Aug 23: The Channel Tunnel linking Britain and France holds the record for the longest undersea tunnel in the world – 50km (31 miles) long. More than 20 years after its opening, it carries more than 10 million passengers a year – and more than 1.6 million lorries – via its rail-based shuttle service.

What many people don’t know, however, is that when owner Eurotunnel won the contract to build its undersea connection, the firm was obliged to come up with plans for a second Channel Tunnel… by the year 2000. Although those plans were published the same year, the tunnel still has not gone ahead.

The second ‘Chunnel’ isn’t the only underwater tunnel to remain a possibility. For centuries, there have been discussions about other potential tunnelling projects around the British Isles, too.

These include a link between the island of Orkney and the Scottish mainland, a tunnel between the Republic of Ireland and Wales and one between Northern Ireland and Scotland.

Some of these tunnels yet may happen: even the Channel Tunnel built for the railway in the 1980s was the culmination of nearly 200 years of thought and discussion.

At the time, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s own preference was for a road tunnel, not the current railway service. She liked the idea, some believe, because cars “represented freedom and individualism”.

But Thatcher’s project was considered unsafe, says Eurotunnel spokesman John Keefe. It’s one thing to send trains through the tunnel at wide intervals; it’s quite another to allow hundreds of drivers through in an endless stream.

Should a crash or pile-up occur 15 miles out to sea, it would be very hard to rescue those trapped in the chaos.

“It was considered not the right thing to do, even though Margaret Thatcher pushed very hard for it,” says Keefe.

The prime minister compromised. “She said, ‘All right, I’ll go along with the safety argument, I’ll accept that, but as technology improves I want a commitment to plan a second tunnel – a road tunnel’,” Keefe adds, paraphrasing. Even when the plans were made and released more than 20 years after the prime minister’s demand, they were still considered too risky. But that might change.

One of the major problems – noxious fumes from hundreds of vehicles – will become less of an issue with the rise of hybrid and electric cars, says Keefe. Safety, too, may be a more minor concern, because autonomous driving technology already allows some experimental cars to pilot themselves along motorways. They could theoretically do the same in an undersea tunnel, potentially reducing the chances of a crash or jam.

If technology does evolve in these ways, then plans for a second tunnel could be revived. “I think it’s highly likely that conversations like this will take place in the coming 10 or 20 years,” Keefe says.

Alan Stevens at the UK’s Transport Research Laboratory agrees. He suggests that by the 2030s technology may have reached a critical point.

“You’d have to say only automated vehicles of a certain standard, and ones that could move together – then you’d get a nice flow through your tube,” he says. “It’s certainly something that I think will be thought about.”

Tunnel vision

The first meaningful attempt to build a tunnel across the English Channel happened much earlier than most people think.

In 1880, a century before the modern project got underway in 1988, work started on experimental tunnels at the base of Abbot’s Cliff near Folkestone. Creating an undersea connection with France across the English Channel was something that had been talked about since the early 1800s, and supporters included Napoleon Bonaparte.

In some places, the men worked with hand tools. But they also had an ingenious contraption with them – a tunnel boring machine. As compressed air in the machine’s motor forced the rotary head into action, tough rock in front would fall away.

Keefe is one of relatively few people today to have visited the site. Deep inside the warren, the aging tubes carved out by the boring machine are mostly featureless, though there is one piece of Victorian graffiti scratched into the rock: “THIS TUNNEL WAS BEGUNUG N [sic] in 1880” – signed “WILLIAM SHARP”.

“They look like you imagine an old Cornish tin mine to look like,” says Keefe, describing the place. “They’re low wooden [beams], pretty intact and pretty dry. But they are nothing like what you really need to run an international undersea tunnel.”

The venture was typically ambitious for the time, says Graeme Bickerdike, rail engineer and editor of engineering history website Forgotten Relics. “Nothing seemed to faze the Victorians,” he says. “They had a vision of the transformational nature of railways and they clearly saw a link to the continent being critical to that vision.”

But it was not to be. Beyond the technical challenges, there were political fears about building a direct connection to a country with which Great Britain had so frequently been at war. Sir Edward Watkin, who was in charge of the excavations, at one point suggested that in the event of conflict the entrance to the tunnel could be collapsed with a mine wired to a button somewhere – perhaps even as far away as London.

