becomes a symbol of the sinful human consciousness perpetually loitering in the infinite wilderness of Samsara, while the ‘bald’ bhikkhu in the Mullegama temple represents the opposite: the wisdom and Nirvana: the quenched human soul with no suffering, desire or sense of self. The concept of ‘hair’ is often portrayed in Buddhist literature as a metaphor for sin, as even prince Siddhartha believed to have cut off his own long hair before leaving the sinful paradise of his palace in search of Nirvana.

But, as Siman himself reveals that this hunter was the patriarchal guardian of the forest and the bhikkhu, and neither the hunter nor the forest in return could exist without the bhikkhu, the writer highlights the great philosophical idea that no light, merit or a quenched soul could exist in this world without their opposites: darkness or sin.

Those binary opposite characteristics are always intricately bounded with each other like the two sides of the same coin. They don’t have an intrinsic existence devoid of each other. Every creature and incident in this wilderness of Samsara is also essentially interconnected with each other like a macrocosmic spider web. It is the basic idea of “Shunyata” brought by the Mahayana Buddhist philosophy.

Symbols of lust

According to Friedrich Nietzsche, “A tree that would grow to heaven must send its roots to hell.” In “The hunter in the Wilderness of Samsara” we encounter such a holy Bo tree with its branches and roots extended simultaneously towards heaven and hell. Though the Bo trees are considered an utmost holy symbol in the modern ‘Victorian-Buddhist’s’ belief system, the ancient Indians had even mated with their partners ritually under the shades of Bo trees expecting childbirths, thus making them even the symbols of lust.

These opposing characteristics possessed by such archetypal trees are even explicitly manifested in the movie Leopard Do Not Bite (Sansare Dadayakkaraya) directed by Prasanna Vithanage with the inspiration of Siman’s sorcerous literature, as the final frames of it show the image of a colossal Bo tree with its roots structured like the naked human carvings endlessly bounded with each other by lust, found in the ancient Indian temples of Konark, Kajuraho and Halebeedu.

In “The Story Of the Hunter”, the hunter confronts a spiritual deity in the forest who ultimately mates with him, impelling him to steal a bunch of male seeds from the demonic king living in the great ‘Asoka tree’. Just like the Bo trees, Banyan as well as such ‘Asoka’ trees too become the symbols of lust as according to historical allusions, Asokamala the low caste village woman believed to have magically enchanted prince Saliya; the son of the great King Dutugemunu, in a forest of Asoka trees in the region of Inamaluwa near Sigiriya.

The writer throughout his sorcerous literary works, depicts the wild soul of the Eastern woman expelled from the masculine civilisation built this way. The hunter for instance, amid all the strange phantomic females he encounters in the forest such as the deities and Naga Manavika (Cobra women) also begins to hear the lugubrious lamentation of Kuweni; the first woman banished from this civilisation by King Vijaya, condemning herself as a demoness with three breasts. Such mythical allusions even remind us of the wise European women who were burned alive by the hegemonic patriarchal power of the Church in history condemning them as the witches with three breasts.

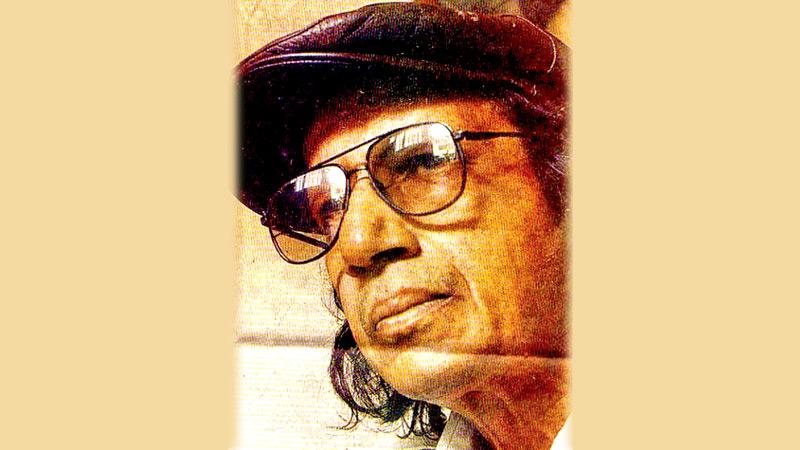

In this way, this sorcerous hunter in oversised glasses and long Bohemian hair: Siman Nawagaththegama, redesigns his 82-year-old wilderness of Samsara, magically reinterpreting every narrative of our civilisation hidden within its depths.