Packing ‘The Wendt’ to ‘ full house’ capacity is no cake walk. Many a stage play, have I watched where not even one third of the seats at the Wendt were occupied. This is especially so when it comes to Sinhala theatre. Rajitha Dissanayake, one of the most well known names in contemporary Sinhala theatre is a practitioner whose works, when staged at the Wendt, draw theatregoers from varied strata to achieve a practically full house. I have seen that repeatedly over recent years, and Saturday November 10 was no exception, when yours truly sat in the gentle darkness of the Lionel Wendt auditorium to witness Dissanayake’s latest play to the Sri Lankan stage -‘Hithala Gaththa Theeranayak’- which carries its title in English as ‘A well thought out decision’.

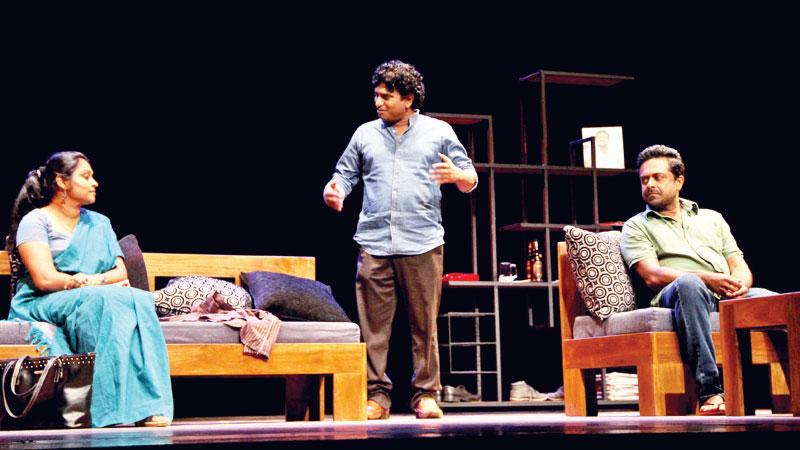

The crux of the play revolves around a matter that is of significant concern in present day Sri Lankan society, which is, ‘divorce’. Bound to the context of this subject of spousal estrangement and its debates is the matter of love and honesty. How much of each, and ‘both’ are necessary to make a marriage work? And to that effect what is the definition of a ‘functioning marriage’? At the core of ‘Hithala Gaththa Theeranayak’ are those questions set within the story of an average middle class Sri Lankan family where the husband, played by veteran actor of the stage and screen Shyam Fernando, develops what he honestly declares to be a deep and true feeling of love for a young colleague at work, and this ‘unfaithfulness’ is discovered by his wife, played by Samadhi Laksiri. The result is the breakdown of the institution called ‘marriage’.

The crux of the play revolves around a matter that is of significant concern in present day Sri Lankan society, which is, ‘divorce’. Bound to the context of this subject of spousal estrangement and its debates is the matter of love and honesty. How much of each, and ‘both’ are necessary to make a marriage work? And to that effect what is the definition of a ‘functioning marriage’? At the core of ‘Hithala Gaththa Theeranayak’ are those questions set within the story of an average middle class Sri Lankan family where the husband, played by veteran actor of the stage and screen Shyam Fernando, develops what he honestly declares to be a deep and true feeling of love for a young colleague at work, and this ‘unfaithfulness’ is discovered by his wife, played by Samadhi Laksiri. The result is the breakdown of the institution called ‘marriage’.

This is a story about how people fall in and out of love and how ‘love’ can have different meanings in differing degrees to the partners in a relationship. The action flows in a way where one may even ask, are there lasting ‘partnerships’ in relationships or is it simply a form of ‘participation’? Gives one food for thought I dare say. Can someone be a participant in a relationship? In the manner of being a participant at an event or a competition? Dissanayake’s play goes into these matters not in the most overt manner but in unobtrusive indications as the action plays out on stage and one is left to ponder over it in retrospect.

In matters of divorce the ones who suffer the most are said to be the children, (if there are any in the picture). Curiously enough Dissanayake doesn’t quite literally bring the married couple’s two children into the ‘scene’ but makes reference to them.

There is no visible plight of the children brought out in this play. It is thus a play about adults, meant (mainly I presume) for adults and those who are at the threshold of adulthood not so much in terms of crossing over to the legal age of maturity but the responsibility of entering into commitments that bind one to another in ‘conjugal oneness’.

The play shows early on the mercurial way in which the wife’s love for her husband turns to hate to the extent of wishing him dead giving pulse to the words of English playwright and poet William Congreve who has written in his play ‘The Mourning Bride’ – “Heav’n has no rage like love to hatred turn’d / Nor Hell a fury, like a woman scorn’d.”. And it is perhaps worth noting that an interpreted turn of phrase of Congreve’s line as ‘Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned’ is often misattributed to William Shakespeare.

Fernando’s character in a soliloquy, breaking the fourth wall, asks his audience whether it is right for a woman to wish the man who is father to her children to be dead simply for having said ‘I love you’ to another woman? What makes Fernando’s character one who can win the sympathy of an audience is his genuineness of being true about how he feels. The tragedy that he encounters is partly because he is open to his own disconcerting discovery that he cannot or at least should not lie about how he feels ‘love’ for another woman.

He is in that sense a man who unintentionally invites tragedy into his life simply because of his idealistic notion that the beauty of what he believes to be love, should not be sullied with the falsehood of denial simply for ‘marital survival’. I cannot help but feel that in this lead male character Dissanayake offers a character that contains a vein of the famous advice from Polonius to his son Laertes in Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet’ – ‘To thine own self be true, as night follows day.’

In a bid to show that she too can embark on an affair and to prove that she can still attract the ‘affections’ of a man of ‘significance’ Laksiri’s character shows a woman who is bent on settling the score simply to show her own ‘worth’ to the man who wronged her. Well made decisions are therefore consequently underway and the estrangement reaches its point of no return.

Presented with stagecraft that is typical of Dissanayake’s style, which I might describe as perhaps quasi realist cum halfway minimalism, the play unfolds in two principal spaces –the household of the family that falls apart, and the train station.

Logistically therefore it has been designed for portability as well, I dare say. (In that one can see the craftsmanship of Dissanayake, whose works are created to reach audiences in different corners of the country).

It is an unpretentious work of theatre that tells a straightforward story with five characters. It is not of a didactic interior, neither of an aesthetically splendorous exterior, nor of a profound philosophising foundation. Its simplicity is its virtue to win over its viewers as a story performed on the boards for the general Sri Lankan theatregoers, who appreciate a story performed by a skilled group of artistes, set in the times we live in and the issues that beleaguer us. Needless to say with ‘Hithala Gaththa Theeranayak’ Dissanayake will again renew his fidelity to his established audience, the mainstream Sinhala theatregoers across the country.