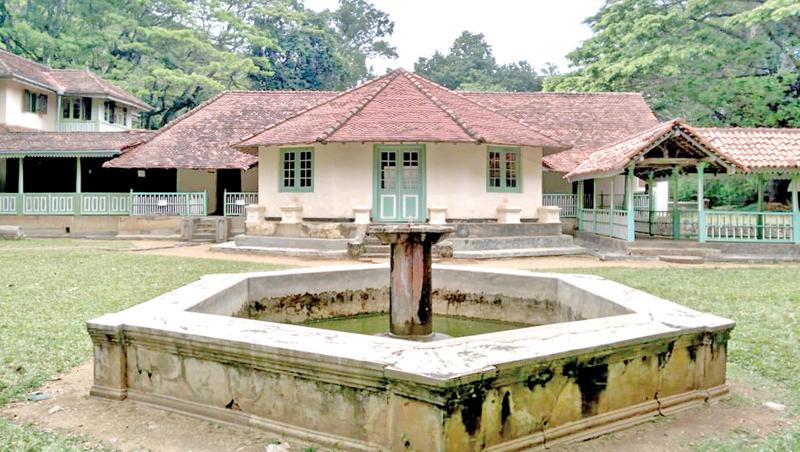

The Archaeology Department officials who accosted us at the Maduwanwela Walawwa in Kolonne last year showed us the Delft tiles at the entrance and pointed us to a likeness of Queen Victoria near the inner courtyard, and suggested that these revealed the Dissave’s resistance to colonialism.

It seemed difficult to come to another conclusion. Who, after all, would want to express his admiration for a person or an idea by stepping on it, especially at his residence? Besides, the Dissave had built a reputation for haughtiness and arrogance, and for his short height, and he built his manor in such a way that, regardless of their rank, visitors would have to bend before entering or meeting him.

The evidence, then, pointed clearly in one direction. The Dissave had been a fervent anti-colonialist if not anti-imperialist, and despite the high offices he had received from officials he had taken every opportunity to rub it in their faces, so to speak. But then something seemed odd. Towards the end of our tour, we came across a portrait of the Dissave. Stately and majestic, despite his short height, his name lay inscribed underneath.

This caught us unawares. Not only had he adopted a Christian and Anglicised name – James Williams – but he had also received a knighthood. How could one reconcile his anti-imperialist credentials with his acceptance of these symbols of fealty to the Crown? On our way out my friend tried to resolve this paradox: “They didn’t care much about his placing a portrait of Victoria on the floor and felt it much easier to bribe him with titles.”

Anti-colonial streak

My friend had almost proposed a solution. But it sounded inadequate to me. His rationale was that colonial authorities tolerated if not overlooked the Dissave’s dismissive attitude to these desiderata and contented themselves in granting him tracts of lands, and conferring titles on him, in the hopes of coopting him. Having read through a hagiographical account of the Dissave and his family back home, however, I knew this could not suffice.

My friend had almost proposed a solution. But it sounded inadequate to me. His rationale was that colonial authorities tolerated if not overlooked the Dissave’s dismissive attitude to these desiderata and contented themselves in granting him tracts of lands, and conferring titles on him, in the hopes of coopting him. Having read through a hagiographical account of the Dissave and his family back home, however, I knew this could not suffice.

The answer, after much reflection, seemed more straightforward to me, thought it may sound heretical to some. My argument is that his attitude to those desiderata was not dismissive at all, but was instead symbolic of his attachment to such symbols, and his acceptance of the ideology underpinning them. In other words, the Dissave’s anti-colonial streak was a ruse, a distortion of the historical reality, revisionist, and hence utterly false.

In the temples of the Southern Province – which borders on Kolonne, through Embilipitiya and Urubokke – one discerns a similar contradiction: a bust of Victoria at the entrance, and carefully placed Delft tiles in the ambulatory. The Head Priest at the Randombe Vihara in Ambalangoda gave us not one but two explanations for this paradox: regarding the portrait of Victoria, he argued that people had wished to pay tribute to the sovereign under whom they had been able to establish the temple, and regarding the Delft tiles, he suggested that those same people had wished to express their opposition to colonial rule by symbolically treading on them. Having travelled through these temples, I am certain that other monks, from other Vihares, would propose the same rationale and solution: that on the one hand people wished to commend Victoria and on the other they wished to oppose colonialism. Note the paradox here: they accept the person, but oppose the ideology underpinning his – or in this case her – subjugation of their country, their way of life.

Acceptance of colonialism

Anthropologists and art historians may seek complex solutions for these paradoxes, but in this case, as in many others, the simplest answer is the most tenable. As with the placing of the Delft tiles and Victoria’s likeness at the Maduwanwela Walawwa, these do not underlie opposition to but rather acceptance of colonialism. It is difficult to say whether locals would have been discerning, or to be more accurate dim-witted, enough to distinguish between the physical embodiment and the ideology of colonialism, or between Victoria and Victorian England.

Personally, I think it is an insult to their intelligence to think they harboured two contrasting attitudes to the reality of imperial rule. The same goes for the Dissave: given the titles and lands he obtained from the British State in recognition of his loyalty to the Crown, it is utterly anachronistic to paint him as a critic of colonialism.

Unlike the temples of the Kandyan kingdom, the temples of the South were patronised by elites no different in their attitude to imperialism than the Dissave.

That is why, as I pointed out last week, it would be somewhat ridiculous to think, or to suggest, that these elites, who poured their newfound wealth on these temples and on their palatial residences, would seek to subvert colonial rule, even through symbolism.

As Sena Thoradeniya noted in an implied critique of an earlier article I wrote on this issue, to argue that placing Delft tiles on your floor reveals your anti-colonialism would be to suggest that the manufactures of those tiles were anti-colonial as well.

Opposition vs loyalty

But then, someone can counterargue, what of the Dissave’s decision to place a likeness of Victoria on the floor? The most logical answer to that came to me during an interview with Ravindra Randeniya, who plays Ehelepola Adigar in Prasanna Vithanage’s Gaadi. Reflecting on Maduwanwela and on his own ancestors, Randeniya remembered how, in the early 20th century, practically every family owned a portrait of the British sovereign, and how these portraits would be hung “almost everywhere”, to symbolise not just their attachment to but also their affirmation of British rule. If that sounds somewhat odd, consider that not even the most fervently nationalist from this period could envisage a Ceylon falling outside of the British orbit.

Nationalist agitators were critical of British rule, but they were careful also to rationalise their opposition to the worst excesses of British rule in terms of overall loyalty to the British Crown. Indeed, their campaign for rights for their communities was articulated as a means of cultivating more loyalty to the British sovereign.

Given all this, the mystery of Maduwanwela no longer becomes a mystery. No one likes a colonialist in their family, and the aim of revisionist histories may well be to conceal their imperialist heritage. It is in this light that we must read contemporary accounts of colonial elites, and it is against this backdrop that we must critically scrutinise such accounts, even if they are echoed by officials tasked with preserving the country’s heritage. Reality, after all, is not just stranger, but also simpler, than fiction.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at [email protected].