It was in 2013 that I paid my first visit to No. 24, Lester James Peries Mawatha. I was a law student at the time, but was freelancing on the arts to a newspaper.

I have the vaguest recollection of that first visit, but I do remember that it lasted barely 15 minutes. The Perieses were expecting a visit from some relatives abroad: I would have to come another day.

The second visit transpired around two weeks later. I have the vaguest recollection of that too, but I do remember conversing with Lester for three hours. Or was it four? In any case, “Mrs Peries” chipped in only halfway through.

As Ambassador to France |

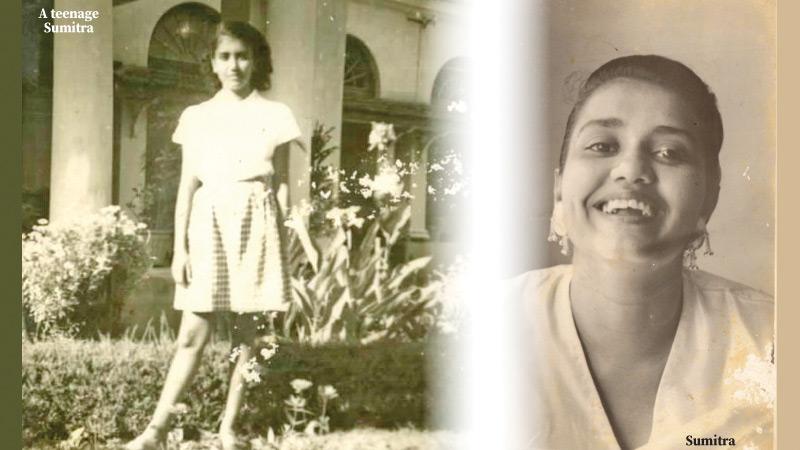

Over time the visits became more regular and frequent, marred by the occasional, inevitable disruption. My conversations would always be about Lester, his work, his conception of the cinema, and the people he had met. Sumitra, in all this, remained aloof.

Soon the visits came to include lunch and, occasionally, tea. It was at these lunches that I began talking more with Sumitra. Though I sensed a reluctance to open up, she became increasingly amenable to talking with me about her work. It helped that the first Sinhala film I had seen, and liked, was Sagara Jalaya (1988). I had been only 10 at the time.

Interlocutor

Dr. Peries’s health began to deteriorate soon after, and as a result my visits became shorter and more infrequent. Sumitra would act as his interlocutor for me, adding to what he said and correcting him. After a while, she began talking about herself, her views on the cinema, and the people she had met in her long career. After a point, Dr. Peries became too weak to entertain any more visits. It was then that I really started interacting with her.

Be it a physical visit, a social function, or a phone call, Sumitra and I wound up talking to each other about the interests that enthralled me as a cultural critic. The phone calls alone would last beyond an hour, sometimes two; at one point we stopped at the two-and-a-half-hour mark.

Though she never wrote and hardly ever spoke in front of an audience, she was a cultural gadfly, her interests ranging across so many fields.

She was fond of talking about two things: her brother Gamini (or Kuru) and her friendship with Lindsay Anderson. We talked about films too. If the conversation was about the latter, she would, somehow, always return to Carl Theodor Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928) and Renée Falconetti’s magnificent performance. “That film,” she told me,”did more to push me into directing than any other work.”

There were also films she did not take to, especially the violent ones. One of her most vivid memories here was Lester’s obsession with Pulp Fiction (1994), a film she did not regard highly. The two of them had been in Paris then, during her tenure as Ambassador. “I never really understood why Lester liked it,” she pondered with me.

After Lester passed away in 2018, No. 24 became the centre of a huge legal wrangle. There were calls for Sumitra to leave. These could not be avoided. Eventually, a house was located for her at Mirihana, a suburb she happily found to her liking.

The Perieses had a very large library, featuring a great many rare titles. Working with a team of GCE A. Level students from the Royal College Hostel who admired her, I catalogued them.

We hoped to move them all to her new house. But for some reason, many of them were taken to the Colombo Public Library. Although the Library made assurances that they would return to her the books she wanted, she received no word from them.

Soon we resumed contact, and I began visiting her again. Though these were not her best months and years, her situation gradually improved.

Shooting her films |

The Japanese Government conferred the Order of the Rising Sun on her in 2020. Then Britain and Germany evinced an interest in screening her films, particularly Gehenu Lamayi (1978). Among the people who contacted her in this regard was Mark Cousins, whose passion for film preservation and restoration, and whose interest in Sumitra’s work, was admirable to say the least.

Force to reckon with

More than anything, I think this showed that Sumitra had been a force to reckon with in the regional, even world cinema, and that the world had not lost its interest in her. I wish I could say the same of her own country’s officials.

As her relatives and acquaintances will attest, none of the relevant local institutions committed themselves enough to promoting her films in these countries. Far from facilitating their screening, she and her associates had to put up with an immense cobweb of bureaucratic red tape from them.

Over the years, and through these encounters, Mrs Peries – she became Dr. Mrs Peries last year –became a mentor, a guide, and an advisor to me.

There are very few people I have encountered who have never, not even once, exuded that arrogance and sure-footedness which comes with honours and titles. Neither Lester nor Sumitra were arrogant in that respect. Indeed, Lester was fond of telling me that he exhibited his arrogance through his humility.

This made them eminently approachable. And in fact, so many did approach them, seeking their advice, their direction. It was always generously given.

Sumitra’s loss is the nation’s loss. This is a clichéd way of putting it, but it’s true. “An end of an era,” a mentor of mine and a distant relative of hers messaged me from Toronto. Again, clichéd but true.

There’s no denying that the country has lost one of its last cultural icons and international figures. My grief, however, is more personal. I’ve lost one of my mentors and gurus. In my case, as in the country’s, that space can never be filled.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at [email protected]