Tunnel fever is still with us. Recently, the idea of a Welsh-Irish link was mulled in a 2014 document by the Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport (Cilt).

The report argued that by 2035, such a connection could be a “serious topic of debate”. But the proposal has “not gone much further since”, says Andrew Potter, who chairs Cilt’s Cymru-Wales committee. Part of the problem is that it would be an exceptionally long connection – at 100km (62 miles) or so it would be roughly twice the length of the Channel Tunnel. Further north from there, a much shorter distance – between 10 and 25km (6 to 15 miles) – exists between various coastal points in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

That’s short enough to build a bridge across, though the cost would certainly amount to a few billion pounds. Still, that hasn’t stopped the idea of a tunnel or bridge being mooted by politicians in both countries in recent years.

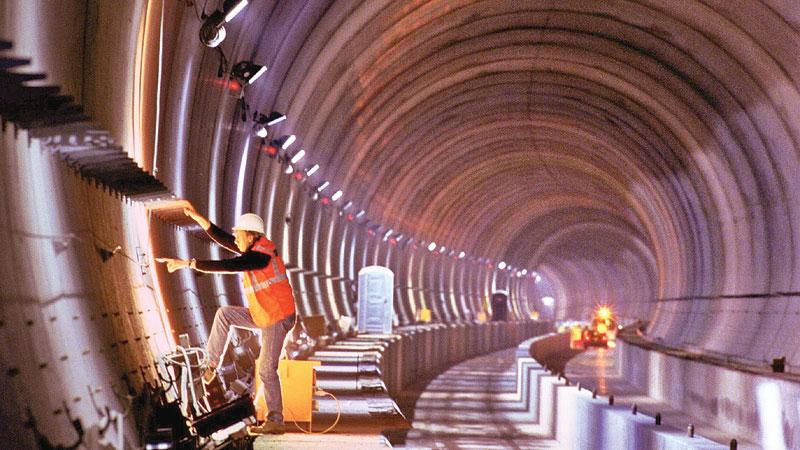

In the meantime, British tunnelling expertise is being put to good use elsewhere. The most obvious example is London’s Crossrail, which is the largest civil construction project in Europe.

A smaller but significant project will soon follow – the Lower Thames Crossing will connect Essex and Kent, in part via a new tunnel under the River Thames.

And further afield, British engineers are also assisting with the development of another major venture: the Fehmarn Belt Fixed Link. Linking the Danish island of Lolland with the German island of Fehmarn, the tunnel will feature an 18km (11 mile) undersea portion. Construction is due to start as early as the end of 2017.

Richard Miller of engineering consultancy Ramboll UK, which is Danish-owned, explains that the tunnel will be pre-fabricated on land, floated out to position and then lowered into a trench on the seabed. This is known as an immersed tube, or IMT, design and has been used before, including for the Sydney Harbour Tunnel in Australia.

“The casting is on land, so there’s no construction in the ground in dirty wet holes,” says Miller. The Channel Tunnel and Crossrail’s tunnels, by contrast, were created using a cylindrical tunnel boring machine (TBM).

Pipe dreams

The Channel Tunnel came in at £4.65bn (£8.5bn, or $11bn, today) and the Fehmarn Belt Fixed Link will probably cost more than 7bn euros ($8.2bn).

That hasn’t stopped some dreaming, though. Take Elon Musk’s Hyperloop – a proposed, ultra-fast mode of transport in which pods lifted by magnetic levitation are propelled along tubes. If it ever becomes commercially viable, some have wondered whether it could one day link Europe and the United States with a gigantic tube spanning the Atlantic Ocean.

“Some of the really interesting tunnels they’re looking at now are variations of floating tunnels, so the tunnel isn’t on the seabed, it’s floating within the water body,” says Miller.

That might make a trans-Atlantic connection a little more feasible, but there would still be extreme costs involved and, of course, safety issues. How to evacuate passengers if a pod stalls half-way between continents?

John Keefe can’t resist pondering the notion, though. “What a brilliant, brilliant idea,” he says. But he acknowledges the huge hurdles any such design would face.

Even so, perhaps there is reason to be hopeful.

“Our tunnel was a dream for 200 years,” he says. “Maybe 200 years ago, the channel looked as big a challenge to Napoleon’s engineers as crossing the Atlantic does today.”

- BBC.com